“Traditionally, the girl’s parents pay for the wedding,” my then-fiancé noted as we drove away from a store where he had used my Visa to buy something for himself. I had good credit. He didn’t. This purchase was added to an embarrassingly large tab I had extended to him since we’d been together. He promised to pay it back, and I felt I had to believe him. By that point, it was almost enough to pay for a wedding.

“I feel really cheated,” he told me.

My father had died two years earlier, leaving me a modest inheritance which my fiancé quickly depleted. The fact that I now was unequipped to fund a wedding was one of the increasingly frequent complaints he had about a ceremony he supposedly wanted. He couldn’t decide on whether he wanted to exchange vows in front of 40 or 150 guests, or whether we should celebrate at a restaurant, barn, city hall or experimental art space. Whenever I brought up the wedding, he told me it wasn’t a good time to talk. He was busy throwing other parties that I wasn’t invited to. Sometimes, I wondered if I would be invited to my own wedding.

"My father died, you spent my inheritance, and you feel cheated?” is what I didn’t say to him that day. Instead, I kept driving, and allowed myself for the first time to consider getting out. Ann Patchett once described her broken relationship as train she could no longer imagine jumping off. Patchett married her mistake. I decided to jump off.

When I first met him, he drove an Accord and dressed like a tenured English professor. He was in the middle of reading Absalom! Absalom! and he promised to make me his mother’s paella. He spent his weekends driving back and forth to Philadelphia to take care of his grandparents. By the time he dumped the Honda for a used Corvette and a Members Only jacket, and I figured out that he was never going to make me paella, I was already on the train. When he proposed on a sidewalk during a thunderstorm—his soggy idea of romance, not mine—I thought the declaration could help resolve my cognitive dissonance. I thought, “he does love me.” I thought, “maybe this is as good as it gets.” Way in the back of my head, I thought, “There’s always divorce.”

When I finally found the courage to break off the engagement a few months later, I discovered that I was not the only one who had been circling around those same thoughts. Friends and family responded to the news with carefully-chosen words like, “elated,” “about time,” and “thank God.” I had dreaded telling them, not because I was afraid they wouldn’t understand, but because I would have to explain why it took me so long to wake up. After months of giving opinions about color schemes while “watching me stand in the path of a slow steam roller,” I was worried I had exhausted my support system.

They weren’t exhausted. They wanted to party. Some were polite about concealing their delight; others broke out the noisemakers. I was told that I deserved a float. Candy. Clowns. A parade.

For the first time, I considered the idea that my social obligations to my cancelled engagement were not over. Was I expected to do something on the day I was supposed to get married? When I pictured broken engagements, I saw distraught brides in pre-paid Vera Wang gowns, scooping peanut butter out of the jar with their fingers. I imagined grooms cowering in a dingy bar, plugging the jukebox with quarters to play another Morrissey song. I thought it was something you suffered in private, like an STD.

Weddings have become such a mega-monster event in the United States—the average one costs more than $20,000 and ropes in accomplices from the furthest reaches of your social networks—it seems appropriate to offer some kind of shadow event, an anti-matter to balance out the Bridezillas and Bridalplasty. I’m horrified by a lot of wedding traditions, with their strict cohesion to outdated gender roles. But at least they offer a blueprint to survive the day, even if you choose to adapt or reject many of them. The day that you intended to get married isn’t defined by an event, but by its absence. There is no etiquette to follow or betray.

Real Simple’s Wedding issue offers no advice on commemorating a near-miss. Even Hollywood doesn’t give much direction here. True, romantic comedies seem designed as inspirational texts for leaving your fiancé at the altar: Have Tom Selleck punch him in the face, and marry him instead; break a conspicuous seashell necklace to reveal your evil fiancé’s true self; trick a family into thinking you are engaged to their son, and confess your well-meaning sins at the altar. These films all give us an idea of how to jump off the train, but have no practical advice when you finally land on the ground. They all drift off at the exact moment things get complicated. Do you keep the dress? Who takes the lease? Should you still talk to your mutual friend you knew first, but who speaks to him more? And who do you have to sleep with in order to close your account at The Knot?

Though there isn’t a Hallmark card (or even a Someecard!) to commemorate the occasion, I was far from the only one who wanted to celebrate what a friend called my Nearly Beloved Day. Almost everyone I knew had a friend, coworker, or once-removed cousin who hadn’t gone through with a wedding, and they were eager to tell me how they spent the day. Seeing a broken wedding date come and go, I discovered, was almost as normal as pulling one off. And how a bride-not-to-be marks the day hinges, as you might expect, on whether you were the dumper or dumpee, and how soon before the train station you decided to leap off.

Soon, I found that the people I had most invested in my wedding were eager to help me call it off in style. One of my intended bridesmaids, Alison, was on her second cancelled wedding as a member of the bridal party. She pointed me to Lisa, a non-gambling elementary school teacher, who went to Atlantic City to celebrate her Nearly Beloved Day. Financially wiped out by non-refundable deposits, Lisa and her friends smuggled a 30-pack of Miller Lite into their purses and drank in seedy casino bathrooms. Lisa instructed me to talk to Dana, but I can’t—when she called off her wedding, she went to India to pray. No one knows when she is coming back. And it’s not just for the ladies. John didn’t want to celebrate his Nearly Beloved Day, but friends convinced him to drink some microbrews on the Annapolis Bay, and he was glad he did.

Jean, an almost-bridesmaid who was never particularly fond of her friend’s prospective groom, was “elated” when the bride called the wedding off. On the day the wedding wasn’t, Jean showed up in Chicago—plane tickets and dress already paid for—armed with a white “maid of honor” baseball cap and her floor-length, key-lime bridesmaid’s dress. She and the bride spent the weekend at Lake Geneva crashing the Chicago Fireman's convention, drinking, sunning, and trying on fireproof trousers.

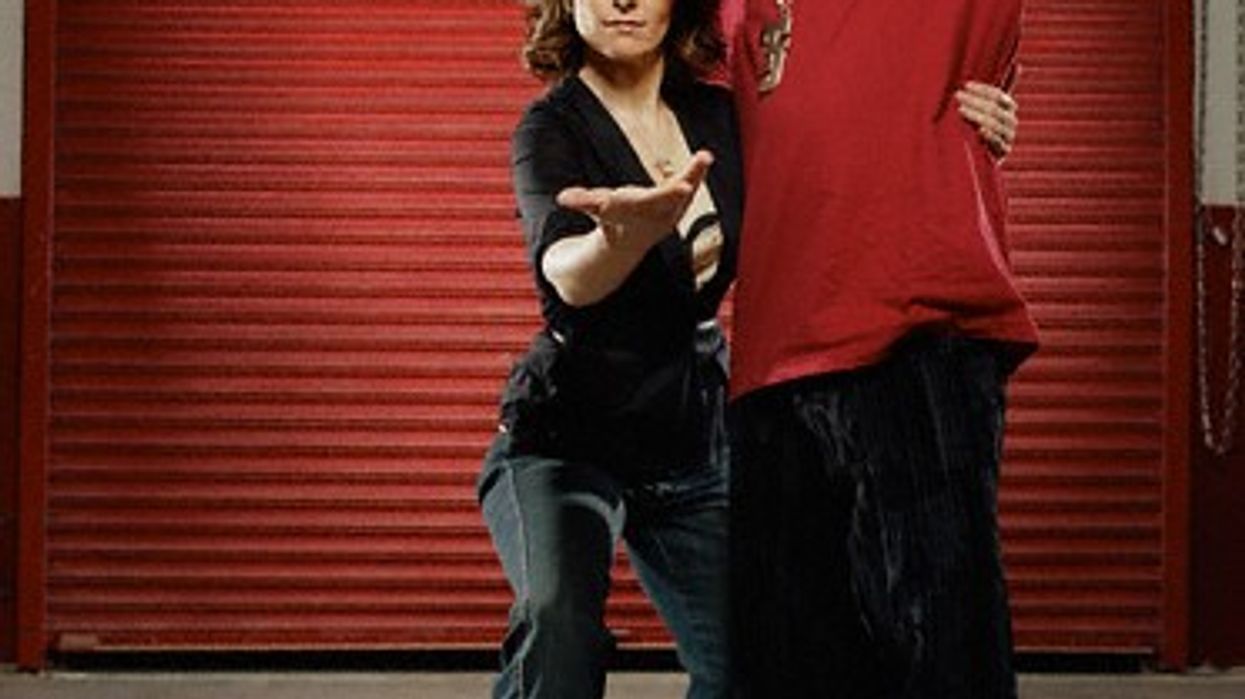

Everyone had an opinion about what I should do. Henri, who plans high-concept parties for a living, wanted me to host extreme leisure games involving close calls, like Dodgeball or limbo. Seth went to one of those parties once where the wedding dress hung on the wall like a crucifix. Kathleen suggested I talk to her sister who has been engaged seven times to see how an expert handles the logistics. It could be worse, Abbey told me—she had a co-worker who had thrown herself an “annivorcery” every year for the past ten years to mark the day her divorce was final. Abbey has not been brave enough to go. Mike went to one that a bride threw for herself, and there was cake. Do not have a cake, he cautioned.

By the time my Nearly Beloved Day arrived, I didn’t really need a party. I was in a new relationship with a very tall man who I could only sheepishly describe to people as “like, just really, really good,” and I was more interested in charting out the future than marking the past. But my friends had just lost me to the weight of an unhealthy relationship and helped me pull myself out from underneath it. The party was for all of us—we could now return to our previously scheduled friendship.

So my Nearly Beloved Day was a group production. One friend designed the invitations, another put down his credit card to cover the deposit for the restaurant, and a third conspired to fly in a surprise guest. One friend, who calls herself an art clown and normally refuses to perform at parties, even put on a squishy pink nose and a wig. I wore a pink chiffon vintage dress with mint green heels, gave countless hugs, and never had to order my own drink. We partied more in the back room of that restaurant than we would have at the cancelled wedding. The really, really good guy held my hand the whole time, just as he would a few years later when we walked down the aisle together. When it was time to make a toast, we didn’t celebrate close calls. We drank to the relationships we’ve had all along.