No one seems to want to admit when American water isn't safe to drink. Instead, they try to hide it.For years, U.S. health officials have claimed that although the drinking water at North Carolina's Camp Lejeune is contaminated, it poses no danger to Marines or their families. This April, the government reversed itself, saying that its assessment of the water contained "omissions" and "inaccuracies," and adding that a million people over the course of three decades may have been exposed to the carcinogen benzene in their water. Fifteen hundred former Lejeune Marines, some of whom are now afflicted with rare lymphomas, have filed lawsuits seeking more than $33 billion. Sadly, Lejeune is just one of the many recent poisoned-water cover-ups in American history. There are others going on all the time. Here are some more of the worst.

Location Brooklyn, New YorkYears 1800s to 1950sIn the largest petroleum spill in American history-three times bigger than the one caused by the Exxon Valdez-between 17 and 30 million gallons of oil and waste were gradually dumped from Brooklyn's once-bustling refineries into Newtown Creek, an estuary dividing Brooklyn from Queens. In the decades since, the spill has seeped into the groundwater and now gurgles under a 55-acre swath of the Greenpoint neighborhood. While the area's drinking water comes from distant reservoirs, benzene-laced sludge is slowly making its way to the surface. The cleanup remains only half complete.Location Niagara Falls, New YorkYears 1950s to 1970sWhy would Hooker Chemical sell the charming Love Canal neighborhood to the city of Niagara Falls for just $1? Perhaps because Hooker had used the canal as a dumping site for 20,000 tons of its waste. When the city built low-income housing and a school on the buried canal and its surrounding land, it failed to warn citizens about the mountain of poison beneath them. Soon, children were coming home with chemical burns, women passed poison on to their children through breast milk, and neurological problems and cancer rates rose sharply. In 1979, the EPA called the town's miscarriage rate "disturbingly high." Eventually forced to intervene, the federal government relocated all 800 Love Canal families.Location Woburn, MassachusettsYears 1964 to 1979In the mid-1970s, when children in East Woburn began dying of leukemia at unusually high rates, parents correctly feared tainted groundwater. Since the 1960s, workers at a W. R. Grace & Co. Cryovac food-packaging facility had been dumping waste trichloroethylene, a toxic solvent, onto the ground behind the plant. And Beatrice Foods, which owned a local tannery, was storing 55-gallon drums of waste near the Aberjona River. Seven families sued, and a notoriously loopy trial (documented in the book A Civil Action) saw Beatrice acquitted and Grace fined only $8 million, most of which went to legal fees.Location Hinkley, CaliforniaYears 1970s to 1980sA small town near natural-gas pipelines in the middle of the Mojave Desert, Hinkley was the perfect place for one of Pacific Gas and Electric's compressor stations. The company began storing cooling-tower water in unlined ponds, assuring residents that the hexavalent chromium added to the water to prevent rust was safe for consumption. But when the chromium leached into the groundwater, Hinkley citizens began experiencing a number of ailments, including cancers and birth defects. In 1993, with the help of a legal clerk named Erin Brockovich, the townspeople sued and won $333 million in damages.Location Washington, D.C.Years 2001 to 2004Washington's Water and Sewage Authority became aware that dangerous amounts of lead had seeped into the city's drinking water. The water authority hid its findings until a 2004 Washington Post article exposed the elevated lead levels. Along with many others, a father of twin boys exposed to the contaminated water is now suing the WASA for $200 million, alleging that problems associated with his sons' lead poisoning costs his family upwards of $40,000 per year.

Location Brooklyn, New YorkYears 1800s to 1950sIn the largest petroleum spill in American history-three times bigger than the one caused by the Exxon Valdez-between 17 and 30 million gallons of oil and waste were gradually dumped from Brooklyn's once-bustling refineries into Newtown Creek, an estuary dividing Brooklyn from Queens. In the decades since, the spill has seeped into the groundwater and now gurgles under a 55-acre swath of the Greenpoint neighborhood. While the area's drinking water comes from distant reservoirs, benzene-laced sludge is slowly making its way to the surface. The cleanup remains only half complete.Location Niagara Falls, New YorkYears 1950s to 1970sWhy would Hooker Chemical sell the charming Love Canal neighborhood to the city of Niagara Falls for just $1? Perhaps because Hooker had used the canal as a dumping site for 20,000 tons of its waste. When the city built low-income housing and a school on the buried canal and its surrounding land, it failed to warn citizens about the mountain of poison beneath them. Soon, children were coming home with chemical burns, women passed poison on to their children through breast milk, and neurological problems and cancer rates rose sharply. In 1979, the EPA called the town's miscarriage rate "disturbingly high." Eventually forced to intervene, the federal government relocated all 800 Love Canal families.Location Woburn, MassachusettsYears 1964 to 1979In the mid-1970s, when children in East Woburn began dying of leukemia at unusually high rates, parents correctly feared tainted groundwater. Since the 1960s, workers at a W. R. Grace & Co. Cryovac food-packaging facility had been dumping waste trichloroethylene, a toxic solvent, onto the ground behind the plant. And Beatrice Foods, which owned a local tannery, was storing 55-gallon drums of waste near the Aberjona River. Seven families sued, and a notoriously loopy trial (documented in the book A Civil Action) saw Beatrice acquitted and Grace fined only $8 million, most of which went to legal fees.Location Hinkley, CaliforniaYears 1970s to 1980sA small town near natural-gas pipelines in the middle of the Mojave Desert, Hinkley was the perfect place for one of Pacific Gas and Electric's compressor stations. The company began storing cooling-tower water in unlined ponds, assuring residents that the hexavalent chromium added to the water to prevent rust was safe for consumption. But when the chromium leached into the groundwater, Hinkley citizens began experiencing a number of ailments, including cancers and birth defects. In 1993, with the help of a legal clerk named Erin Brockovich, the townspeople sued and won $333 million in damages.Location Washington, D.C.Years 2001 to 2004Washington's Water and Sewage Authority became aware that dangerous amounts of lead had seeped into the city's drinking water. The water authority hid its findings until a 2004 Washington Post article exposed the elevated lead levels. Along with many others, a father of twin boys exposed to the contaminated water is now suing the WASA for $200 million, alleging that problems associated with his sons' lead poisoning costs his family upwards of $40,000 per year.

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

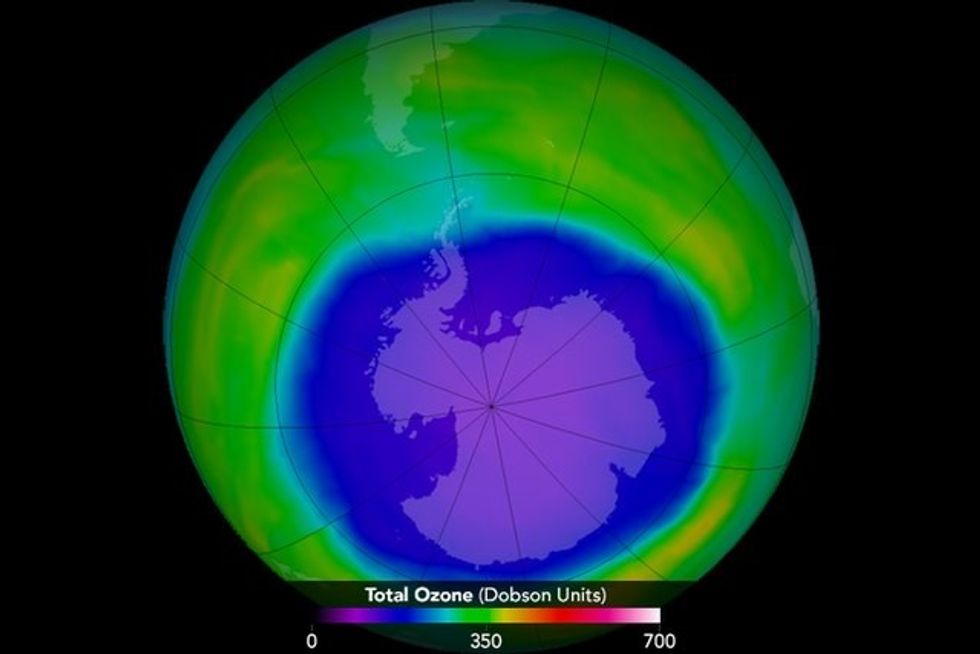

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva

In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva

Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva

Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva

Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.