Search

Latest Stories

Start your day right!

Get latest updates and insights delivered to your inbox.

We have a small favor to ask of you

Facebook is critical to our success and we could use your help. It will only take a few clicks on your device. But it would mean the world to us.

Here’s the link . Once there, hit the Follow button. Hit the Follow button again and choose Favorites. That’s it!

The Latest

Most Popular

Sign Up for

The Daily GOOD!

Get our free newsletter delivered to your inbox

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

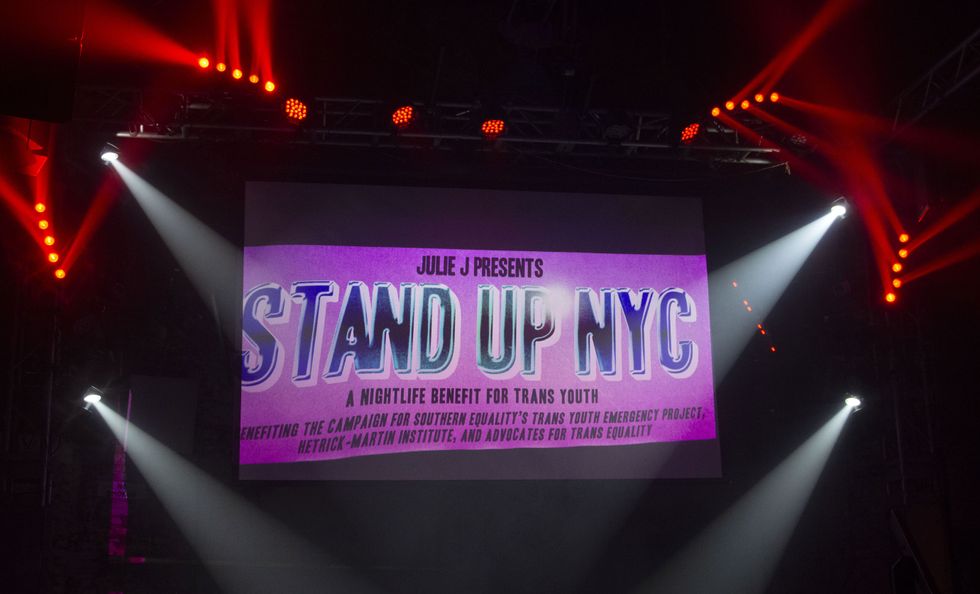

On March 30, Julie J gets organized in the DJ booth before Stand Up NYC begins at 3 Dollar Bill in Brooklyn. Elyssa Goodman

On March 30, Julie J gets organized in the DJ booth before Stand Up NYC begins at 3 Dollar Bill in Brooklyn. Elyssa Goodman Julie J in the DJ booth. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J in the DJ booth. Elyssa Goodman Julie J poses for pictures prior to the show's start. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J poses for pictures prior to the show's start. Elyssa Goodman Julie J at 3 Dollar Bill before Stand Up NYC begins.Elyssa Goodman

Julie J at 3 Dollar Bill before Stand Up NYC begins.Elyssa Goodman Julie J on stage co-hosting Stand Up NYC. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J on stage co-hosting Stand Up NYC. Elyssa Goodman