When New Yorker Stacy Berman was young, she would take MDMA (otherwise known as “molly” or “ecstacy”) once in awhile for recreational reasons. It just made her feel good, she says. So when she discovered as an adult that she’d been suffering from Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD)—often found in victims of child abuse and Holocaust survivors—she thought she’d give MDMA another try.

At the time, Berman was working to complete a doctoral program in mind/body medicine. She couldn’t believe how much MDMA helped. “The idea behind CPTSD is that in a situation where a person is not able to fight or flee, they tend to freeze up… MDMA allowed me to start feeling again,” she says.

[quote position="right" is_quote="false"]It’s difficult to set up and run clinical trials on MDMA because it’s a Schedule 1 illegal substance, like heroin.[/quote]

Researchers have been studying this party drug for years now, digging up compelling physiological and behavioral evidence that MDMA promotes strong feelings of empathy, closeness, and positivity. The substance is scientifically classified as an “empathogen” and was described by The Daily Beast as a “turbo-charged SSRI” (or antidepressant).

Over the years, the results have been so intriguing to leading Stanford neuroscientist/psychiatrist Robert Malenka and his colleague Boris Heifets, an anesthesiologist, that the two teamed up to argue that MDMA is worthy of rigorous scientific exploration. Their commentary appeared late last month in the journal Cell.

“For many decades both in my own work and as a well-trained neuroscientist, I've viewed psychoactive substances as valuable probes of the nervous system,” says Malenka. He’s especially fascinated by how MDMA evokes what he calls “a powerful pro-social effect.” In other words, it appears to promote “positive, good feelings towards another member of your species, rather than negative, aggressive feelings,” he says.

But it’s difficult to set up and run clinical trials on MDMA because it’s a Schedule 1 illegal substance, like heroin. The National Institute on Drug Abuse states that high doses of MDMA “can lead to a spike in body temperature that can occasionally result in liver, kidney, or heart failure or even death.” Overdoses and deaths at raves or festivals like 2013’s Electric Zoo shouldn’t be ignored. Still, Malenka and Heifets argue, trials on the safety and utility of MDMA have uncovered undeniable therapeutic potential. Notably, a 2011 controlled study of a group of PTSD sufferers published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that 83 percent of the participants who received MDMA no longer qualified as having PTSD by its end. Another study from 2016 showed that MDMA reduces social anxiety in autistic adults.

Before MDMA can be effectively utilized as a form of therapy, Malenka says its molecular underpinnings need to be better understood. Early research has suggested that MDMA may influence the release of the neurochemical oxytocin, the hormone essential to feelings of love and bonding in humans. But, says Malenka, “What hasn't been done is really trying to figure out which of those molecular targets are the most important for its pro-social effects—where in the brain those molecular targets are located.”

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]One controlled study of PTSD sufferers found that 83 percent of the participants who received MDMA no longer qualified as having PTSD by its end.[/quote]

This is where the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Study (MAPS) comes in. Malenka credits the organization with having done a tremendous amount of work in raising awareness and lifting legislative and legal burdens to study MDMA. According to their website, “MAPS is undertaking a roughly $20 million plan to make MDMA into a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved prescription medicine by 2021.”

Compass, which is pushing for similar goals but primarily for psilocybin (mushrooms), also focuses on “accelerating access to evidence-led innovation in mental health and well-being,” according to its co-founder and director George Goldsmith.

Goldsmith is optimistic about the future of hallucinogenic-based drug therapies. “We think there could be great promise in combining these medicines to create a greater sense of openness with a new therapy in a careful, supportive environment,” he says, adding that they have no intention of eventually pushing these kinds of drugs “at CVS or Walgreens.”

Berman, who went on to finish her doctoral program and found her own integrated wellness startup, agrees. After taking MDMA an estimated six or seven more times over a five-year period—in combination with therapy and meditation—Berman feels that it allowed her to “open up and feel vulnerable again and trust people.” Her encounter with MDMA’s therapeutic purposes inspired her to more deeply research what was behind the “profound feelings of love and connection” she’d experienced. After looking into a number of studies, Berman feels confident stating that the MDMA “literally rewired my brain in a way that allowed me to start feeling and then to process the good and the bad.”

Of course, Berman recommends caution and care when pursuing this illicit substance, both because it is illegal and because she feels anyone intending to take it must “always know and trust the person who has given it to you. Be in a safe environment.”

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Shake It Off Wet Dog GIF by BuzzFeed

Shake It Off Wet Dog GIF by BuzzFeed

Working out with friends also makes exercise more enjoyable (and feel quicker).Photo credit: Canva

Working out with friends also makes exercise more enjoyable (and feel quicker).Photo credit: Canva

People with Imposter Syndrome can't accept their achievements.

Photo by

People with Imposter Syndrome can't accept their achievements.

Photo by  Emotion Feeling GIF by Quilt

Emotion Feeling GIF by Quilt Psychologist - Free of Charge Creative Commons Notepad 1 image

Psychologist - Free of Charge Creative Commons Notepad 1 image

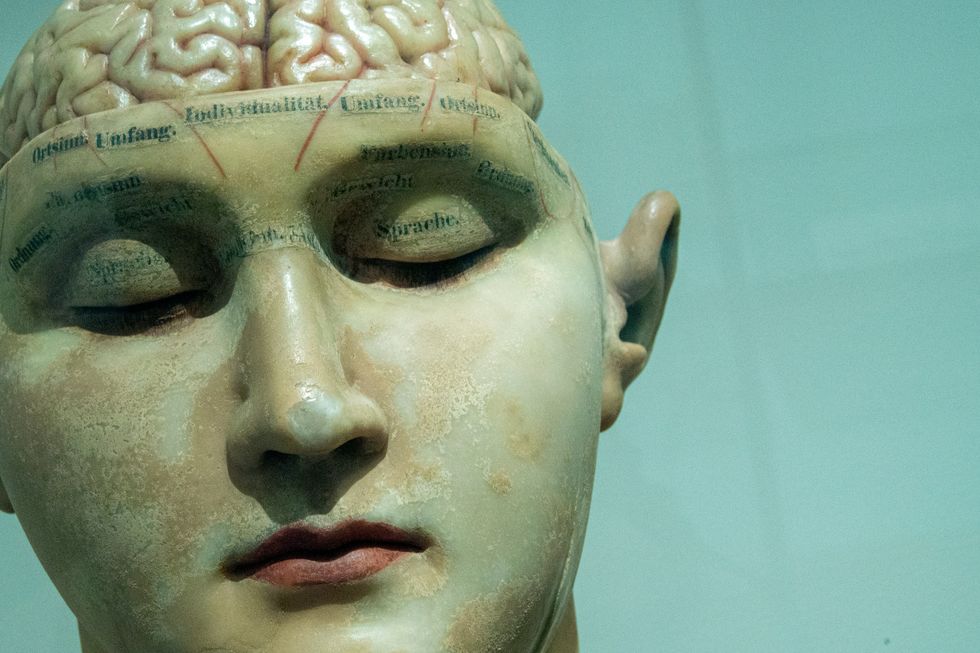

Human anatomy model.

Photo by

Human anatomy model.

Photo by

Socks warm your feet, but cool your core body temperature.Photo credit: Canva

Socks warm your feet, but cool your core body temperature.Photo credit: Canva

A new t-shirt could open up more hospital beds for patients.Photo credit: Canva

A new t-shirt could open up more hospital beds for patients.Photo credit: Canva Wearable solutions could be revolutionary.Photo credit: Canva

Wearable solutions could be revolutionary.Photo credit: Canva Many wearable tech devices could help you monitor your health.Photo credit: Canva

Many wearable tech devices could help you monitor your health.Photo credit: Canva