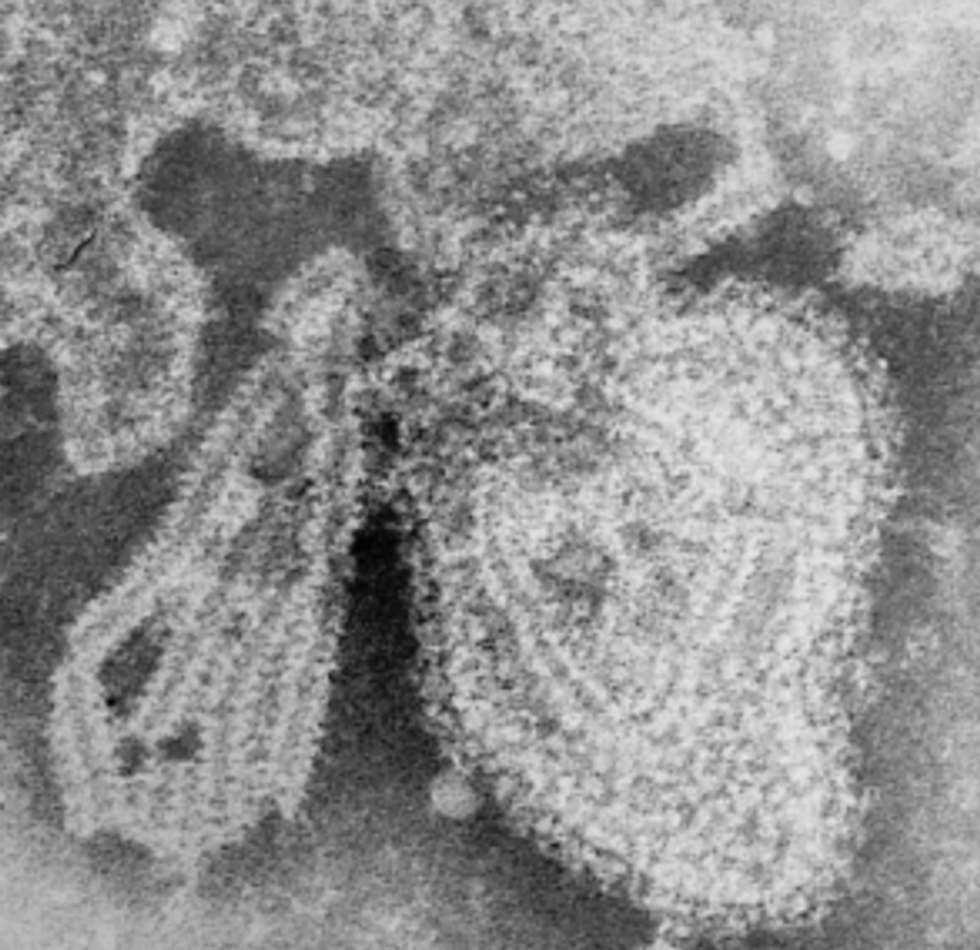

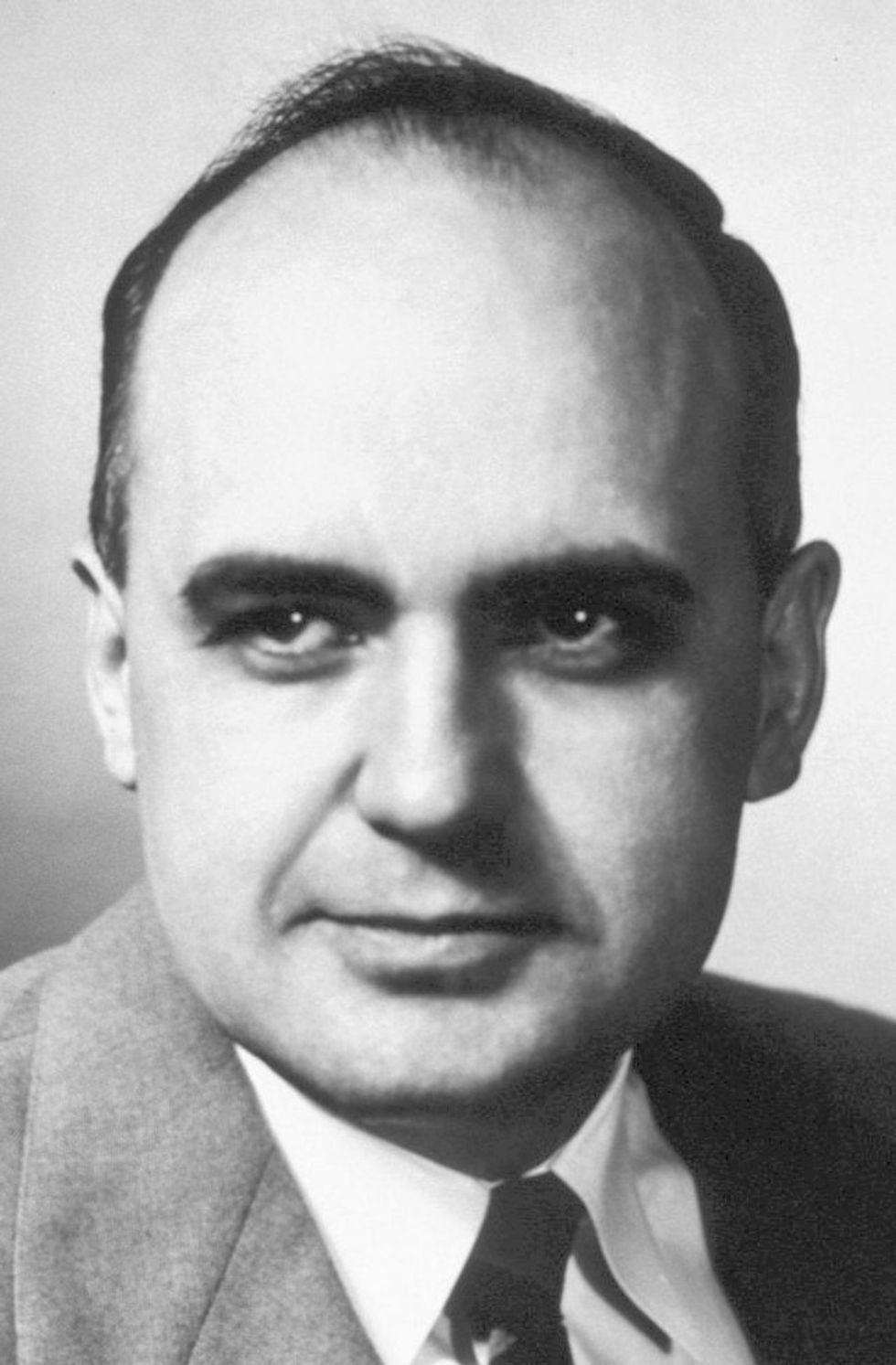

In 1963, Dr. Maurice Hilleman’s daughter, Jeryl Lynn, was sick. She was infected with MuV, a very contagious virus that causes swelling and inflammation of various glands and body parts. If left untreated could possibly cause deafness, pancreatitis, and, in rare cases, sterility. Using his training and experience, Hilleman rubbed a cotton swab in his own child’s throat to isolate the MuV to see if he could discover a way for others to develop an immunity to this damaging viral disease. He succeeded. Jeryl Lynn recovered on her own, fortunately, but would comfort her baby sister, Kirsten, in 1966 when her father administered a shot of the preventative treatment.

In 1967, Hilleman’s treatment was approved and widely recommended by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Thanks to this treatment, infections of MuV in the United States went from an average of 162,000 cases per year in the 20th century down to only 429 cases recorded in 2023. Hilleman’s work has saved and preserved the health of millions over the last 50-plus years. In fact, the now-called “Jeryl Lynn strain” of the treatment is still being used today. The treatment was a vaccine, recommended to be given to babies and young children. You likely heard of MuV by its more common name: the mumps.

This wasn’t Hilleman’s first time encountering and creating a vaccine. Hilleman isn’t just known for the mumps vaccine, but is widely considered in the medical community as a pioneer in modern vaccination and microbiology. After growing up during the Great Depression, Hilleman studied and was able to get his PhD in microbiology through various scholarships, graduating in 1944. Starting his work amidst the conflicts during World War II, Hilleman developed a vaccine for Japanese B encephalitis, which was desperately needed for soldiers fighting in the Pacific front. In 1957, Hilleman was recruited by the private sector, accepting a position at Merck & Company. From then through the 1990s, Hilleman and his team created more than 40 different vaccines. This includes vaccines currently being used to protect against mumps, measles, chickenpox, rubella, pneumococcal pneumonia, meningitis, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, chlamydia, and pandemic influenza.

Hilleman’s body of work alongside his science partners have saved an estimated 150 million children from fatal diseases over the past 50 years. They’re part of the reason why infant mortality has improved globally, from around 10% in 1974 to less than 3% in 2024.

Developing the mumps vaccine seems like a daunting task and ask, but in the end the motivation was simple and relatable. A father saw that his child was sick and just didn’t want anyone else to suffer like she did. This dad just used the know-how and skills he had learned, earned, or was given to help. This dad just happened to be a microbiologist and vaccinologist that was called to act.

You likely aren’t a microbiologist, but you don’t have to be one to make a difference to many. If your kid needs a playground to run around in and you’re a carpenter, ask your community if you could help build one in the neighborhood for everyone to enjoy. If your local library has closed, set up a small “take-a-book, leave-a-book” shelf by your mailbox. It may seem small, but it could still make a big difference in the day-to-day lives of those around you. Just ask yourself what your abilities are and keep your eyes open for opportunities to use them.

The military used Henry Johnson for recruitment efforts.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The military used Henry Johnson for recruitment efforts.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Cheers to the regulars!Photo credit: @emilymichele28

Cheers to the regulars!Photo credit: @emilymichele28 Being a regular could benefit your life in several ways.Photo credit: Canva

Being a regular could benefit your life in several ways.Photo credit: Canva