There’s a famous line in the 1962 film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, where a matter of historical fact goes awry, that says “when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” There are numerous cases where this happens throughout history. As The Huntington research library shares, “We build collective memories of our history to pass on to future generations and make the stories fit who we think we are or who we want to be.”

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

A myth that came to be known as history arrived two decades prior to the American Revolution. As the story goes, Lydia Chapin Taft was the widow of wealthy landowner Josiah Taft. Josiah Taft had passed away after the death of his college-aged son, Caleb. Josiah had been involved in the local government, but upon his passing, his wife was given the right to vote at a town meeting on October 30, 1756. The subject of the vote that day was said to be a potential allocation of funds to the French and Indian War. With Lydia’s vote, the allocation was said to have passed. She was said to have voted in two more of the town’s meetings later on. To commemorate Lydia’s achievement as the first woman voter, a highway, route 146A in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, where the vote took place, was named in her honor in 2004.

These details were chronicled by Judge Henry Chapin, a descendant, in an 1864 speech. But as researcher Jocelyn Sears noted in a 2015 article for Mental Floss, there’s actually no historical documentation of whether or not Lydia voted in those instances, or ever. “According to records from Uxbridge’s town meetings, there wasn’t any meeting on October 30, 1756, and the town did not appropriate any funds that year for the war or for unspecified colonial purposes,” Sears wrote. “Further, even if Lydia Taft had voted, we’d have no way of knowing, since the official minutes for the town meetings do not list the names of people voting or their votes.”

Still, this doesn’t mean Taft’s actions never happened, per se. A scholar local to Mendon, in Worcester County, Massachusetts where Lydia was born, told the Mendon Free Press newspaper it’s possible discussion of Lydia’s voting record arose from “a conversation where she informally influenced the outcome, later to be described as a vote.”

The recounting of a tale like Lydia’s is not uncommon throughout history. “Sometimes those stories from the past are not historically accurate because our memories don’t quite hold on that long,” The Huntington Library astutely observes. “Over time those accounts can become stories and myths that we tell each other about what happened, and those stories shape our identities as a nation.”

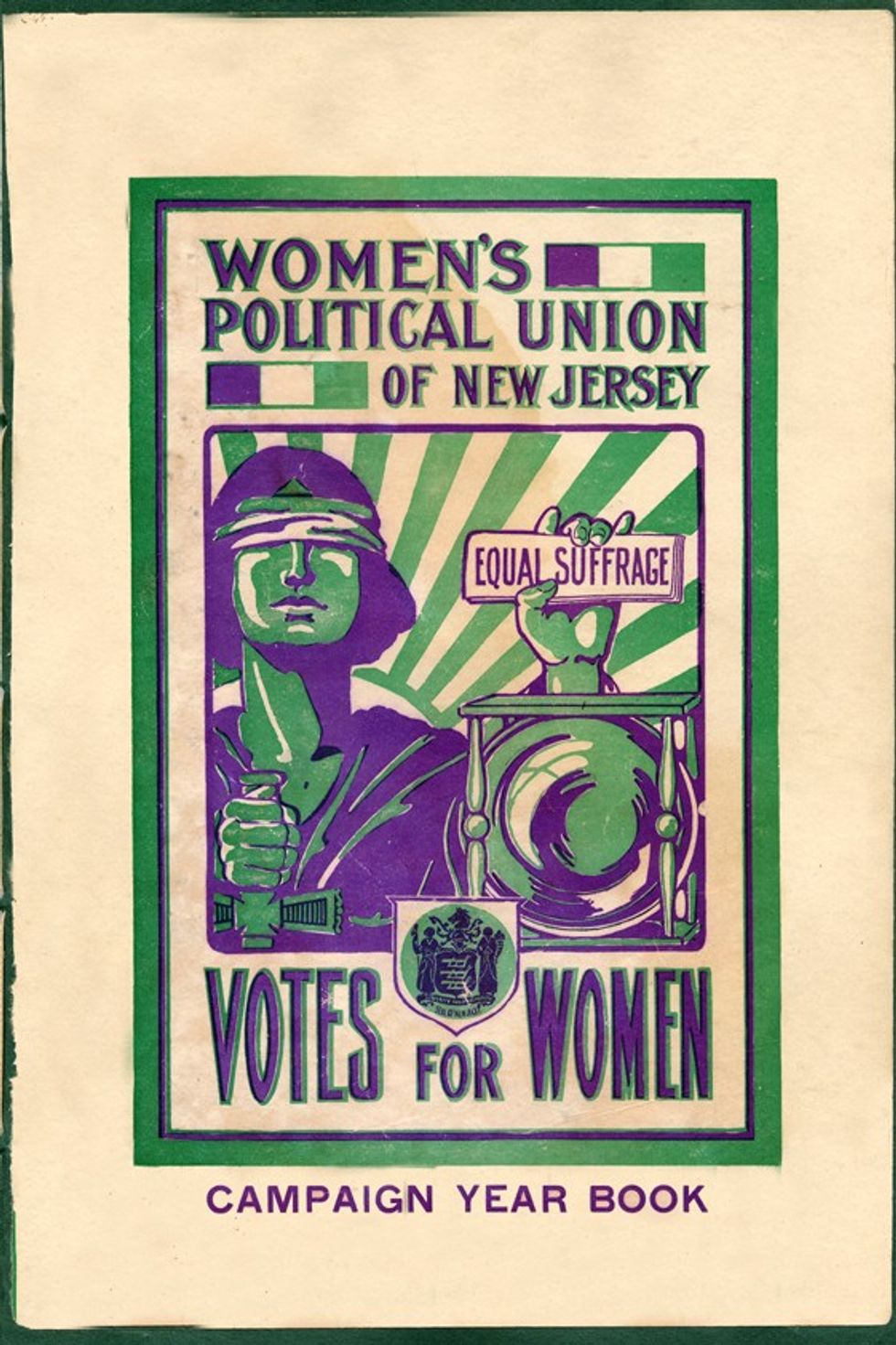

And while much more documentation is needed than exists to prove Lydia’s story was real, there was actually a moment where women were able to vote long before the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. In New Jersey, women were able to vote between 1776 and 1807. “The 1776 New Jersey State Constitution referred to voters as ‘they,’ and statutes passed in 1790 and 1797 defined voters as ‘he or she,’” the Museum of the American Revolution shares. “This opened the electorate to free property owners, Black and white, male and female, in New Jersey. This lasted until 1807, when a new state law said only white men could vote.”

Similarly, historian and scholar Dr. Shirley Buchanan shared in an interview with the Historic Hawaii Foundation that while prior to the 1893 Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom “the concept of the ‘vote’ by western standards is perhaps too narrow to apply to Hawaiʻi in the nineteenth century,” noble women in the Kingdom of Hawaii, aliʻi women, “certainly carried on their right to ‘vote’ or create and implement legislation. Women who were not aliʻi [makaʻāinana, or commoners] could appeal to the government directly as is evidenced by petitions.” Queen Liliʻuokalani was among these great ali'i, and became the leader of Hawaii's ‘Onipa‘a, or "steadfast," movement, fighting against American annexation. Though she was ultimately dethroned, her legacy and fight for Hawaii's rights lives on.

As we move toward the end of Women’s History Month, there are still many proven yet undertold stories about America’s progressive past; indeed, if anything, it reminds us of the need for such a month to begin with.

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: