While you might use a social media wall post to humble-brag about your new iPhone, share a baby pic or, admit it, an LOLcat, 19 year-old Lynisha is using her Camellia Network profile page to raise her son right, get a GED and overcome dire odds.

Lynisha is a former foster child.

The Camellia Network is a new nonprofit social network designed to help Lynisha transition from foster child, to thriving adult. The site taps several current trends of tech and media to tackle a perennial if overlooked problem in the back corner of the child welfare world: what happens to foster kids when they stop being foster kids? They still have all the emotional baggage from an abusive past. They still don't have a family, a support network, and often don't have an income or other resources once they leave state protection.

Enter thousands of strangers on the internet to help fill the void where loving parents should be. Money helps for sure, but this project is showing that put to the right use, a wall post on a teen’s profile page can open the door to a better life.

It’s hard enough to leave home for college for middle class teens. But for the nearly 30,000 foster kids who are thrust into adulthood each year, the transition to grown-up can be a tumultuously critical time. When a foster child turns 18 or 21 (different states have different caps) they lose the protections of the state system and get booted out of their homes, often with no support or resources to help set up life as an adult.

A quarter of kids who age out end up homeless within two years or incarcerated, according to figures provided by the Camellia Network. Sixty percent of them have children of their own, who are then twice as likely to end up in foster care themselves.

“It’s this horrible cyclical pattern that, I think, a lot of people aren’t aware of,” says Isis Keigwin CEO and Co-Founder of the Camellia Network, launched in September.

Thus the cycle continues, argues Keigwin and her co-founder Vanessa Diffenbaugh, author of “The Language of Flowers,” inspired by her own experience as a foster child. In the actual language of flowers, Keigwin explains, a Camellia signifies “my destiny is in your hands,” thus the name of the social network the pair created to break that cycle.

“Companies are using technology to solve all of their problems, but there’s so little happening with [technology] in child welfare,” says Keigwin.

The most direct aid the network provides is financial. Her site lets these disadvantaged youths set up a basic needs registry—something like a wedding registry for things like a bathmat or diapers. The participants choose from pre-approved items available on Amazon and then share their wishlist with the world.

Nineteen year-old ViQuan’s entire registry of 26 items was fulfilled: there was a $24 desk; $10 pie pans; a few spatulas; three small rugs; and the most expensive item, an $85 blue luggage set.

As you’d expect, there’s absolutely nothing lavish about the requests. They’re the humble beginnings of adulthood, the odds and ends most college freshmen pick up on a run to Target or Walmart with their family before kissing mom goodbye and moving into the dorm.

The wesbite's sleek but playful profile pages are peppered with personal information—ViQuan’s favorite food is mac and cheese (he doesn’t specify box or homemade)—and updates like who bought what item, almost always followed by a thank you, or other response from the youth.

In Facebook the vital stats you get are recent photographs, friends, and maybe work history. In the Camellia Network, profiles tout hopes and dreams. The top of every profile reads like a Madlib that makes your heart twist.

True to their Millennial age group, most of the youths issue prolific quantities of terse dispatches. It adds up to up to an authentic post-modern biography with which donors can relate. Ashlyn revealed she’d really like to be a singer, not just a Kindergarten teacher. A steady stream of support and connection ensued, each update public, and revealing a little more about the young woman for whom the community is buying towels and flatware.

“We want to manufacture the support network that a lot of people take for granted… when they leave home at 18,” said Keigwin.

Comments range from logistical interactions sorting out why a transaction didn’t go through for a new laptop, to zealous digital embraces: “Julian, I am honored to be able to be the family you don't have to help support you and your wife. God bless,” one donor wrote after buying the 18 year-old Christian football fan toothpaste, Kleenex, and cookie pans.

There are already bonds forming between actual people revealed in the clipped public comments as a 'thank you' for a bathmat evolves into career advice. Just like within a traditional family, that first helping hand can lead to a big leg up. More broadly, it’s refreshing to see the technology that’s taking over our lives used to improve someone else’s: a social network isn’t just connecting you with your old high school crush, it’s also letting people who couldn’t normally help out on this cause make a difference in a new way.

“Even for those people who don’t have that life experience who can do something, who can offer something, it is meaningful,” says Commissioner Brian Samuels of the federal government’s Administration on Children Youth and Families.

He says, “having access to positive human beings means you have the potential for connecting in positive relationships,” something former foster children by definition are sorely lacking. He tells GOOD that first and foremost he wants to see more constructive opportunities within the foster system to help the 400,000 kids succeed, not just after. Too often the urgent needs of extracting a child from abuse and finding a permanent home can crowd out attention to more ambitious goals like long term mental health, cultivating lasting mentor relationships, or making preparations for successful adulthood.

There has been some success through new “supportive housing” programs that bundle social services and counseling with affordable housing to help families stay together. One successful pilot program his agency is repicating is aptly called Keeping Families Together. The Department of Health and Human Services, ACYF's parent agency, is exploring a similar plan for after foster care.

No one solution will end the cycle of neglect or one sector of society. The Camellia Network is tiny compared to the need, but it's also the low bar for the general public to make a difference, and a visible one. The network is growing: in the one month since launch it has expanded from serving 50 or so young adults, to over 80, each one vetted by local agencies confirming they truly are former foster kids in need. About 750 people have joined the social network as potential donors, collectively giving $16,000 in the first three weeks of operations.

Keigwin doesn't pretend her group or her plan will have the resources for all 30,000 kids to be on site anytime soon. “These youth have been let down time and time again, so we are building the community slowly. When we see enough community and financial support we will expand,” she says.

Being a foster parent is a high bar to help. Like many new media moves to ameliorate social ills, this one let’s people who could never join a cause participate purposefully from the fringes and ease their way in. In this case, the network format also invites in companies.

Puma is sending birthday gifts. Sesame Street is offering internships in their NY office. One former foster child has donated a scholarship.

“The problem isn’t a lack of resources for these people," says Keigwin. "It’s that there’s never been an easy way to get involved.”

You can join the Camellia Network here.

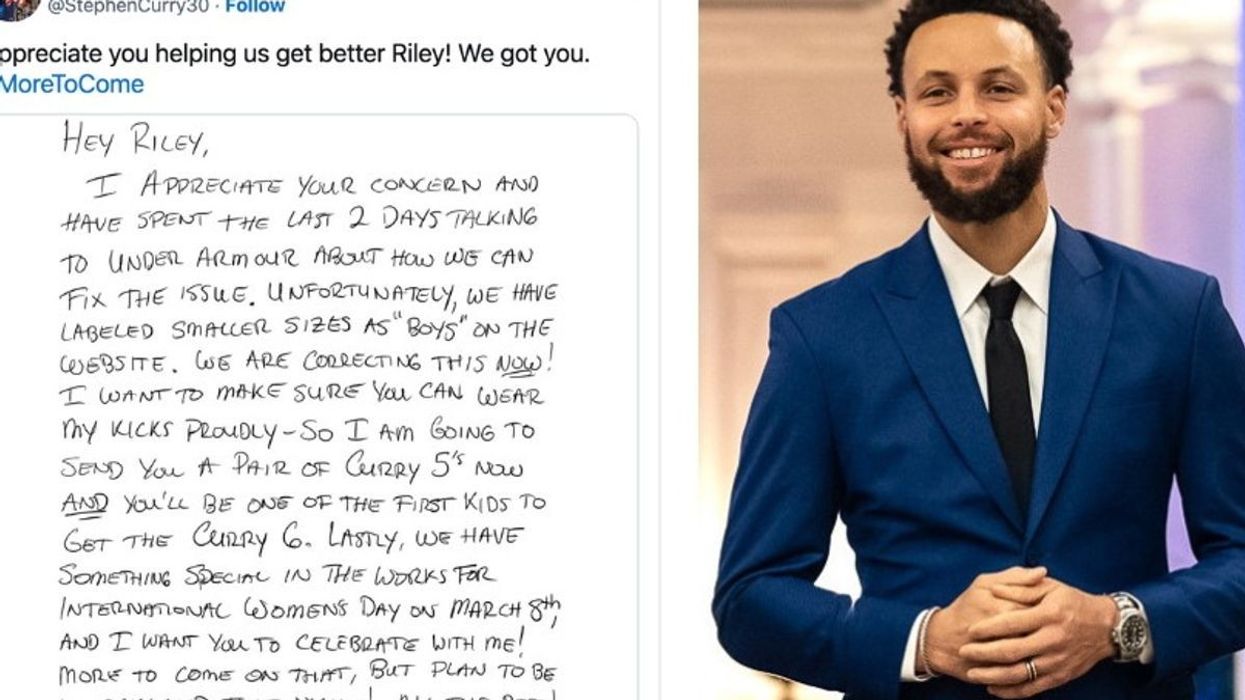

Image: Camellia Network co-founders with two youth members, via the Camellia Network Facebook page.