American documentary filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer has spent more than a decade of his career attempting to lift the veil of forgetfulness hanging over one of the postwar era’s worst mass murders—the killing of as many as 1 million Indonesians in 1965 and 1966 by military and right-wing forces, ostensibly reacting to a failed Communist coup.

It’s not as if the massacres were ignored at the time; they were widely reported, including extensive photographic coverage in Life and other international magazines. A successful film with the failed coup as its backdrop—The Year of Living Dangerously—helped make Mel Gibson an international star in 1982.

Gradually, however, the memory of these killings faded outside Indonesia, where families were forced to mourn their dead in silence by decade after decade of authoritarian repression. The United Sates, which regards Jakarta as an important economic partner and ally in the struggle against Islamic extremism, was just as happy to see the silence deepen, since it was widely suspected at the time that American intelligence agencies colluded in the anti-Communist violence.

Oppenheimer, 41, has now produced two critically acclaimed films that attempt to expose these atrocities amid strong resistance from Jakarta and silence from Washington. His first film on the murders, The Act of Killing, garnered an Academy Award nomination. So, too, has Oppenheimer’s latest installment, The Look of Silence, which follows one man’s attempt to identify and confront his brother’s killers. Since it premiered last year at the 71st Venice International Film Festival, The Look of Silence has received worldwide attention, recently receiving the prestigious Peace Film Prize at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival.

“Indonesians have courageously used the films to prompt and energize their movement against impunity,” Oppenheimer tells GOOD. And with The Look of Silence nominated for an Academy Award, “the number of people seeking out the film has suddenly skyrocketed. It takes the discussion to a whole new level.”

Oppenheimer is making the most of his awards-season megaphone. He’s now attempting to step up the pressure on Congress and the Obama administration to formally acknowledge whether U.S. intelligence agencies played a role in the mass killings by providing Indonesian authorities with lists of suspected Communists and other leftists marked for elimination.

Joined by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, this week Oppenheimer will screen The Look of Silence for a Washington, D.C., audience whose invitees include members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and their House counterparts, officials from the Department of State, and members of the White House National Security Council staff. The screening will be followed by a question-and-answer session with Oppenheimer and Adi Rukun, the documentary’s protagonist.

Oppenheimer has also packed his D.C. schedule with private meetings with government officials, hoping to rally support for New Mexico Senator Tom Udall’s resolution condemning the mass killings in Indonesia and calling for the State Department to declassify documents relating to American involvement in the crackdown that precipitated them. Release of those documents, activists say, would not only provide a measure of accountability for Washington’s actions, but also push forward efforts to lift restrictions on free expression in contemporary Indonesia.

Despite the positive reaction around the world to both his documentaries, Oppenheimer knows he is facing an uphill battle in getting the United States to admit its role, not only because of the implications raised by possible American involvement in the slaughter, but also because the current Jakarta regime, though authoritarian, is an important U.S. ally.

“Although there is now pressure emerging from the Senate for the U.S. to acknowledge its role, that’s different than the executive branch actually doing it,” says Oppenheimer.

In his role as president, Barack Obama, whose mother moved out of Indonesia with her two children during the period following the mass killings, faces a difficult diplomatic dilemma.

“The United States isn’t just insisting that Indonesia is an economic partner, but it’s a key counterweight, strategically, to the growing influence of China,” Oppenheimer says. “There are all sorts of strategic and commercial reasons why the U.S. doesn’t want to strain relations.”

“Our argument to Washington is there is no reason to strain relations,” he adds. “The U.S. and Indonesia together committed this crime. All that’s required of the United States is the moral courage to say, ‘Hey, we did this.’ Indonesia, as the result of The Act of Killing, acknowledged that this was a crime against humanity and there needs to be truth, justice and reconciliation.’’

This week, the filmmakers will launch two online actions, one aimed at Indonesian president Joko Widodo, whose regime continues to limit free expression concerning the massacres, and the other pointed at U.S. senators. The lawmakers will be urged to support Udall’s Resolution 273.

“It is unacceptable that after 50 years, the families of possibly as many as 1 million victims from the Indonesian massacres of 1965-66 have not be able to seek justice or accountability,” says Amnesty International USA’s Asia director, T. Kumar. “Indeed, they have not even been allowed to have a public discussion on what took place. As long as the wall of silence remains, the culture of impunity will continue and will negatively impact the country.”

Oppenheimer’s documentaries have restored factuality to the vague memories of massacre that have lingered in Indonesia for the past half-century. The killings began after a failed 1965 Communist coup that was so badly organized and ill supported it collapsed almost immediately and involved barely a dozen fatalities. The country’s military, and death squads organized by major landowners, used the unsuccessful putsch as an excuse to begin an extermination campaign targeting alleged Communists, leftists, and union members across the archipelago. Eventually, Christians and ethnic Chinese also were targeted; somewhere between 500,000 and 1 million people were killed—often hacked to death—with another 1 million imprisoned.

Because he spent a part of his primary school years living in Indonesia, and because he has given special attention to U.S. relations with the Muslim world, Obama is thought by many knowledgeable activists to have a special interest in the issues raised by the two films. Oppenheimer says Obama’s sister, Maya Soetoro-Ng, who was born in Indonesia in 1970, was given a copy of The Look of Silence. “I have a hunch that Obama may have seen the film,” Oppenheimer says.

While both films were initially banned in Indonesia, they’ve been in wide theatrical release for the past year. On December 10, International Human Rights Day, the filmmakers made The Look of Silence available on YouTube and as a free download for all Indonesians. Both of the documentaries have been viewed thousands of times in Indonesia, sparking a national conversation as Jakarta struggles with grafting old-school repression onto the digital age.

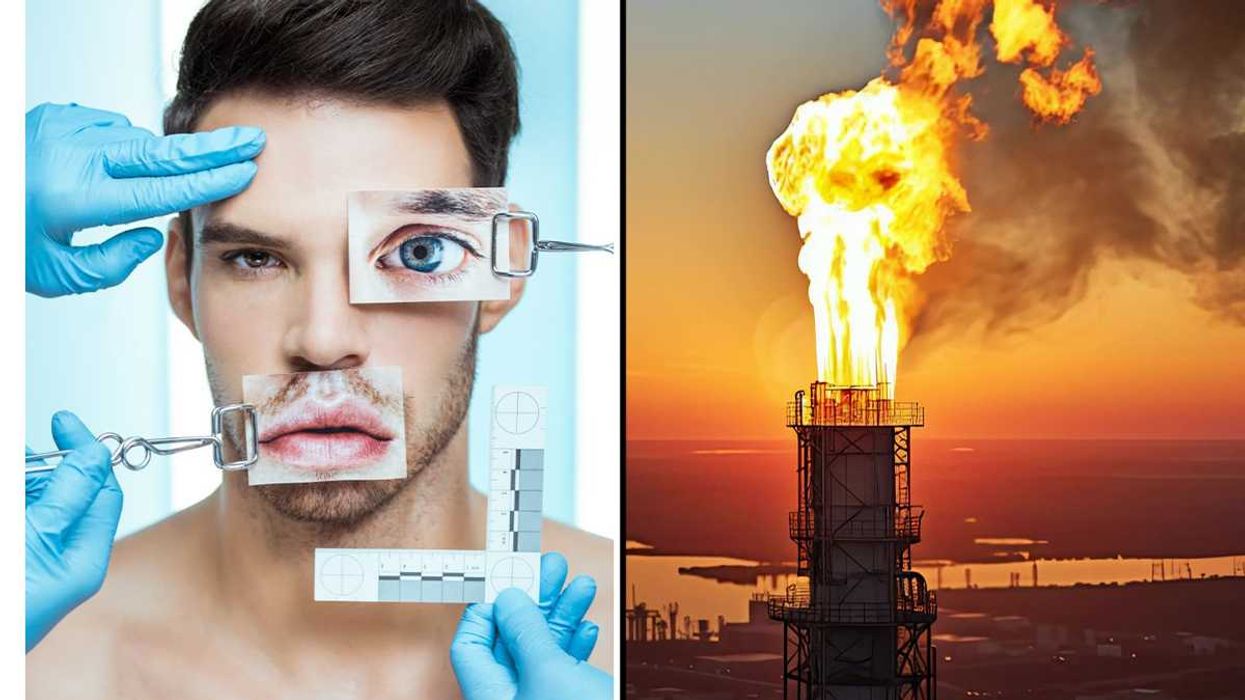

Many of those involved with the film’s social action campaign believe that their efforts may give a boost to Indonesians’ civil liberties, allowing them to begin prying open the nexus of military, socially conservative, and oligarchic connections that comprise Jakarta’s version of the invisible “deep state.” That, in turn, might even create the transparency required to begin addressing one of the world’s most troubling current environmental problems: the illegal burning of Indonesia’s native hardwood forests to make way for palm oil plantations—a matter that scientists say has pushed the world into the danger zone on global warming.

“In a sense the genocide was a strategy to traumatize the public so they would be too afraid to stand up to this kind of plunder,” says Oppenheimer, who has been banned by the Indonesian government from entering the country. “Although my films are about an issue that may seem far away and long ago, our survival may just depend on the movement against impunity that the two films are inspiring.”

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.