Gregory Jones, his head shrouded in a thick black hoodie, doesn't look up as he trudges past a tidy row of condominiums that stands on the site of his boyhood home. All week, violent winds have whipped cold rain around Chicago, but his oversized leather jacket, which hangs almost to his knees, manages to keep him dry. He shuffles along the pavement, past a brand-new police station, and across Division Street, to a section of the Cabrini-Green housing projects known as the Whites-"Whites" because the eight buildings once gleamed, a symbol of a city's problems solved. Now, the three remaining towers have turned ashen. From the burned-out windows, the last remaining residents of Cabrini can glimpse both the past and the future: empty parking lots on one side; snaking rows of identical town houses on the other.Growing up, this is where Gregory, now 22, spent his weekends. He was an only child, a neighborhood rarity, but had plenty of friends and cousins to play with in the Whites. It was home to his great-grandmother, his maternal and paternal grandmothers, his friends, and all the girls with whom he liked to flirt. It was also where he played baseball-not the most popular sport at Cabrini-Green, but one that suited an athletically gifted kid who didn't want to be another point guard. It gave him something to do other than hang out with older guys, who were invariably getting into trouble. "It was heaven," he says.It was here, crossing these same streets 17 years ago, that Gregory fled from gang gunfire with his father and mother. He remembers the bullets striking at their feet, slashing the pavement. "My mother tripped when she was running across the street," he says. "I thought she'd been hit, and I was screaming and screaming...I mean, if it happened now, it wouldn't really be anything, but I was 5."Gregory's childhood ended the day before his 10th birthday, when his family was evicted from their apartment, his mother in the grips of a crack addiction. Two years later, his good friend, known as "Girl X" in the papers, was raped, beaten, and poisoned in a Cabrini-Green stairwell. Though eclipsed by the JonBenet Ramsey murder in Colorado, the 1997 incident made national headlines, bringing even more attention to the blighted project, which, after years of neglect by the local housing authority, was desperate for an answer to its problems.You hear it all over the city, from anyone you care to ask: Mayor Richard M. Daley has a vision for downtown Chicago, and through sheer force of will, he is making it come to pass. On his watch (if he has his way) Chicago will blossom from a workingman's town, where the streets are deserted before happy hour ends, to a cosmopolitan destination on a par with New York. To do this, the city will bid to host the 2016 Olympics; it will "solve" its crime and gang problems; it will even reinvent public housing as we know it. And to do that, Chicago will have to tear down the worst of it.Cabrini-Green is Chicago's best-known housing project, and was the first to see the wrecking ball. At its height, Cabrini was home to 15,000 residents spread over 15 red-brick high-rises (the "Reds"), eight 16-story towers (the "Whites"), and a patch of street-level row houses. The row houses, built in 1942, were originally home to Italian immigrants; 15 years later, the high-rises began to go up to accommodate the growing number of Southern blacks moving to Chicago. Before long, Cabrini-Green became a segregated black ghetto with a reputation for crime, poverty, and urban decay.By 2000, the Chicago Housing Authority was entrusted with a $1.4 billion budget to overhaul its public housing, with much of the initial funding coming from the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Finally, after decades of neglect and agency corruption, the CHA-which had been taken over for a time by HUD-would begin dismantling its public housing system in a strategy called the Plan for Transformation or, more simply, the Plan.The Plan was originally scheduled for completion next year, but the deadline has been extended to 2015, due in part to tenant litigation and the drying up of federal funds. When it's done, 25,000 public-housing units will have been razed or rehabilitated across the city. The impact of the Plan on the city's landscape is already unmistakable. Cabrini-Green, once a massive cluster of high-rises and row houses just a 10-minute walk from the elegant stores of Michigan Avenue, is mostly gone. A handful of buildings remain, surrounded on all sides by new condominiums and booming retail stores. Twenty percent of these condos have been set aside as affordable housing; a third will be public housing. The rest are selling for up to $850,000 a piece. Since the Plan launched, in 2000, more than $2 billion in residential property has been sold within two blocks of Cabrini.Residents who have moved into the mixed-income developments seem to love it. Jeremy Smith, an upbeat, alert 25-year-old who lives with his mother, talks about an improved quality of life, even though he sometimes gets the cold shoulder from their neighbors. But Jeremy appears to be an exception. Recent research shows that two-thirds of the Housing Authority tenants who apply for mixed-income units are finding their applications denied, for a growing number of reasons (poor credit, a history of late rent payment, family members with criminal records). When the Plan came to Cabrini, all lease-abiding residents were given a legal "right to return" to a new apartment on-site, but those who didn't want to wait years for a new home, or who feared they wouldn't qualify, could take a rent subsidy voucher, called a Section 8, and live elsewhere. More than 80 percent of the tenants who opted for this voucher have moved to areas of Chicago more segregated, isolated, and poor than Cabrini had been.Despite its flaws, the Plan has enormous support, and not only in Chicago. "We are pointing the way to the future for the rest of the country," says the Housing Authority's Bryan Zises. And, indeed, the rest of the country is paying attention: Miami announced recently that it will pursue a similar strategy, joining other American cities already following Chicago's lead. What this will mean for the country's urban poor is not yet known-whether plans like this will deliver their promise of safe, improved shelter, or merely serve as city-sponsored gentrification schemes, reducing the amount of safe housing available to the country's neediest people. Public-housing advocates express concern about the implementation of such a national-scale strategy before the real human costs can be measured."Like all large plans, this one has winners and losers," says Lawrence Vale, a public-housing expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "The Plan works best for those people who are already well equipped for self-transformation, because they have job skills, good health, and more extensive social networks, so that they are more likely to benefit from alternative housing opportunities. For others, exiting public housing may simply replace one inadequate living situation with another." As Vale suggests, Chicago's Plan is working to create two classes of the extremely poor. On one side are people like Jeremy, who've inched higher, toward better living conditions. On the other are people like Gregory.

|

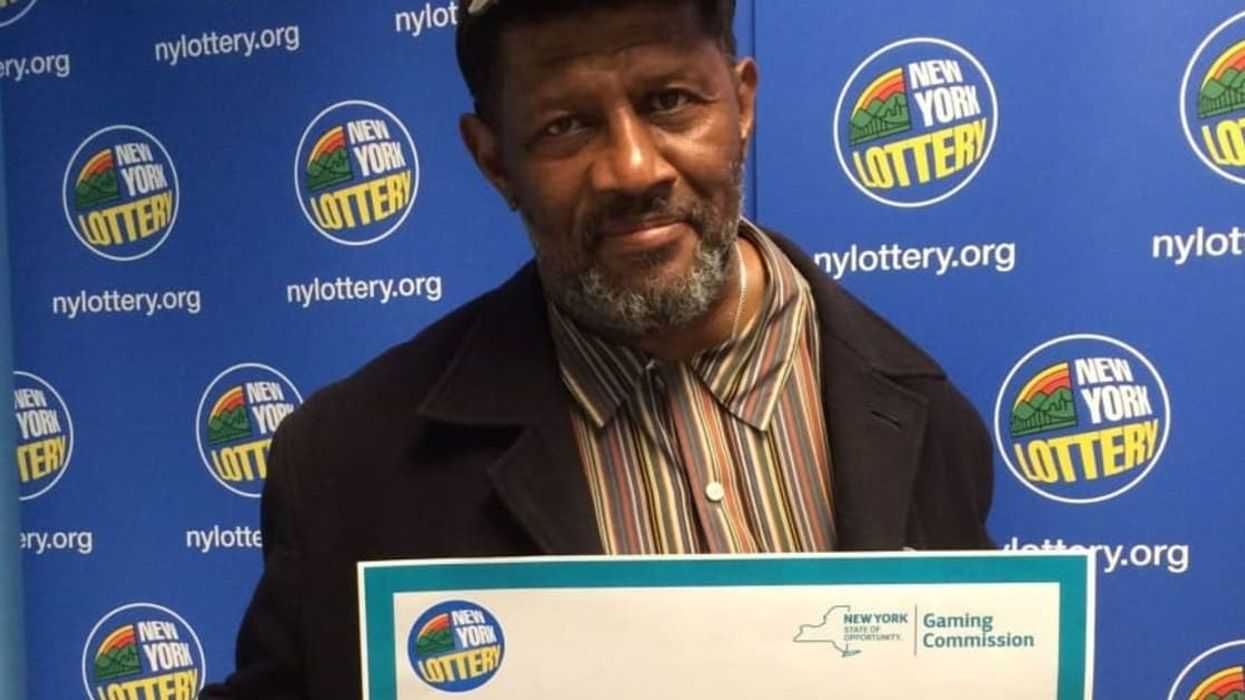

| Gregory Jones stands at 1230 North Larrabee, one of Cabrini-Green's last towers. |

| Quote: |

| The problem we have as a nation is that policymakers and city officials tend to be better at mixing out the poor than mixing them in. |

|

| A mixed-income development on West Division Street overlooks Seward Park. |

|

| Jeremy Smith stands before a mural on North Clybourn Avenue at Cabrini-Green. |

| Quote: |

| There used to be these community stores where you could go in and get what you need, priced to people like my family. But now it's these furniture stores that are real exquisite. |

| Quote: |

| There are also thousands among Chicago's urban poor just like Gregory, who have not seen transformation as much as elimination. In a sense, they've been wiped off the map entirely. |

|

| Only a few of the buildings at Cabrini-Green are still standing. |

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.