We’re a quarter through 2019 and there has already been more measles cases in the first two months of this year than in all of 2017. A major reason for this is the growing number of unvaccinated children in the U.S.

Ninety-two percent of U.S. children have received the MMR vaccine, while that number seems high, the number of children under two who haven’t received any vaccinations has quadrupled in the last 17 years.

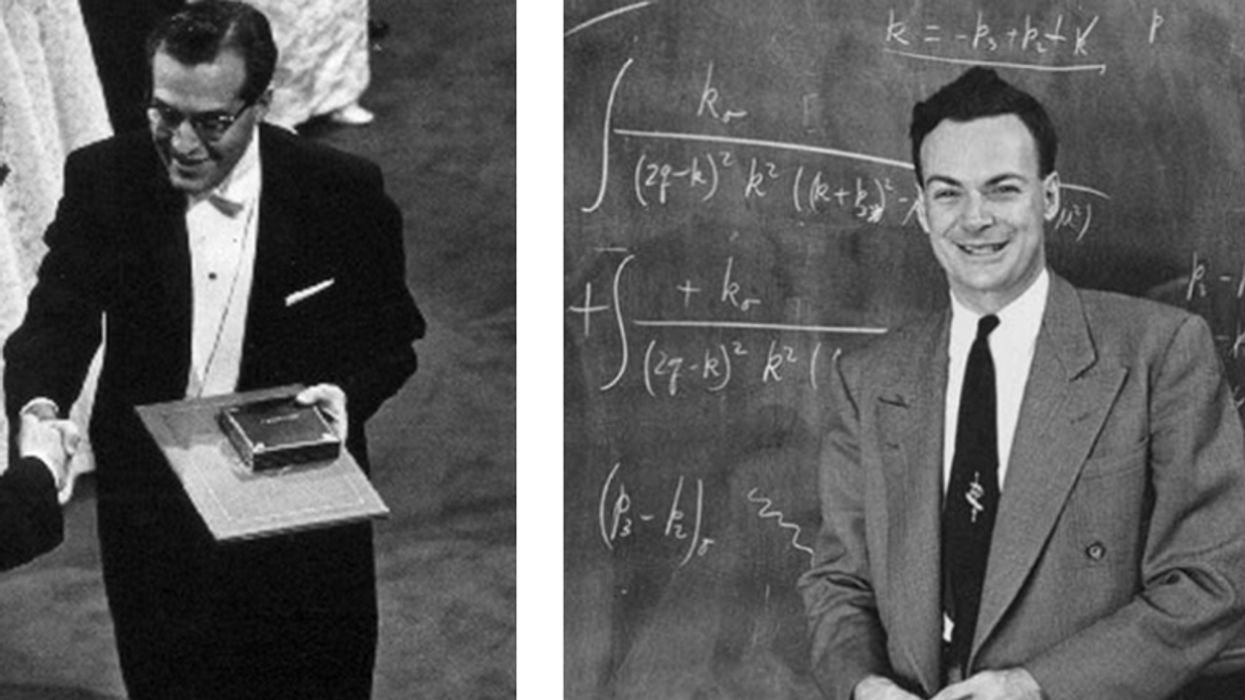

The rise of the anti-vaxxer movement is a major reason for the increase in measles and unvaccinated children. In 1998, a study by Andrew Wakefield that linked vaccines to autism published in the medical journal The Lancet, kicked off the modern anti-vaccine movement.

The study was later debunked and Wakefield lost his medical license.

Since Wakefield’s fraudulent study was released, there have been over 140 peer-reviewed articles, published in relatively high impact factor or specialized journals that document the lack of a correlation between autism and vaccines.

Now, a new study involving over 650,000 children, has also concluded that the MMR vaccine doesn’t cause autism.

Researchers used a population registry of children in Denmark between 1999 and 2010 to see if the MMR vaccine increased the risk of autism. Ninety-five percent of the 657,461 children were given the MMR vaccine and and 6,517 were diagnosed with autism.

According to the study published in in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine, the MMR vaccine didn’t increase the risk of autism in children not considered at risk for the disorder or trigger its onset in those considered at risk.

Unfortunately, the new study may not change many minds in the anti-vaxxer community. In 2005 and 2006, researchers at The University of Michigan found that that when people are confronted with facts that disprove their closely-held beliefs, they often become more strongly set in their beliefs.

Otis knew before they did.

Otis knew before they did.