If you could be one age for the rest of your life, what would it be?

Would you choose to be nine years old, spending your days playing with friends and practicing your times tables?

Or would you choose your early 20s, when time feels endless and the world is your oyster with friends, travel, pubs and clubs?

Western culture idealizes youth, so it may come as a surprise to learn that in a recent poll asking this question, the most popular answer wasn't 9 or 23, but 36.

Yet as a developmental psychologist, I thought that response made a lot of sense.

For the last four years, I've been studying people's experiences in their 30s and early 40s, and my research has led me to believe that this stage of life, while full of challenges, is much more rewarding than most might think.

The career and care crunch

When I was a researcher in my late 30s, I realized that no one was doing research on people in their 30s and early 40s, which puzzled me. So much often happens during this time: Buying homes, getting married or getting divorced; building careers, changing careers, having children or choosing not to have children.

To study something, it helps to name it. So my colleagues and I named the period from ages 30 to 45 "established adulthood" and then set out to try to understand it better. While we are still collecting data, we have interviewed over 100 people in this age cohort and collected survey data from more than 600 additional people.

We went into this large-scale project expecting to find that established adults were happy but struggling. We thought there would be rewards during this period of life, perhaps being settled in career, family, and friendships, or peaking physically and cognitively, but also some significant challenges.

The main challenge we anticipated was what we called "the career and care crunch."

This refers to the collision of workplace demands and the demands of caring for others that occurs in one's 30s and early 40s. Trying to climb a ladder in one's chosen career while also being increasingly expected to care for kids, tend to the needs of partners and perhaps care for aging parents.

Yet when we started to look at our data, what we found surprised us.

Yes, people were feeling overwhelmed and talked about having too much to do in too little time. But they also talked about feeling profoundly satisfied. All of these things that were bringing them stress were also bringing them joy.

For example, Yuying, 44, said, "Even though there are complicated points of this time period, I feel very solidly happy in this space right now." Nina, 39, simply described herself as being "wildly happy." (The names used in this piece are pseudonyms, as required by research protocol.)

When we took an even closer look at our data, it started to become clear why people might wish to remain age 36 over any other age. People talked about being in the prime of their lives and feeling at their peak. After years of working to develop careers and relationships, people reported feeling as though they had finally arrived.

Mark, 36, shared that, at least for him, "things feel more in place." "I've put together a machine that's finally got all the parts it needs," he said.

A sigh of relief after the tumultuous 20s

As well as feeling as though they had accumulated the careers, relationships and general life skills they had been working toward since their 20s, people also said they had greater self-confidence and understood themselves better.

Jodie, 36, appreciated the wisdom she had gained as she reflected on life beyond her 20s:

"Now you've got a solid decade of life experience. And what you discover about yourself in your 20s isn't necessarily that what you wanted was wrong. It's just you have the opportunity to figure out what you don't want and what's not going to work for you. So you go into your 30s, and you don't waste a bunch of time going on half dozen dates with somebody that's probably not really going to work out, because you've dated before and you have that confidence and that self-assuredness to be like, 'Hey, thanks but no thanks.' Your friend circle becomes a lot closer because you weed out the people that you just don't need in your life that bring drama.

Most established adults we interviewed seemed to recognize that they were happier in their 30s than they were in their 20s, and this impacted how they thought about some of the signs of physical aging that they were starting to encounter. For example, Lisa, 37, said, "If I could go back physically but I had to also go back emotionally and mentally no way. I would take flabby skin lines every day."

Not ideal for everyone

Our research should be viewed with some caveats.

The interviews were primarily conducted with middle-class North Americans, and many of the participants were white. For those who are working class, or for those who have had to deal with decades of systemic racism, established adulthood may not be so rosy.

It is also worth noting that the career and care crunch has been exacerbated, especially for women, by the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, the pandemic may be leading to a decrease in life satisfaction, especially for established adults who are parents trying to navigate full-time careers and full-time child care.

[You're smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation's authors and editors.You can get our highlights each weekend.]

At the same time, that people think of their 30s and not their 20s or their teens as the sweet spot in their lives to which they'd like to return suggests that this is a period of life that we should pay more attention to.

And this is slowly happening. Along with my own work is an excellent book recently written by Kayleen Shaefer, "But You're Still So Young," that explores people navigating their 30s. In her book she tells stories of changing career paths, navigating relationships and dealing with fertility.

My colleagues and I hope that our work and Shaefer's book are just the beginning. A better understanding of the challenges and rewards of established adulthood will give society more tools to support people during that period, ensuring that this golden age provides not only memories that we will fondly look back upon but also a solid foundation for the rest of our lives.

Clare Mehta is an Associate Professor of Psychology, Emmanuel College. This article originally appeared on The Conversation. You can read it here.

This article originally appeared on 04.27.21.

More on Good.is

The Happy Post Project: Spreading Cheer Via Post-It Note - GOOD

Science just confirmed it being materialistic makes us less happy ...

Pexels | Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

Pexels | Photo by Andrea Piacquadio

An Atlantic grey seal looking at the camera underwater. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Mark Chivers)

An Atlantic grey seal looking at the camera underwater. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Mark Chivers) A grey seal swims up to a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Huw Thomas)

A grey seal swims up to a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Huw Thomas) A Grey seal nibbles at the hood of a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bernard Radvaner)

A Grey seal nibbles at the hood of a scuba diver. (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bernard Radvaner)

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen co-host the HFC Austin Brain Health Dinner on September 30, 2023, in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Rick Kern/Getty Images for Hilarity for Charity)

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen co-host the HFC Austin Brain Health Dinner on September 30, 2023, in Austin, Texas. (Photo by Rick Kern/Getty Images for Hilarity for Charity) Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards on March 12, 2023 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images )

Image Source: Seth Rogen and Lauren Miller Rogen attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards on March 12, 2023 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Arturo Holmes/Getty Images ) Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |

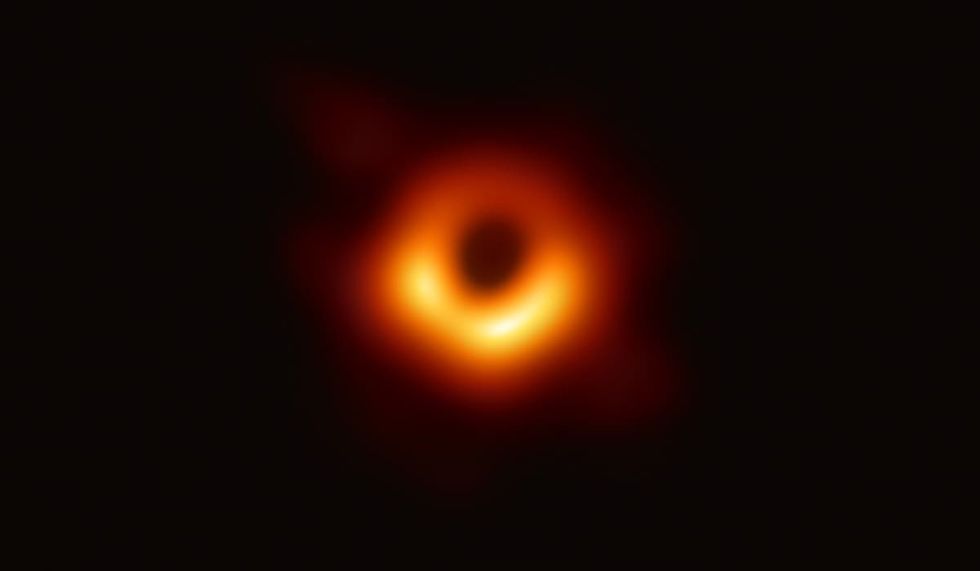

Image Source: In this handout photo provided by the National Science Foundation, the Event Horizon Telescope captures a black hole at the center of galaxy M87 in an image released on April 10, 2019. (National Science Foundation via Getty Images)

Image Source: In this handout photo provided by the National Science Foundation, the Event Horizon Telescope captures a black hole at the center of galaxy M87 in an image released on April 10, 2019. (National Science Foundation via Getty Images)

Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich

Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Image Source: Destroyed vehicles lie near the rubble after the earthquake and tsunami devastated the area on March 16, 2011, in Minamisanriku, Japan. The 9.0 magnitude strong earthquake struck offshore on March 11 at 2:46 pm local time, triggering a tsunami wave of up to ten meters which engulfed large parts of north-eastern Japan. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images)

Image Source: Destroyed vehicles lie near the rubble after the earthquake and tsunami devastated the area on March 16, 2011, in Minamisanriku, Japan. The 9.0 magnitude strong earthquake struck offshore on March 11 at 2:46 pm local time, triggering a tsunami wave of up to ten meters which engulfed large parts of north-eastern Japan. (Photo by Chris McGrath/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay Representative Image Source: Pexels | Stuart Pritchards

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Stuart Pritchards

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the 2009 American Music Awards at Nokia Theatre L.A. Live on November 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage)

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the 2009 American Music Awards at Nokia Theatre L.A. Live on November 22, 2009 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage) Image Source: Keith Urban and Nicole Kidman attend The 2024 Met Gala on May 06, 2024 in New York City. (Photo by John Shearer/WireImage)

Image Source: Keith Urban and Nicole Kidman attend The 2024 Met Gala on May 06, 2024 in New York City. (Photo by John Shearer/WireImage) Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the Oscars on February 24, 2013 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Jeff Vespa/WireImage)

Image Source: Musician Keith Urban and actress Nicole Kidman arrive at the Oscars on February 24, 2013 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Jeff Vespa/WireImage)

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu

Representative Image Source: Pexels | August de Richelieu Representative Image Source: Pexels | Djordje Vezilic

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Djordje Vezilic Representative Image Source: Pexels | Fauxels

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Fauxels