Last fall, the Central California Women’s Facility, one of the largest female prisons in California, the U.S., and the world with over 2,000 residents, began its own newspaper, The Paper Trail. Written and edited by people incarcerated within its walls, which includes women, nonbinary, and transgender individuals, The Paper Trail offers commentary, features, and interviews, like stories about what it’s like to go through menopause in prison, a prison Pride Walk, and descriptions of their in-house program discussing prison life with at-risk youth.

Among the paper’s missions, as they write on Instagram, are to “showcase and represent the people who live and work at CCWF,” “to motivate, inspire, encourage change, provide hope and share our lived experience,” and “to highlight changes within these walls, bring awareness to the wider world about what happens here, our accomplishments and our struggles.” Hoping to “represent all communities, cultures and subcultures within the institution. We want to show that CCWF residents care about giving back to society and utilize restorative justice principles to do so,” they continue.

The Paper Trail has a print run of 35,000 copies and reaches some 850,000 viewers with its print and online presences combined. Its audiences, as the editors shared with Fresno’s KVPR radio, include “the inside population, our outside community members…and the staff,” the latter of which includes people who support the paper’s existence. Recently, with a donation from rehabilitative education organization Edovo, incarcerated individuals will be able to read the paper “on tablets in 1,100+ prison and jails across the U.S., reaching over 900,000 incarcerated individuals nationwide,” where before it would have only been available to them in print.

While, ultimately, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has to approve everything that gets written–meaning that publishing investigations into the prison system will be extremely difficult, LAistshares–the newspaper’s journalists are optimistic about the paper’s possibilities for the future.

Editor Amber Bray sees working on the paper as a way to advocate for the population, she told KVPR, and Managing Editor Kanoa Harris-Pendang sees it as empowering. Residents like Nora Igova, The Paper Trail’s Art and Layout Designer, also hopes the paper will help enlighten outside residents about the lives of the facility’s incarcerated individuals. “There is still an instilled fear in the outside community around prisons. We want people to not be afraid to believe in transformation and rehabilitation, and to see us as potential neighbors,” she told newspaper the Daily Yonder, as reported by the Pulitzer Center.

The Paper Trail was started with the help of The Pollen Initiative, a nonprofit organization “dedicated to cultivating media centers inside prisons across the country” and “equipping and empowering system-impacted individuals to be community journalists and the prism into their own narratives.” Executive Director Jesse Vasquez and Editorial Director Kate McQueen work with incarcerated individuals like those at CCWF to develop "journalistic tools and platforms to tell their stories, build professional skills, and highlight the real impact of public policy on their lives and communities."

According to the academic archive JSTOR, which houses an American Prison Newspapers digital collection of over 18,000 items, prison newspapers in the U.S. date back to at least 1800. Since then, “over 700 prison newspapers have been published from U.S. prisons in all fifty states,” they write. Their collection is viewable online here.

“Incarcerated journalists walk a tightrope between oversight by administration–even censorship–and seeking to report accurately on their experiences inside,” they continue. “Some publications were produced with the sanction of institutional authorities; others were produced underground.” The collection has a special section dedicated to women’s newspapers, viewable here. In their pages, as in those of The Paper Trail, people share their own stories and offer a first-hand account of their lives.

There hadn’t been a newspaper at CCWF previously, and residents relied on The San Quentin News, a newspaper published at San Quentin Prison by a staff of incarcerated men, also assisted by The Pollen Initiative. Women didn’t have the same voice, and The Paper Trail hopes to change that. With a newspaper of their own, like those who wrote for the newspapers that came before them, their stories are theirs to tell.

Lonely dog waits for owner.

Lonely dog waits for owner.  Commenters were in supportImage via Reddit

Commenters were in supportImage via Reddit Commenters on Reddit.Image via Reddit

Commenters on Reddit.Image via Reddit Dogs can detect with something new is going on.Canva

Dogs can detect with something new is going on.Canva

A pair of scissors.

A pair of scissors. A can opener opening a tin can.

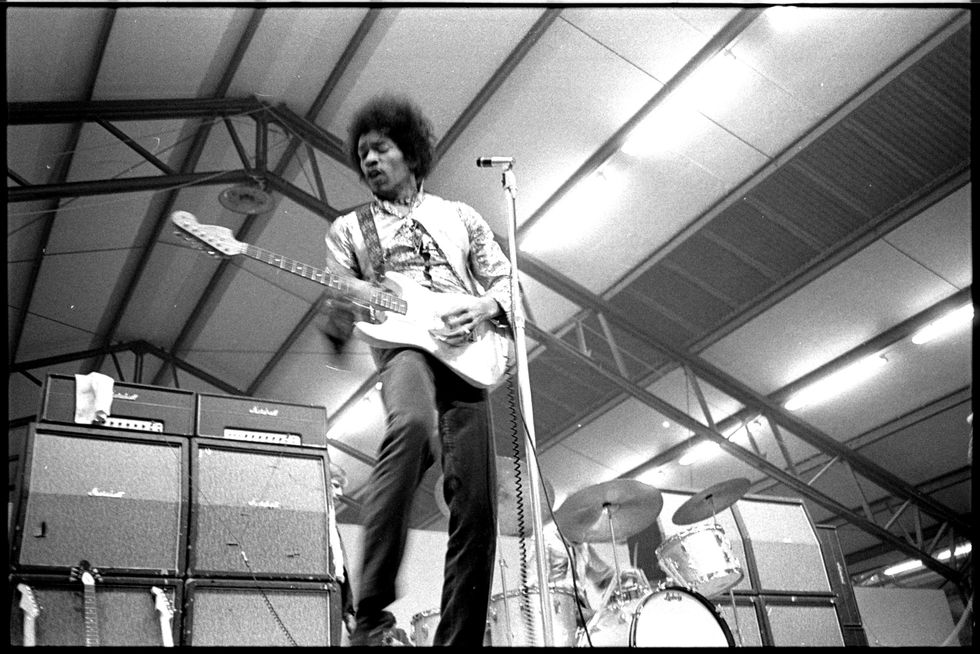

A can opener opening a tin can. Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain

Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain A man handing over $20 in cash.

A man handing over $20 in cash. A person using a power saw.

A person using a power saw.

Steve Jobs in his traditional work ensemble.

Steve Jobs in his traditional work ensemble.