There are now two COVID-19 vaccines that, at least according to preliminary reports, appear to be 94.5% and 95% effective. Both were developed in a record-breaking 11 months or so.

I am an infectious diseases specialist and professor at the University of Virginia. I care for patients with COVID-19 and am conducting the local site for a phase 3 clinical trial of Regeneron's antibody cocktail as a tool to prevent household transmission of COVID-19. I'm also conducting research on how dysregulation of the immune system during SARS-CoV-2 infection causes lung damage.

Despite the vaccines' relatively rapid development, the normal safety testing protocols are still in place.

How long does most vaccine development take?

Vaccines typically take at least a decade to develop, test and manufacture. Both the chickenpox vaccine and FluMist, which protects against several strains of the influenza virus, took 28 years to develop. It took 15 years to develop a vaccine for human papilloma virus, which can cause six kinds of cancer.

It also took 15 years to develop a vaccine for rotavirus, which commonly causes severe, watery diarrhea. It took Jonas Salk six years to develop and test the first polio vaccine, starting with the isolation of the virus.

The Pfizer-BioNTech and the Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccines, by contrast, have been developed in less than a year. That's a game-changer.

How was this vaccine developed so quickly?

The mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna are faster to develop as they do not require companies to produce protein or weakened pathogen for the vaccine.

Traditional vaccines typically use a weakened version of the pathogen or a protein piece of it, but because these are grown in eggs or cells, developing and manufacturing vaccines takes a long time.

By contrast, by using just the genetic material that makes the Spike glycoprotein – the protein on the surface of the coronavirus that is essential for infecting human cells – the design and manufacture of the vaccine is simplified.

The genetic material mRNA is easy to make in a laboratory. Manufacturing an mRNA vaccine rather than a protein vaccine can save months, if not years.

Another factor that accelerated vaccine development was the swift and efficient recruitment of patients for clinical trials.

How is safety assured when vaccine development is so fast?

Safety is the first and foremost goal for a vaccine.

In my opinion, safety is not compromised by the speed of vaccine development and emergency use authorization. The reason that vaccines may be approved so quickly is that the large clinical trials to assess vaccine efficacy and safety are happening at the same time as the large-scale manufacturing preparation, funded by the federal government's Operation Warp Speed program.

Typically, large-scale manufacturing begins only once the vaccine has been tested in clinical trials.

In the case of COVID-19, the U.S. government wanted to be ready to begin distributing the vaccine the moment the results of the phase 3 trials were known and the safety data had been analyzed.

To this end, the pharmaceutical companies launched at-risk manufacturing – which means that the manufactured vaccine doses would be thrown away if the vaccine was ineffective or unsafe – during the FDA-mandated two-month safety waiting period.

The upside is that if the vaccine is safe and effective, it can be distributed immediately, and vaccination can begin.

Are these vaccines riskier than others?

No mRNA vaccines have been approved before because it is relatively new technology.

But these mRNA vaccines appear safe and no riskier than other tried and tested ones, like the childhood measles vaccine. To date, no significant side effects have been reported in the interim phase 3 studies of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines.

Side effects that have been reported are minor things that one would expect with any vaccine, including soreness at the site of injection and transient fatigue, muscle or joint aches.

How will EUA work?

EUA stands for emergency use authorization.

Under EUA, the FDA is requiring that a COVID-19 vaccine be at least 50% effective at preventing symptomatic illness.

It is also requiring a median of two months of follow-up after completion of the vaccination for half of the vaccine recipients (for most of the vaccines this is two doses). This two-month period is to allow detection of an adverse event from the vaccine.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. You can read it here.

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Working out with friends also makes exercise more enjoyable (and feel quicker).Photo credit: Canva

Working out with friends also makes exercise more enjoyable (and feel quicker).Photo credit: Canva

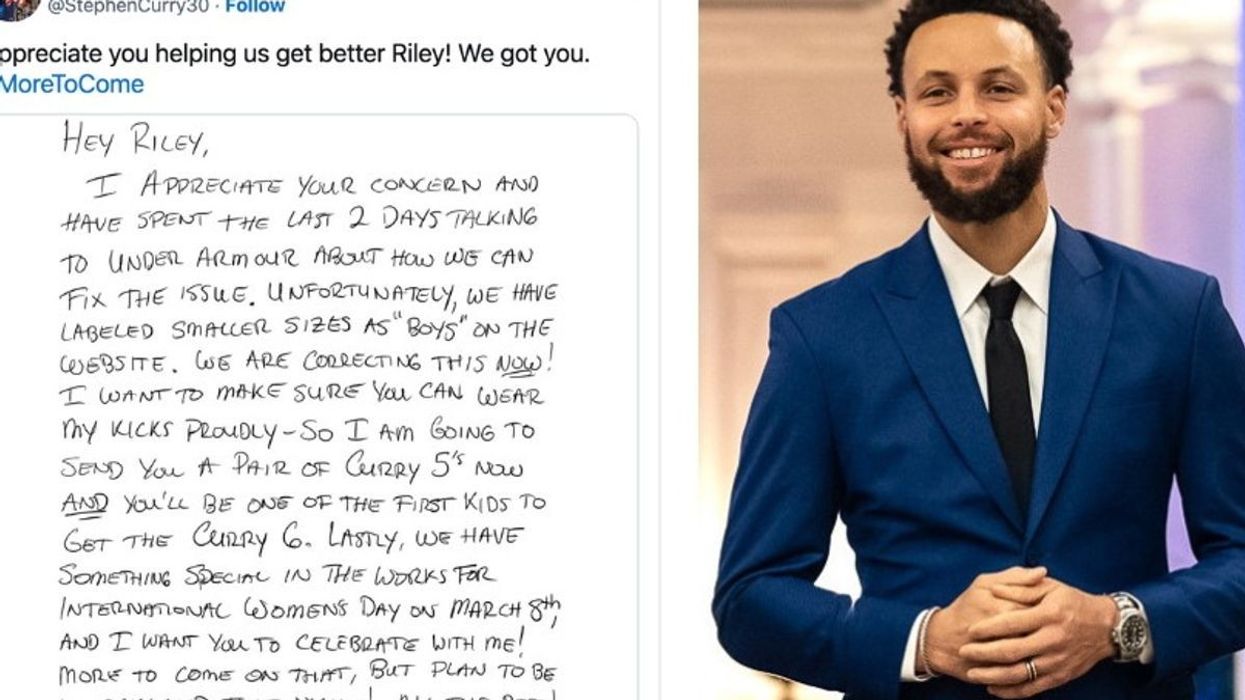

People with Imposter Syndrome can't accept their achievements.

Photo by

People with Imposter Syndrome can't accept their achievements.

Photo by  Emotion Feeling GIF by Quilt

Emotion Feeling GIF by Quilt Psychologist - Free of Charge Creative Commons Notepad 1 image

Psychologist - Free of Charge Creative Commons Notepad 1 image

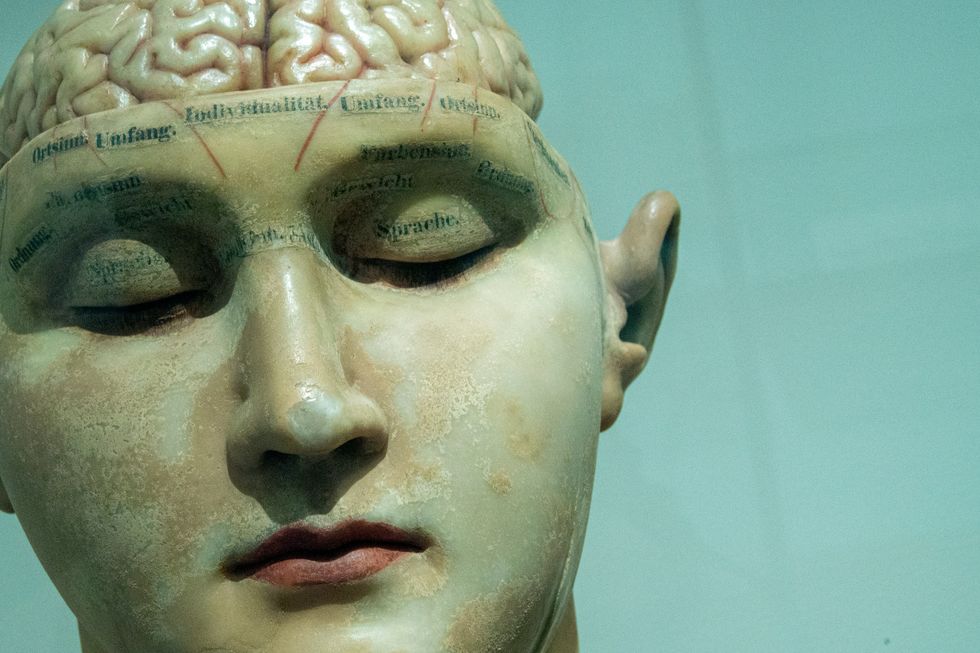

Human anatomy model.

Photo by

Human anatomy model.

Photo by

Socks warm your feet, but cool your core body temperature.Photo credit: Canva

Socks warm your feet, but cool your core body temperature.Photo credit: Canva

A new t-shirt could open up more hospital beds for patients.Photo credit: Canva

A new t-shirt could open up more hospital beds for patients.Photo credit: Canva Wearable solutions could be revolutionary.Photo credit: Canva

Wearable solutions could be revolutionary.Photo credit: Canva Many wearable tech devices could help you monitor your health.Photo credit: Canva

Many wearable tech devices could help you monitor your health.Photo credit: Canva