Inside a dimly lit hall of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, visitors can catch a glimpse of a skeleton propped up in a green cabinet. It is the place where the museum displays dinosaur bones. But this skeleton belongs to the body of Grover Krantz, an eccentric teacher and anthropologist. The strangest part of this skeleton is that there are, actually, two skeletons – one of Krantz, and the other of his beloved pet dog, an Irish wolfhound named Clyde. This was Krantz’s bizarre condition before he donated his body for scientific experiments, per Washington Post.

Grover was an outrageous man and a legend in Berkeley in the '60s, known for things like parties, wild ideas, and real smart conversations. Sometime before he passed away from pancreatic cancer, Krantz said to Smithsonian anthropologist David Hunt, "I've been a teacher all my life and I think I might as well be a teacher after I'm dead, so why don't I just give you my body."

When Hunt agreed, Krantz stated his condition, "But there's one catch: You have to keep my dogs with me." And so, apart from Clyde, the surrounding shelves hold the bones of two more wolfhounds, Icky and Yahoo. "Grover wanted to be with his dogs because he loved them," said Laurie Burgess, another Smithsonian anthropologist. After he died in 2002, there was no funeral. Instead, his body was taken to the University of Tennessee’s body farm, where scientists study human decay rates to aid in forensic investigations, per The Smithsonian.

Apart from being an oddball professor, an anthropologist, and a pet lover, Krantz was also widely known for his belief in “Sasquatch.” According to Live Science, Sasquatch, also called “Bigfoot,” is a giant, hairy, ape-like creature that some people believe roams North America. During his lifetime, Krantz was severely obsessed about finding Bigfoot and he was even certain that he would find one.

UC Berkeley Alumni Association reports an incident from the 1990s. In the lush Olympic Peninsula, Krantz was engaged in building a helicopter to find Sasquatch. He ordered the kit from some guy in the Midwest and spent several years trying to assemble it. He hoped the equipment would provide the aerial view necessary to locate a Bigfoot. Although he failed in this attempt, he was undeterred. But within him, the belief that Bigfoot exists was not to be quelled so easily.

Though he didn’t come across a Bigfoot, dead or alive, later in his research, Krantz concluded that Bigfoot was likely “Gigantopithecus,” an extinct Asian primate that existed from around nine million to one hundred thousand years ago. “It has not yet been established that the Sasquatch exists,” Krantz wrote in his book “The Scientist Looks at Sasquatch.”

However, despite his bizarre image among his colleagues, he was a brilliant scientist and made several contributions to science during his life span. He studied fossils and skeletons and made intelligent discoveries. He was the first person to explain the function of the mastoid process; plus, he proved that “Ramapithecus,” an extinct primate genus, was not ancestral to humans. He was also a pivotal contributor in the case of Kennewick Man, which involved 8,400-year-old skeletal remains found on the banks of the Columbia River in 1996. Despite his high IQ, some people thought that he was too intelligent for his own good.

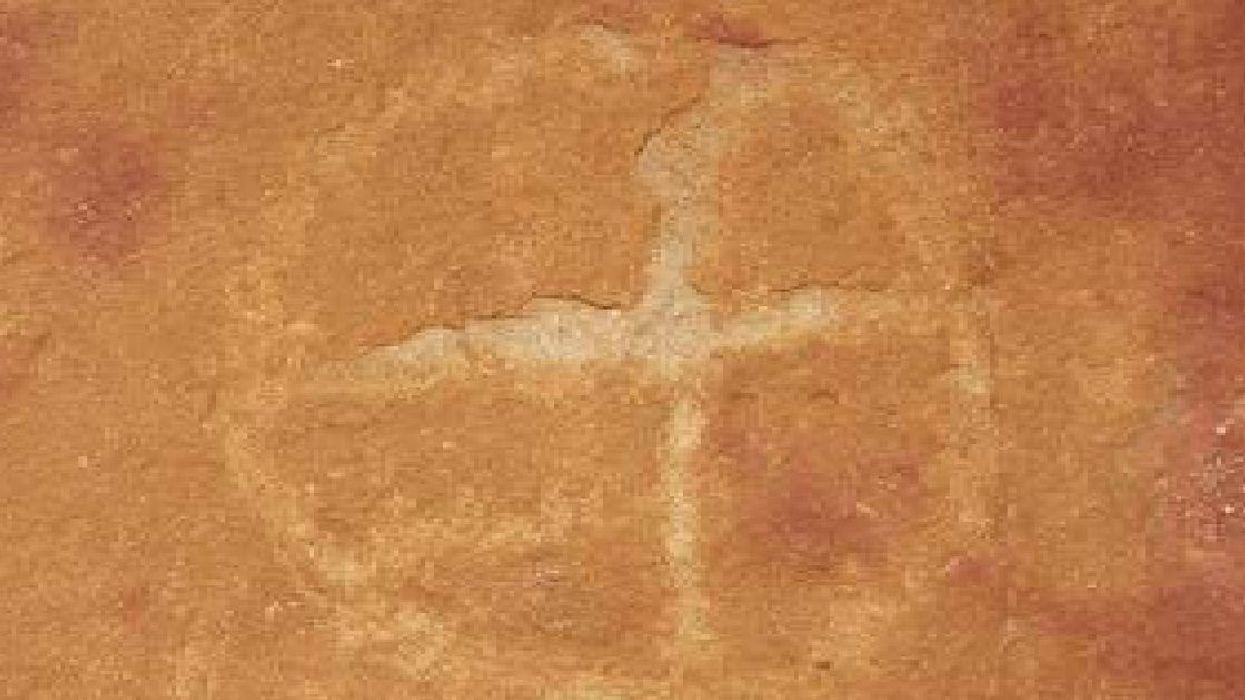

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:

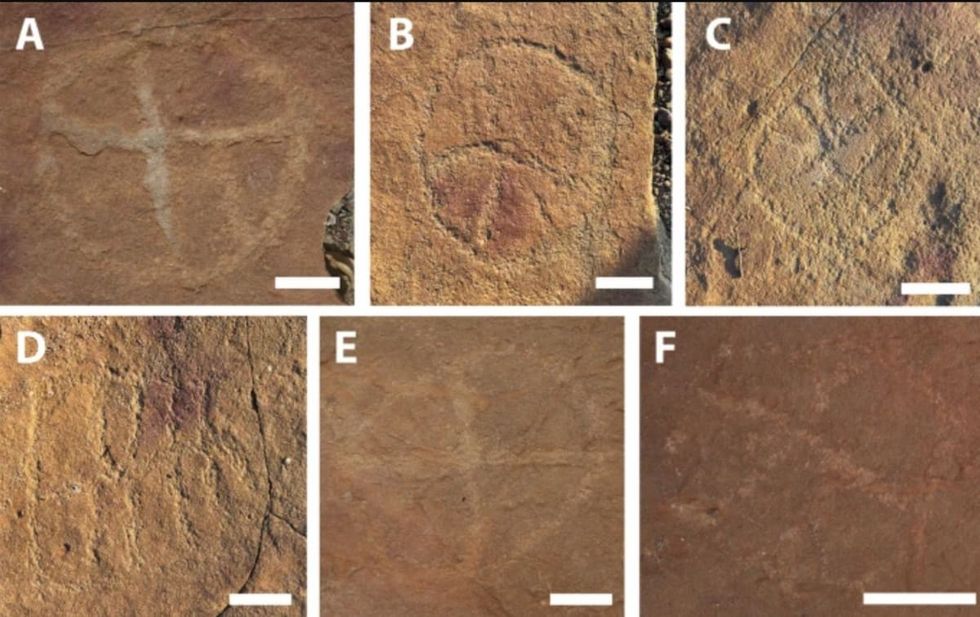

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork. Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

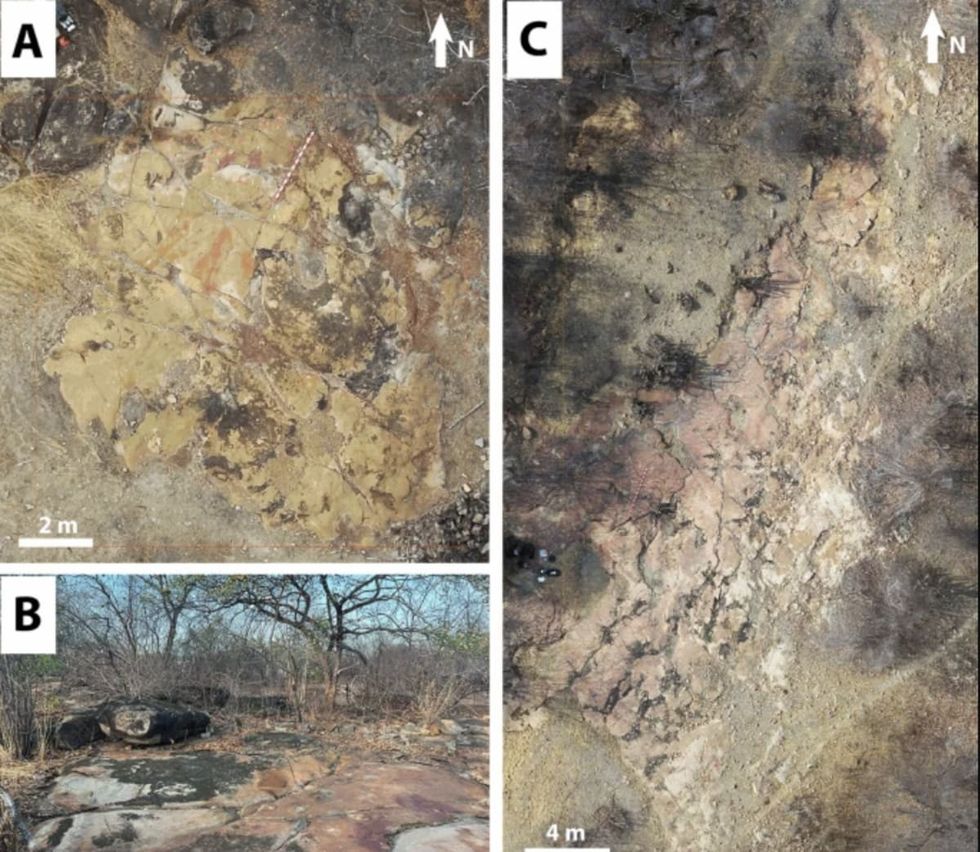

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:  Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

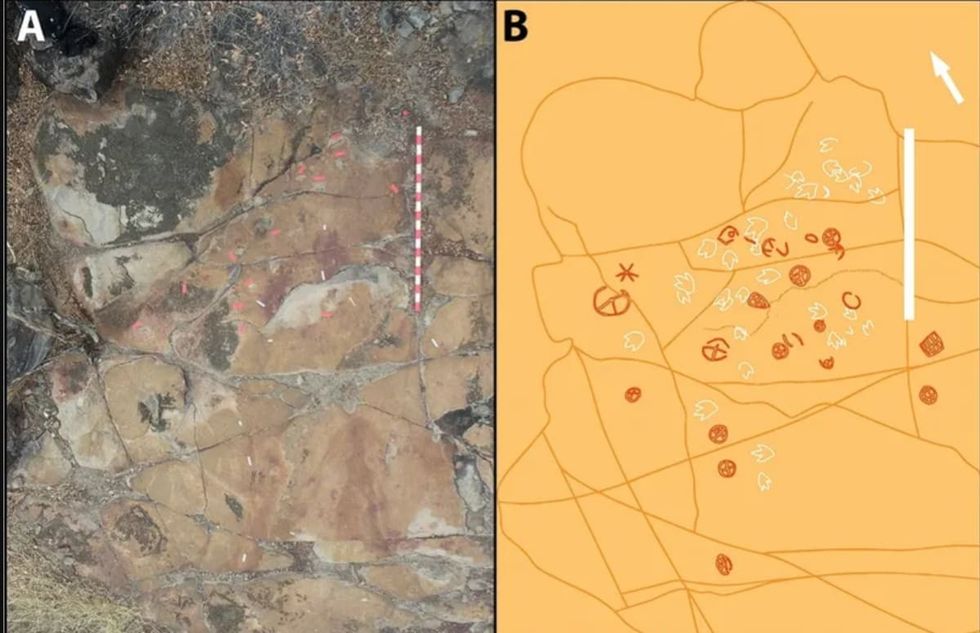

Image frmo Scientific Reports of ancient artwork.Image Source:

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

It's difficult to imagine seeing a color and not having the word for it. Canva

Sergei Krikalev in space.

Sergei Krikalev in space.

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The team also crafted their canoe using ancient methods and Stone Age-style tools. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo

The cedar dugout canoe crafted by the scientist team. National Museum of Nature and Science, Tokyo