You’ve probably heard a lot about charter schools lately, but you may not know exactly what they are, or what makes them so popular in some circles—and controversial in others. Now, with the proposed federal budget devoting $500 million in funding to charter expansion across the United States, you’re likely to hear even more about these publicly funded, independently operated campuses. And love them or leave them, charter schools’ unique status affords them the opportunity to function outside the traditonal educational model—offering a few key advantages.

Flexibility

The greatest is “the ability to have flexibility in curriculum, thus truly finding ways to teach material to all types of learners and levels,” says Kelley Reischauer, a parent of a sixth-grader at Valley Charter Elementary School and an eighth-grader at Valley Charter Middle School, which are both located in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley.

The nation’s nearly 7,000 charter schools have traditionally enjoyed broad autonomy over their budgets, curriculum, and staff. Reischauer’s school has a maximum of 22 kids per class in K-5, and each classroom has an instructional assistant, resulting in a 11-1 student-teacher ratio. Several studies have found that smaller class sizes, coupled with well-trained teachers, produce higher student achievement results. By comparison, Los Angeles Unified School District’s K-5 ratio is as low as 29.5-1 for kindergarten and as high as 39-1 for upper elementary classrooms.

Resources

Joe Tarantino, a ninth-grade English teacher at Hyde Leadership Charter School in the Bronx, New York, says there are more resources available at his school. “My charter school is much better resourced than any public school I previously worked for. This obviously presents a great opportunity for my students that students at public school might not get,” says Tarantino.

Tarantino’s 280-student, K-12 school, has larger class sizes—about 30 kids per room—but five building administrators, one for roughly every 56 kids, provide additional support. “When I first transitioned to charter schools, the most notable difference was how frequently I was observed,” says Tarantino. From a professional standpoint, he says the frequency of observation and feedback from administrators has made him a more effective educator, an experience supported by research from the Center for Public Education.

Tarantino is in his eighth year of teaching, and he’s spent the past three teaching at Hyde Leadership, his first charter school. “My salary is the same as a public school teacher of similar experience in the city,” he says. Hyde Leadership also ponies up the cash for Tarantino to attend professional development workshops and to stock his classroom with supplies. Along with ensuring teachers are supported, school funds are also channeled directly to students in the form of a school-issued laptop for every kid and up-to-date textbooks, says Tarantino.

Hands-On Learning

Valley Charter spends heavily on primary sources for project-based learning, which they believe leads to deeper understanding. “Instead of reading about the Chumash Indians and what their homes were like, and their way of life, the students build huts as they Chumash did, learn basket weaving, [and] make corn meal,” Reischauer says. Unlike most traditional public schools, Valley Charter also doesn’t contract with a textbook company; they only use textbooks for math classes. “The entire class is taught the same reading and writing strategies, which they can then apply to the [leveled] book they are reading,” Reischauer says. “My son has several visual perception disorders that greatly affect his reading ability. Were he in a school where he had to read the same book as everyone else, he would be so frustrated.”

Culture

Beyond the ability for their charter schools to control such details, both Reischauer and Tarantino say that charter schools emphasize building community. Outreach, interaction, and a strong, defined expectation of parent involvement are key aspects of their school culture.

“Throughout the year we have 10 family events, and parents must attend six of them,” says Tarantino. He says this creates a much higher rate of student attendance than he had experienced at his previous campus. “The combination of family, teacher, and student commitment is really strong here,” he says, adding that “a stronger bond with families means more accountability for me.”

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Simply being a charter does not mean a school will properly support student learning.[/quote]

Parents at Valley Charter are expected to contribute through volunteering and participation in school activities.“Teachers make themselves available before school, after school, and during lunch, as well as by email and Facetime after school,” says Reischauer.

Although Reischauer and Tarantino have each seen the benefits of their individual schools, they warn that simply being a charter does not mean a school will properly support student learning. Critics—including the NAACP, which last fall called for a moratorium on the privately operated, taxpayer-funded campuses—have voiced concerns about charter school accountability and the greater suspension and expulsion rates for black students. “It really depends on the nature and priorities of the school's governing board, competence of staff, faculty, and other adults, and student commitment,” says Tarantino.

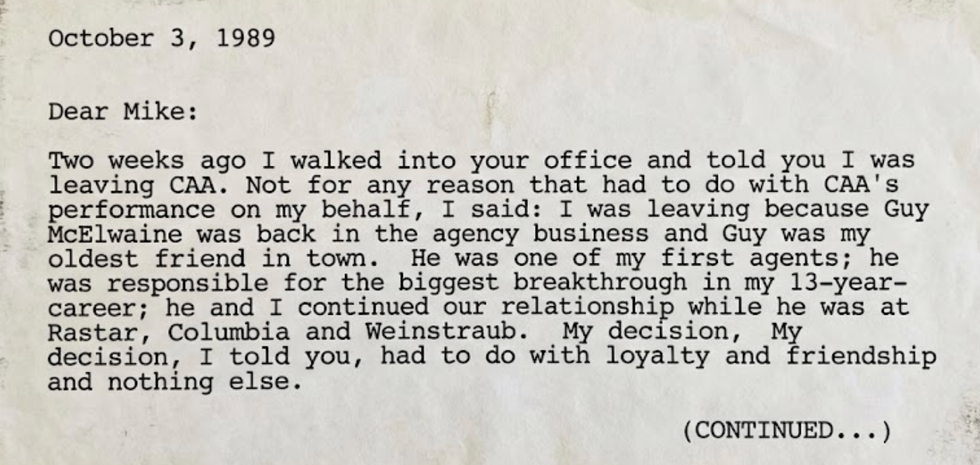

An excerpt of the faxCanva

An excerpt of the faxCanva

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit

Ladder leads out of darkness.Photo credit  Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit

Woman's reflection in shadow.Photo credit  Young woman frazzled.Photo credit

Young woman frazzled.Photo credit