Zachary Warren spends a lot of his time thinking about chairs. Desk chairs, to be more specific. Though there’s a range of chair sizes in the classroom where he’s taught for years in the Seattle Public School system, he says, “They don’t fit the kids. The desks don’t fit the kids.”

The problem, Warren believes, is that public education in his state isn’t fully-funded. Which means equipment doesn’t always work. Or adequate supplies simply aren’t available. So teachers like him — who already struggle to make it on salaries that are well below what it takes to live in the blazing Seattle housing market — must dig into their own pockets to pay for them. And when it comes to desk chairs, well, they aren’t exactly available for a couple bucks at the corner store.

Teachers being asked to foot the bill isn’t a pattern that’s limited to Washington; it’s a nationwide problem, due in large part to the fact that teachers, who are evaluated on student success, can’t do their jobs without basic supplies. But it’s surprising that in a prosperous state with a booming economy — home to two of the world’s biggest corporations, Amazon and Microsoft — schools can’t seem to put the coins together to pay for pencils and paste.

It’s a familiar conundrum for the Washington State legislature. Colloquially referred to as the WaLeg, the state government entered its second special session this month, an extension to the 2017 legislative period. Though the word “special” is right in the name, there’s nothing unique or surprising about the fact that lawmakers are staying in Olympia, the capitol, for an extra 30 days. It happens almost every year.

Despite the state’s reputation as a liberal haven, the WaLeg is split nearly dead in half down the aisle (the Senate has 24 Democrats and 25 Republicans, while the House has 50 Democrats and 48 Republicans). It’s a division that has led to some unusual funding shortfalls in one of the nation’s wealthiest states: Not a single one of Washington’s 13 resident billionaires pays a dime in taxes on their income or capital gains to the state.

For years, the WaLeg has engaged in a slow, expensive dance over taxes, revenue, and access to basic care, neglecting its single biggest responsibility along the way: funding basic education for every kid in the state.

Washington’s Paramount Duty

It’s not hyperbole to refer to public education as the state government’s most critical task — it’s literally written into the foundational documents. According to the preamble of Article IX of the Constitution of Washington State, “it is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.”

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]We have more tax breaks than any state other than New York.[/quote]

That language may not seem like it leaves much wiggle room, but the contention with what is “basic education” has been duked out in Washington Courts since the 1970s. After the Seattle Public Schools sued the State of Washington, a new act, the Basic Education Act of 1977, was passed defining what, exactly, the state is on the hook for.

Basic education was back in court 10 years ago, when, in 2007, a suit was filed against the state for letting the coffers run dry. In 2012, the State Supreme Court found that Washington State wasn’t meeting the criteria for “amply funding basic education.”

The court decision, McCleary v. State of Washington, has since become a rallying cry for education activists, tax reformers, and lawmakers looking to push their own agendas. And though McCleary makes an appearance in just about every stump speech for every seat in every city and county, there’s still been no solution.

Every year, lawmakers can’t agree on how to do it. Every budget session, they nearly approach a government shutdown over the matter. And every time, eventually, they find a way to patch up the budget just enough to hobble through another year; all the while, they’re firmly in contempt of court, being fined a ceremonial $100,000 per day, every day. The fines already total more than $67 million.

A Matter of Revenue

Given that Washington has defined the funding of basic education as the government’s most important job, one would think spending on education would be accordingly prioritized. But Summer Stinson, an attorney and board member of Washington’s Paramount Duty, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization of education crusaders who have lobbied the legislature to fix the gap, says it hasn’t yet.

“We have more tax breaks — 694, now — than any state other than New York. And yet, we’re the only one with a paramount duty to amply fund education,” she explains. “Some schools need a lot more money. Some only need a little more. But everyone needs some more.”

Stinson is citing the basic issue with Washington’s inability to fund schools — and the biggest sticking point in the legislature. With no income tax, a plethora of tax exemptions for the state’s many mammoth companies (Amazon, Boeing, Microsoft, plus several in biomed), and a business tax that’s basically flat, Washington’s revenue has been cascading over the last several decades, despite the state’s impressive growth.

Since the 1970s, Washington’s tax revenue has fallen 30% as a portion of state income; meanwhile, Seattle, the state’s biggest economic driver, adds close to 1,000 new residents every week. And those 13 billionaires living nearly tax-free — among them, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and Microsoft’s Bill Gates — boast a net worth totaling $180.3 billion. Meanwhile, Washingtonians pay “the fifth highest combined sales tax in the country.”

The result is the “most regressive tax system” in the United States. Washington’s poorer residents pay a larger portion of their income than those huge earners, and it’s a less balanced ratio than if they lived anywhere else.

How to fix that problem, though, has left Washington’s Democrats and Republicans locked at the horns (and the students, parents, and educators left in the lurch). The Washington State GOP has consistently advocated for “no new taxes,” says Stinson. “What it means, really, is while there might not be new taxes, there will be more taxes.”

In the budget submitted by Senate Republicans this year, no new taxes — such as an income tax, a capital gains tax, a head tax on large companies, or a carbon tax, all of which have been suggested by Democrats, including Governor Jay Inslee — would necessarily be added, but property taxes would be reworked and increased statewide.

That plan would be heavily reliant on a change to the way the state doles out levy money, though, which could potentially increase, not decrease, wealth disparities. In other words, the dollars and cents that everyone agrees are necessary also require some change that no one can seem to agree on.

A Patchwork of Funding Sources

Plenty of states struggle to fund their schools. Between the hyperfocus on standardized testing that the No Child Left Behind era ushered in, lawmakers intent on reducing spending at any cost, and increased interest in charter schools and privatization, cities and states are basically feeling between the couch cushions for change.

But unlike many states, which divvy up dollars solely using local property taxes, leaving a substantial wealth gap between poor schools and wealthier ones, Washington has attempted to equalize the education kids get. Unfortunately, that’s resulted in a race to the bottom that makes taxpayers bear the brunt.

One of the funding mechanisms that local jurisdictions can tap to help close the gap are levies. School districts can levy the property taxes in their area to drum up extra revenue, so long as the voters approve it. And, time and again, voters have. But thanks to a 1977 act, levies are limited in scope and capability, and they must be brought before the taxpayers over and over again to ensure schools have enough to get by. This leads to tax fatigue among constituents — and unnecessary spending on campaigns.

Additionally, a Constitutional amendment also approved by voters further limits the amount of property tax that the state can collect; schools can raise 28% of their total operating budget with levies, though that exists on a sort of sliding scale.

In an op-ed in the Spokesman-Review, school board member Neal Kirby described the issue:

“Inequities come about because school districts with a wealthier tax base collect far more per-student levy dollars with far lower tax rates than poorer districts. Seattle collected the 28 percent levy in 2015 for less than $1 per $1,000 of assessed valuation. Evergreen Public Schools would need $4.64 per $1,000, almost five times Seattle’s rate.”

In an effort to prevent the kind of access gap that funding through property taxes typically creates, Washington uses a levy equalization program. Through levy equalization, the state matches funds in some areas to ensure schools can pay for what they need. It’s a policy that’s designed “to mitigate the effect that above average property tax rates might have on the ability of a school district to raise local revenues to supplement the state's basic program of education,” according to state law.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]PTAs are the ‘dark money of education funding,’ removed from actual schools, operating much like a PAC.[/quote]

“These funds serve to equalize the property tax rates that individual taxpayers would pay for such levies and to provide tax relief to taxpayers in high tax rate school districts.”

In Kirby’s example, “Evergreen receives $16.3 million in levy equalization to address that inequity.”

Unfortunately, levy equalization has a fatal flaw: There’s simply not enough money in the pot to spread around. Despite the heavy reliance on property taxes to fund things in Washington, residents actually pay a rather modest amount compared to other states. Many rural and poorer school districts rely on this program — but it doesn’t necessarily limit the equity gap. Without more cash in general, it lowers the bar universally.

Rather than finding new revenue streams, Washington Republicans sought to ease the local burden by taxing property on a statewide level instead and eliminating the levy equalization package altogether. Critics of that plan include the Washington Education Association, who called it “a mishmash of bad policies that have nothing to do with ample funding — including lowering teacher standards, trampling due process and restricting collective bargaining rights.”

Real Impacts of Inaction

And while Washington lawmakers are arguing about levy swaps and property valuations, parents, students, and educators are trying — and have been trying — to handle the impacts of ever-dwindling resources.

Schools aren’t allowed to ask parents to directly buy items or pay for supplies for the school itself, but over the decade or more of decreasing resources, they’ve found PTAs to be a useful workaround.

These separate organizations, Stinson says, are “the dark money of education funding.” They are removed from the actual school itself and operate much like a PAC. Funds are raised by the PTA, which can then go forth and spend the money on gifts for the schools. Unfortunately, the “gifts” aren’t typically something special; most often, PTA money goes to desperately needed supplies, like printer paper.

A 2010 Seattle Times article found that with schools and districts tightening their belts, supplies like hand sanitizer and Ziploc bags were being added to supply lists; parents reported spending well over $100 at the beginning of the year. That was three years after McCleary was filed and two years before it was settled.

Unsurprisingly, educators are on the forefront of the decade-long fight to fully fund education. After collective bargaining efforts went south in 2015, Seattle teachers went on strike, citing the dramatic cuts they were expected to swallow, including the loss of services that directly benefit low-income and homeless students, as well as English language learners and kids in the foster care system.

Because, of course, the first services to be cut are those that affect the most vulnerable students.

School lunch programs are so strapped that students go into debt just for eating. Educator pay remains low, despite rising housing costs that ensure most teachers can’t actually afford to live where they work.

Programs and services that aid students with disabilities and other additional needs — ASL interpreters, mental health professionals, special education aides, and school nurses, who often offer the first line of defense when it comes to serious health issues — have been reduced to the bare minimum, leaving kids in the lurch and potentially setting them back for life. And it’s not just the special education kids affected by it either.

“I identify many of my students who need one-on-one support who just aren’t getting it,” says Warren. “It takes up so much more of your time. You start to plan your whole day around those students.”

Warren, who teaches at a fairly affluent school, says his students do have access to a counselor — who’s funded by the PTA — but that the resources are still so lean that it remains a constant challenge to ensure every child gets what they need.

“They Could Fix It If They Wanted To”

A decade after McCleary was first filed in court, lawmakers are still trying to figure out what to do about the problem. Kids who entered kindergarten when the suit was first brought are now studying for the SATs and applying for colleges in the same underfunded system.

Stinson doesn’t believe that funding education is an intractable issue, but she and many other advocates do believe that it’s an issue that isn’t taken seriously for a variety of reasons, including the perception that education is women’s work.

“Who’s volunteering? Women. Who’s writing to their representatives? Women. Who’s bringing in paper to their schools? Women,” she says. “Women are doing the work, but they’re not taken seriously.”

Crusading for education is, indeed, still largely seen as a special interest or a women’s issue. Most education reporters are still women, most of the individuals who show up to testify are women, and most of the people who are the most directly invested in the PTA are women, though many organizations are actively working to engage fathers.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Women are doing the work, but they’re not taken seriously.[/quote]

Of course, basic education and the welfare of children is everyone’s problem. If nothing else, it has massive implications for poverty, incarceration, and the tax burden down the road. Washington is also dealing with a massive and ever-growing homeless population. Additionally, a second state-run institution — Western State Hospital, which helps community members with mental illness — has been found in contempt of court.

These matters are not unrelated. It’s well-documented that poverty is cyclical and that failure to determine which kids have special needs at an early age leads to expulsions, higher dropout rates, and ultimately, less financial stability and success in adult life — particularly when students don’t graduate. As pointed out by The Seattle Times, “according to the Office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction, about 79 percent of Washington students in the class of 2016 graduated within four years. Nationally, the rate was 83 percent.”

Therein lies one of many difficulties with educational funding: It’s an investment — and one that many lawmakers won’t be able to reap the rewards of personally since by the time the children of the voters they represent are either eligible to graduate or not, many will be out of office. To solve the problem, elected officials have to ask for more money (specifically, from the donor class) with a very, very long-term ROI.

They’ve also been spooked by previous failures; an income tax measure that went before the voters in 2010 failed spectacularly, leading many lawmakers to view the idea itself as toxic. However, as the McCleary saga has dragged on, it’s become clear that something has to change, and voters have begun to express interest in this substantive solution.

The Seattle Times reports that, as of Wednesday, the WaLeg has reached a tentative deal, though details have yet to go public. “Fully funding education” has become one of the single biggest demands in legislative district meetings and town halls, and just about every person looking to keep their seat or snatch one up in the 2018 midterms will have to answer a question about how they’ll do it.

A young lion playing with an older animal

A young lion playing with an older animal A colorful bird appears to be yelling at it a friend

A colorful bird appears to be yelling at it a friend An otter appears like it's holding its face in shock

An otter appears like it's holding its face in shock Two young foxes playing in the wild

Two young foxes playing in the wild Two otters appear to be laughing together in the water

Two otters appear to be laughing together in the water A fish looks like it's afraid of the shark behind it

A fish looks like it's afraid of the shark behind it A bird appears to be ignoring their partner

A bird appears to be ignoring their partner A squirrel looks like it's trapped in a tree

A squirrel looks like it's trapped in a tree A bear holds hand over face, making it appear like it's exhausted

A bear holds hand over face, making it appear like it's exhausted A penguin looks like its trying to appear inconspicuous

A penguin looks like its trying to appear inconspicuous A young squirrel smells a flower

A young squirrel smells a flower An insect appears to be smiling and waving at the camera

An insect appears to be smiling and waving at the camera An otter lies on its side apparently cracking up laughing

An otter lies on its side apparently cracking up laughing Two monkeys caught procreating

Two monkeys caught procreating A young chimp relaxes with its hands behind its head

A young chimp relaxes with its hands behind its head A snowy owl appears to be smiling

A snowy owl appears to be smiling  A monkey holds finger to face as if it's lost in thought

A monkey holds finger to face as if it's lost in thought A turtle crossing the road under a 'slow' sign

A turtle crossing the road under a 'slow' sign A polar bear lies on its back like it's trying to hide

A polar bear lies on its back like it's trying to hide A rodent strikes human-like pose

A rodent strikes human-like pose

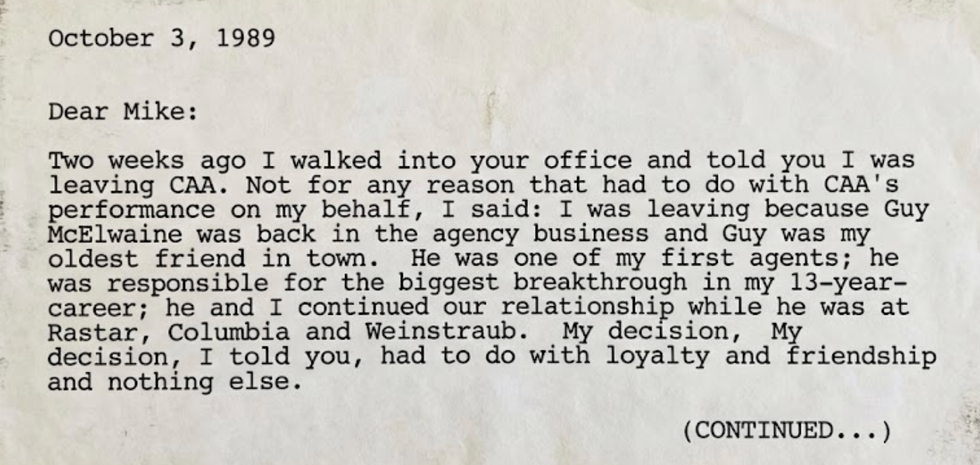

An excerpt of the faxCanva

An excerpt of the faxCanva

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Robert Redford advocating against the demolition of Santa Monica Pier while filming "The Sting" 1973

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation