The rules of “rock, paper, scissors (RPS)” are simple: rock beats scissors, scissors beat paper, and paper beats rock. Historically, people have played RPS to pass the time, settle disputes, or just for fun. According to Psychology Today, RPS dates back to ancient China, between 206 BC and 220 AD. While many once thought the game was purely based on chance, researchers from China’s Zhejiang University argued in a 2014 study that RPS is actually a “game of psychology.” By understanding this, players could develop strategies to improve their chances of winning.

RPS has been the subject of many mind game studies, which players in worldwide competitions and national leagues use to win the game. This 2014 study, led by Zhijian Wang, suggested that players of this game usually depict predictable patterns. Observing these patterns can enable a person to craft a unique strategy for their next move, that will make them win.

For the study, the researchers recruited 360 undergraduate and graduate students to play a total of 300 rounds of RPS, while their actions were recorded. In the experiment, Wang observed that winning players tended to stick to their winning strategy, while losers tended to switch to a new strategy. He called this process "persistent cyclic motions."

Here's how it works: As the game starts between Player A and Player B, both make random moves out of R, P, or S. As the game ends, by observing the move of the winner, the loser can optimize their next move. For instance, if Player A uses R and Player B uses S, Player A wins. For the next round, Player B can assume that Player A will use the same move, that is, R. This time, Player B can use P instead of S, thereby winning.

The gist is, that if a player won a round by playing R, they should play S next. If they won by S, they should play P next. If they won by P, they should play R next. On the flip side, if a player lost a round by playing R, they should play P next. If they lose by S, they should play P next. If they lost by P, they should play S next. Perhaps the most mathematically sound way to play the game is based on the concept of probability.

Notice that each move – R, P, or S, can beat one other move and can be beaten by the third move. So, it makes sense to pick paper one-third of the time, rock one-third of the time, and scissors one-third of the time. This is called the game's “Nash equilibrium,” per ABC News.

While the Nash equilibrium should be the best strategy for the players of the game, Wang challenged this theory by saying that it is also a lot about psychology and predictable cyclic flow. Instead of the notion that “player chooses three actions with equal probability,” these researchers said that the winners demonstrated what is called the “conditioned response.” “Whether conditional response is a basic decision-making mechanism of the human brain or just a consequence of more fundamental neural mechanisms is a challenging question for future studies,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.

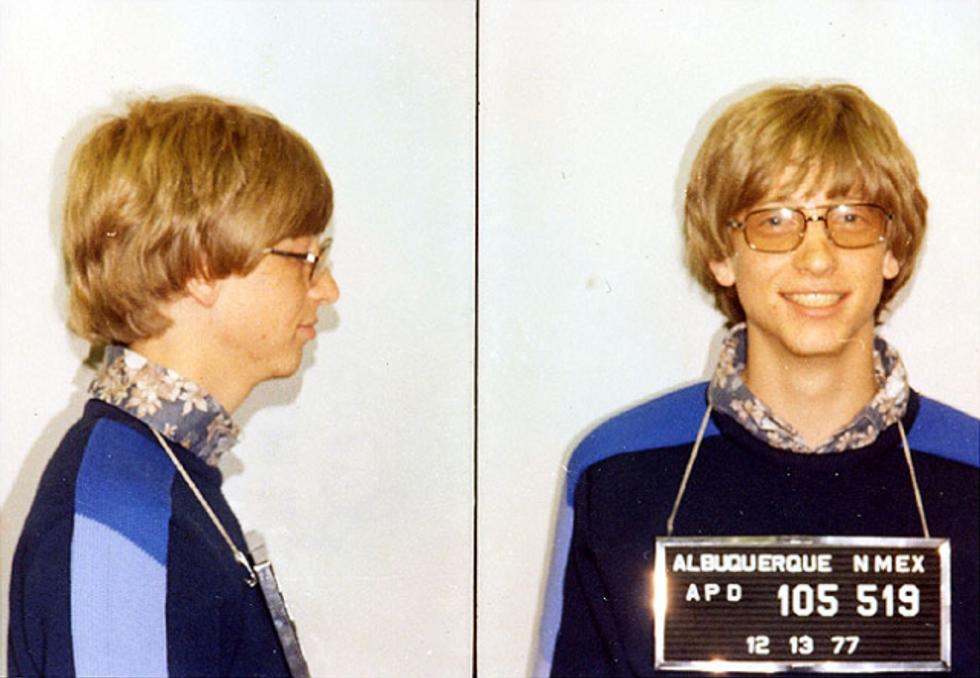

Bill Gates Swag GIF

Bill Gates Swag GIF File:Bill Gates mugshot.png - Wikipedia

File:Bill Gates mugshot.png - Wikipedia

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Enzo Varsi

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Enzo Varsi Representative Image Source: Pexels| Markus Spiske

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Markus Spiske Representative Image Source: Pexels| Nguyen Huy

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Nguyen Huy Representative Image Source: Pexels| Ana Benet

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Ana Benet

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anastasia Shuraeva

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anastasia Shuraeva Representative Image Source: Pexels | Liza Summer

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Liza Summer Representative Image Source: Pexels | Yankrukov

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Yankrukov Representative Image Source: Pexels | Shkrabaanthony

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Shkrabaanthony Image Source: TikTok |

Image Source: TikTok |  Image Source: TikTok |

Image Source: TikTok |

Woman standing in tree pose on edge of infinity pool (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | PhotoAlto/Sigrid Olsson)

Woman standing in tree pose on edge of infinity pool (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | PhotoAlto/Sigrid Olsson) Five adults practicing yoga, standing on one leg (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Thomas Northcut)

Five adults practicing yoga, standing on one leg (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Thomas Northcut) Elderly couple doing calf stretches in a park (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | RGStudio)

Elderly couple doing calf stretches in a park (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | RGStudio)

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Rene Terp

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Rene Terp Image Source: Instagram |

Image Source: Instagram |  Image Source: Instagram |

Image Source: Instagram |  Image Source: Instagram |

Image Source: Instagram |  Image Source: Instagram |

Image Source: Instagram |