On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which led to the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese-Americans. Often given less than 24 hours to leave their homes and farms with “only what they could carry,” families who lived in the newly defined “military zone” on the West coast were rounded up, forced to forfeit their property, and moved to camps with barbed wire and machine gun-armed guard towers overseen by the United States Army.

Plans were drawn up using guidelines for prisoners of war. The camps were spread across the most barren and hostile deserts and swamps of the country, with temperatures ranging from 30 degrees below zero to 120 degrees above.

“They were told they were going to these ‘pioneer communities’ because they were in danger from other Americans,” says Richard Reeves, journalist, historian, and author of the acclaimed book, Infamy, which offers a detailed historical account of the shocking brutality endured by Japanese-Americans during World War II. “But they did notice when they got to the camps that the machine guns were pointed in—not out—and the search lights were following them.”

This dark chapter in American history was later deemed unconstitutional—but the fear, propaganda, and racism that allowed it to happen in the first place may have come back to haunt us in 2017.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]We are a people of the present and future. We don’t look back very much.[/quote]

“We are a people of the present and future. We don’t look back very much,” says Reeves. “It’s one of our strengths—and one of our weaknesses.” Knowing our history with outsiders and those we’ve considered “dangerous” in the past, he became interested in studying the internment when he witnessed the hysteria that followed the attacks on September 11, 2001.

“If a few incidents of terrorism happen again, we could start to round up Muslims in great numbers as we did with the Japanese with no charges except for their religion, just as the Japanese had no charges except for the color of their skin—and they looked like the enemy,” said Reeves prophetically in April 2015.

Indeed, it was the San Bernardino terrorist attack in December 2015—in which 14 people were killed and 22 others were injured—that first prompted then-Presidential hopeful Donald Trump to propose what has become known as the Muslim ban.

Perhaps most frighteningly, Reeves says it was the some of the “best and the brightest and most revered of Americans” who knew about and approved the Japanese-American internment during World War II. Largely driven by wartime propaganda, the American public went along with the story they were being told by the nation’s highest office.

In that era of “fake news,” the media very much helped propel the racist narrative forward; there actually were plenty of salacious, editorialized, and factually inaccurate headlines in the nation’s top papers assisting the effort, according to Reeves.

Only a few reporters and editors throughout the country were willing to take a stand against the mass incarceration. One such newspaper was the Santa Ana Register (now the Orange County Register), whose publisher R.C. Hoiles wrote that “we should make every effort to correct the error as rapidly as possible” in October 1942.

“They knew it was unconstitutional and wrong, but it was popular,” says Reeves.

Actor and activist George Takei is perhaps the most famous victim of the widely praised law. He was only four years old when the knock came at his door.

“I can still remember that day when armed soldiers came to our home—soldiers with bayonets—they came to our home to order us out,” he told the Television Academy in an interview in 2011.

Takei and his family, like thousands of others, were sent to live temporarily at the Santa Anita race track in horse stables, which were fraught with disease. They were then sent to Arkansas, then to the Tule Lake camp in Northern California—one of the highest security camps—with three levels of barbed wire.

Committed to “never letting this happen again,” Takei has worked to educate politicians with a history lesson about what the internment was really like for Japanese-American families—two-thirds of whom were American citizens. His popular Broadway show Allegiance has given voice to the parents of the thousands of children like him who suffered in silence for decades. (On Febuary 19, Allegiance will be screened in select theaters across the country.)

Over the past few months, Takei has offered staunch warnings to President Trump on social media about avoiding the same path with Muslim Americans, though at the opening of a special exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles last week, he expressed hope to Southern California’s KPCC. Takei celebrated the reaction of thousands of Americans to President Trump’s Muslim ban.

"Immediately, massive crowds of Americans rushed to their airports, resisted, opposed the executive order. It is a different America today,” he said—more tolerant and more willing to speak up against atrocities.

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |  Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva A female artist in her studioCanva

A female artist in her studioCanva A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva

A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva  A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva

A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva  A woman flexes her bicepCanva

A woman flexes her bicepCanva  A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva

A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva  Two women console each otherCanva

Two women console each otherCanva  Two women talking to each otherCanva

Two women talking to each otherCanva  Two people having a lively conversationCanva

Two people having a lively conversationCanva  Two women embrace in a hugCanva

Two women embrace in a hugCanva

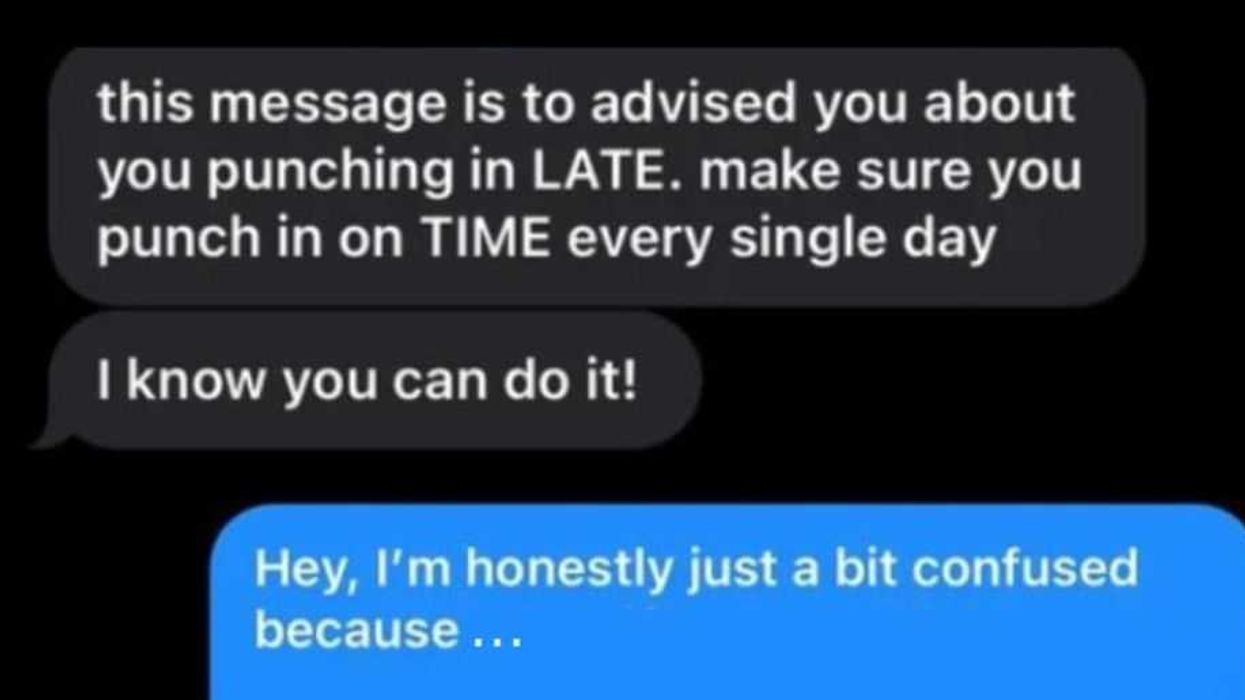

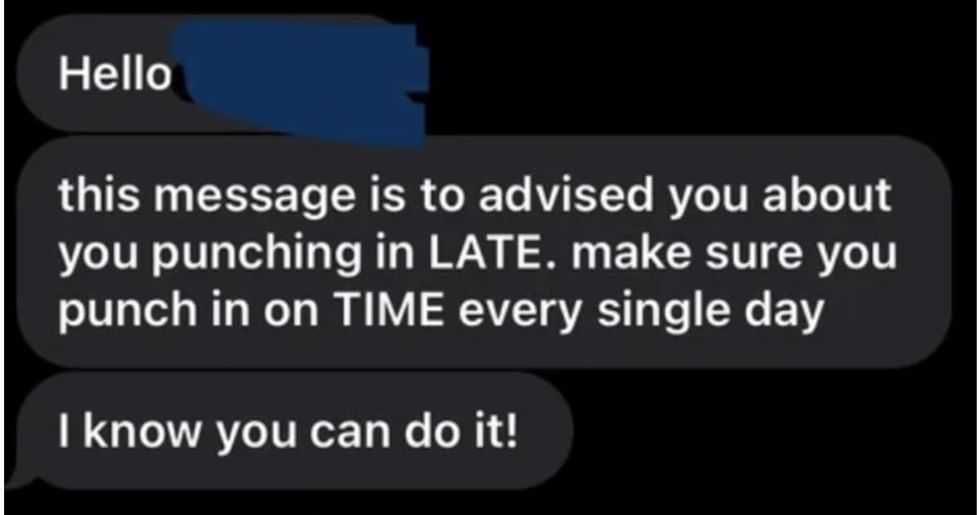

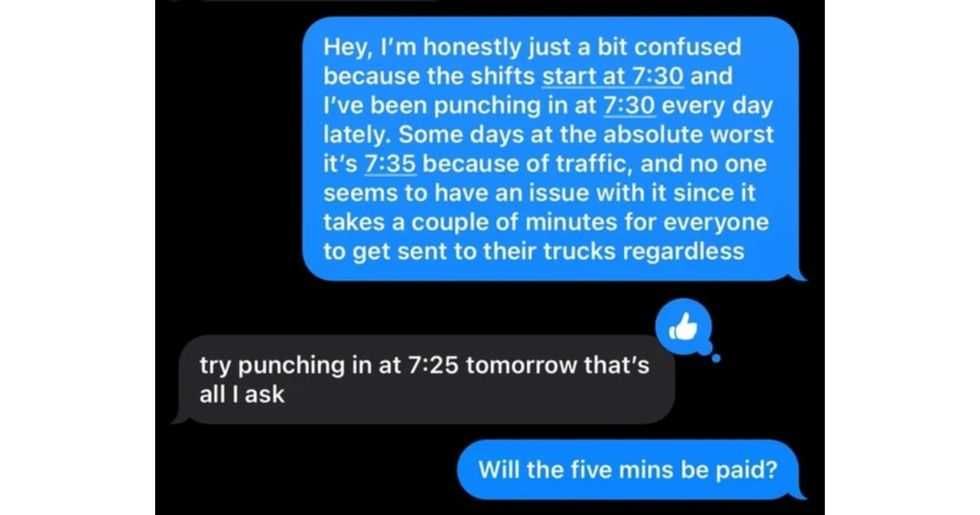

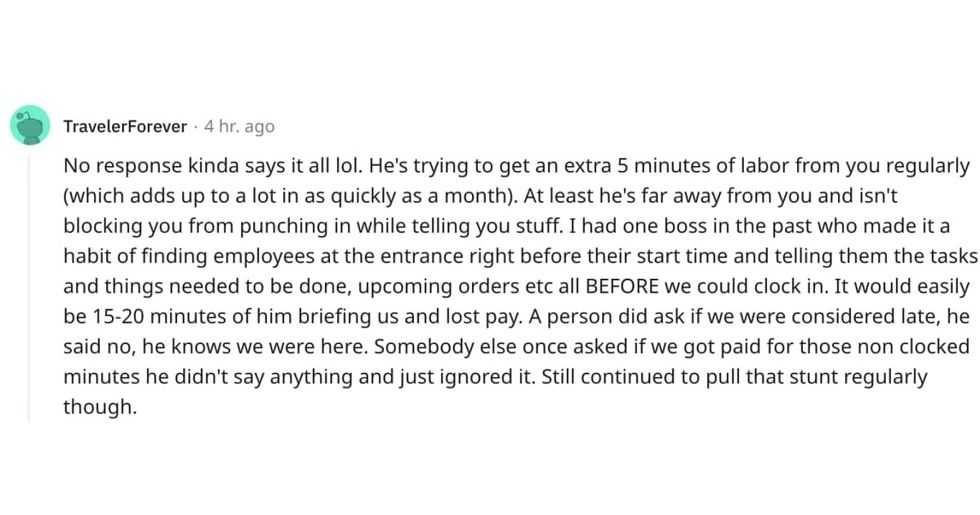

A reddit commentReddit |

A reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

A bartender makes a drinkCanva

A bartender makes a drinkCanva