Almost 25 years ago, I was learning to organize miners and peasants in the north of Chile. One of the movement’s leaders pulled me aside and handed me a worn copy of Comunidades Eclesiales de Base, a book by Leonardo Boff. “This is how to make it work,” he told me. A couple of years later, in a refugee camp in El Salvador, I got the same book as a gift. Since then, I have found Boff’s books on the shelves of human rights lawyers in Colombia, activist journalists in Mexico, and peasants trying to win land rights throughout Latin America. Boff, who spent most of his career as a Catholic priest, was both a spiritual and political leader, providing both moral weight and practical guidance to the fight against dictatorships and rapacious capitalism throughout Latin America’s most tumultuous years.

Boff left the small town of Concórdia, in the state of Santa Catarina where he was born to join the Franciscan Friars in 1959. Over the next 30 years, he organized “base communities,” small groups, spun off from the Brazilian church, to resist the dictatorship and strive for human rights. Writing about religion, community and politics, Boff became the most prolific scribe of liberation theology, a populist movement that questioned the church’s role in preserving a status quo rife with inequality and injustice. The poor and marginalized, he insisted, see power and suffering in a different way than the rich. Not that crazy an idea, considering the Bible is ostensibly a book about poor Judean peasants, carpenters, and fishermen.

Boff’s ideas and activism not only earned him the odium of the brutal Brazilian military dictatorship, but also of the Vatican. In 1985, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (the future Pope Benedict XVI) declared that Boff's ideas “endanger the doctrine of the faith” and officially silenced him, preventing him from writing or speaking publically for a year. In 1992, fed up and facing another censure, Boff left the clergy, feeling that he could do more for his people outside of the church. Boff continues to be an outspoken advocate for the poor and underrepresented as a writer, professor, and internationally renowned lecturer on theology and politics. He answered my questions from his home in Petropolis, in the mountains above Rio de Janeiro.

What is liberation theology?

In Latin America, the majority of people are both poor and Christian. Starting in the 1960s, religious leaders — both inside and outside the Church hierarchy — began to really listen to the cries of pain coming from workers, descendants of Africans, women, and other oppressed groups. Oppression demands liberation. How, then, could Christian faith contribute to the liberation of the oppressed? In the past, religion had served as a way to make people comfortable or submissive in an unjust world. But suddenly, people have the Bible in their hands, and they see that they are the heirs of a man who was imprisoned, tortured, and killed on the cross. Romans and religious authorities oppressed the people and killed Jesus of Nazareth, a man who tried to speak up for the poor. This basic insight is what inspired our Christian commitment to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and fight for liberation. Liberation theology approaches freedom from the point of view of oppressed people.

You did some of your most important work with the Church Base Communities. Can you explain what these communities are?

Base Communities actually emerge from a problem — there weren’t enough priests. Because of this, small groups of people came together to listen to Mass on the radio, or perhaps a sermon recorded on tape. Pretty soon, many of these groups gave up on the radio or the tape player, and started to read and talk about the Bible themselves. They sang and celebrated like a house church, and they divided all of the tasks of a church among themselves: Sunday school, liturgy, and community organization. Along with the trade unions, base communities became our own school of democracy, teaching us how to organize and govern ourselves. There are almost 100,000 of these communities in Brazil today, using the Bible to understand the reality of their day-to-day lives.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]The trademark of liberation theology is the preferential option for the poor, the struggle against poverty, in favor of life and social justice. Listen to the Pope, and you hear these ideas.[/quote]

How did these small groups of people involved in liberation theology oppose the military dictatorship in Brazil?

The people that were a part of liberation theology came from poor, marginalized groups and had come together to demand human rights. Because the church protected them to some degree, they had more freedom to act than many others; they wouldn’t immediately be taken prisoner or be disappeared. As international organizations, the churches had support from their European and North American counterparts. The dictatorship feared their international friends. Even so, many peasants fought for their land and were murdered. Many people were taken prisoner, tortured, killed. Other groups joined the armed revolution against the military dictatorship. The Church Base Communities were a kind of refuge for people who had been persecuted. They actively resisted the arbitrary violence of the terrorist state. They never knelt before the oppressor.

What do you think the movement’s future looks like?

As long as there is oppression, there will always be a theology that defends life and works for liberation. Now, with Pope Francis, we see a new strength: Francis sees himself within this theological current. The trademark of liberation theology is the preferential option for the poor, the struggle against poverty, in favor of life and social justice. Listen to the Pope, and you hear these ideas.

Do you think that Pope Francis opens the door to new liberation movements in the Catholic Church?

On Sept. 11, 2013, Pope Francis received Gustavo Gutiérrez, the founder of liberation theology, in a personal meeting. He also received Arturo Paoli, an Italian monk who is central to the movement. By doing this, Pope Francis is legitimizing a theology that has been persecuted by previous popes. This pope has made a great shift in the church: Instead of a fortress against the modern world, he sees it as a kind of field hospital, a common house, to which all are invited. The church-as-institution is no longer the center of his thinking, but rather, the People of God. In this case, “People of God” means the poor in the whole world, which is the central pastoral concern of this pope. After a long and dark winter, a flowering spring has broken out. I don’t see “Francis” as just a name, but as a project for the church and for the world: to be simpler, poorer, more brotherly, and more loving of nature.

Additional research by Rita de Cácia Oenning ds Silva

Ripe bananas

Ripe bananas How we treat produce could be changing for the better.

How we treat produce could be changing for the better.

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

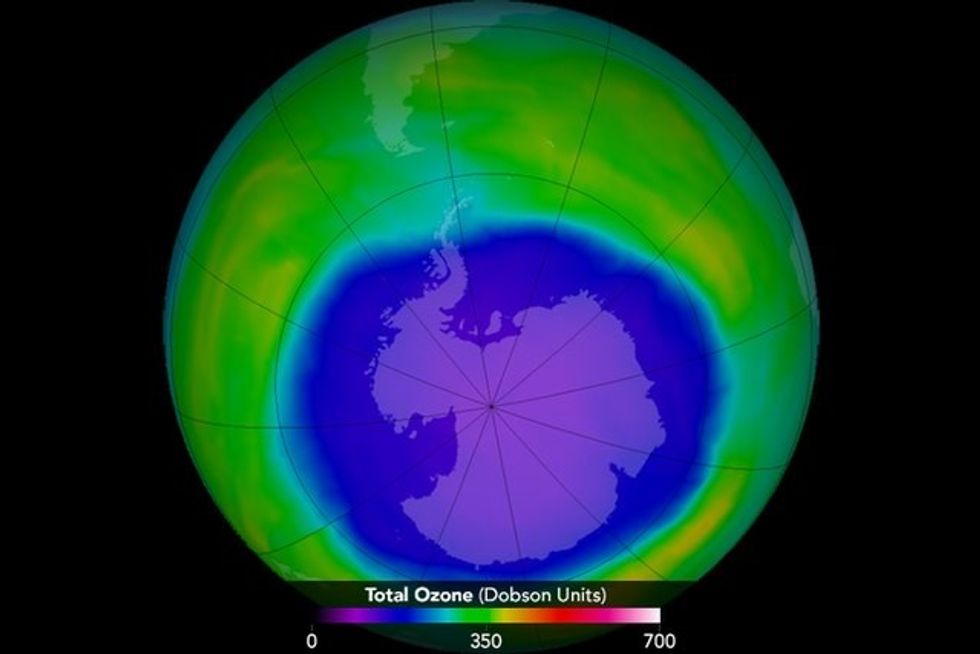

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva

In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva

Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva

Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva

Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn