British war reporter Christian Stephen has filmed conflicts inside Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. He’s been threatened by a cannibalistic warlord while on assignment in the Central African Republic, detained in Turkey, and, on several occasions, has stood a few hundred feet from the frontlines in battles against ISIS.

He also did it all before celebrating his 21st birthday.

Immersive journalism, particularly in conflict zones, isn’t new. However, Stephen brings an innovative approach to war reporting. In 2015, he traveled alone in Aleppo, Syria — at the time considered the most dangerous city on Earth — to film what is widely considered the first virtual reality documentary inside a war zone. “With VR coming in,” he says, “I wanted to use it for something important, rather than porn and video games.”

Much like a hardened soldier, Stephen has a pre-deployment routine. “First, I update my will and testament,” he says. Then, he obsessively researches his destination, calls fixers that will escort him through conflict zones, plots his travel routes based on ever-evolving battle positions, and sorts out his gear. He prepares essential items like video cameras, memory cards, and a bulletproof vest. He loads up his phone with songs from Queens of the Stone Age, Fidlar, and Everything Everything. Finally, he gets very drunk and reads a section of William Blake’s “Songs of Innocence and of Experience” on the way to the airport.

“When I get on the plane,” he says, “I’m dead already and I have to think that way.”

If that all sounds a bit melodramatic, it’s because Stephen’s life is filled with unfathomable adventures and the mental anguish that accompanies them. After all, virtual reality journalism is all about empathy — literally seeing the world through someone else’s eyes.

You and whose army?

In late 2017, Stephen embarked on his most ambitious VR assignment To Date. He returned to Iraq with co-director Celine Tricart to produce a film about a group of Yazidi women who had escaped from the clutches of ISIS and formed their own fighting troop to combat the extremist organization. “The Sun Ladies” premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, where Stephen once again found himself at the center of a discussion about the power and potential of VR filmmaking.

Publicly, it was a celebration of these incredibly brave women. Privately, it was both a continuation of the work he's been doing since he was a teenager, and it was a rebirth of sorts. It was only through telling the story of others who had escaped oppression and violence that Stephen was able to begin turning the page on a collection of traumatic experiences he had already assembled before he was legally old enough to rent a car.

Stephen’s journey to the frontlines in Iraq for “The Sun Ladies” wasn’t his first assignment in the region. In 2016, he found himself embedded with Iraqi federal police and Iraqi Special Operations Forces preparing to take back the city of Mosul from ISIS powers. He had gotten inside the group thanks to Davey Gibian, a Pennsylvania Quaker in his late 20s who works with non-governmental organizations as well as governments in troubled areas around the globe. Once the stock-in-trade of men and women with years of experience under their belt, the business of conflict journalism has increasingly fallen upon young people with little — or no — formal training.

Less than a year before, Gibian had helped Stephen sneak into Aleppo. Major news organizations had largely stopped sending journalists there, with dozens of media professionals killed over the past half-decade, including photographers and reporters from the U.K., France, Japan, and even Syria itself. Armed only with a Freedom 360 VR rig — six GoPro cameras mounted on a small tripod — Stephen shot a VR short film atop a bombed-out local building. With the Free Syrian Army covering his flank, the whole process took about two days.

The finished product takes viewers directly into the decimated city. You feel like you are there. The film would later become a huge success, landing Stephen a bit of journalistic fame and even an interview with Larry King.

Yet, what Stephen never publicly disclosed was that the direct aftermath of his Syrian shoot was a complete disaster, ending with him kidnapped and facing death. He only walked away alive after a brilliant stroke of luck that allowed Gibian to help rescue him. Other famous conflict journalists like Sebastian Junger have taken such episodes as a fateful warning sign and moved on to less dangerous work. Stephen isn’t oblivious to the perils, yet he continues to place himself in harm’s way.

A video clip from near Mosul shows Stephen running past ISIS gunfire, ducking into cover while filming Iraqi soldiers. It’s an undeniably alluring bit of performance art. War reporting is scary, dangerously addictive, and to the uninitiated, weirdly sexy. And for some, it’s also personally destructive. Even though Stephen walked away from that incident physically unscathed, the continued grind of war has ravaged Stephen’s psyche with the untreated effects of post-traumatic stress disorder. The horrible irony is that returning to conflict zones is often the only place where those living with PTSD can feel free of its existential toll even as they continue to tear open their mental wounds before they have a chance to fully heal.

Son of a preacher man

Stephen didn’t just walk into the world of conflict journalism. How he ended up a hardened veteran of war reporting is a story so surreal that it almost sounds scripted. His parents, Rory and Wendy Alec, are the founders of God TV, a televangelist network formed in the U.K. in 1994 and 1995, around the time Stephen was born. It claims to reach more than 200 million viewers around the world.

His father looks like a combination of Richard Branson and Steve Irwin, some kind of former 1980s rock star still brimming with ruthless determination and long, flowing blond hair. His mom, a former lounge singer with a blond mane of her own as well as a line of fantasy books, says she found Jesus after seeing his reflection in a bathroom mirror at a London nightclub.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]The reason I haven’t stopped is because I’m still seeking to bring a voice to those who have been ignored.[/quote]

God TV is where Stephen developed the skills that would eventually serve him out in the field. While most kids his age were playing soccer, he was serving as a de facto member of the crew on assignment in places like the Kondanani Children's Village near Blantyre in Malawi, documenting the plight of young children dying from AIDS. “I remember Christian being one of those kids who used to ask loads of questions,” says filmmaker Dan Woodrow, recalling trips to more than two dozen countries, including places like Zambia, Kenya, and Tanzania. “Me and the crew never looked at him as a young boy,” Woodrow says. “He was part of the team.”

Today, Stephen has a good relationship with his family, but before his 16th birthday, he quietly left home. Technically, he ran away. Yet he bristles at that description, saying it implies his parents either mistreated him or attempted to intervene. “The truth is, they barely even noticed until I called them from Mogadishu,” he says flatly.

“Although he can come across detached, Christian is deeply moved by authentic humanity,” his father, Rory, tells me. “I think he started this journey in an act of defiance, with a hint of rebellion and a little ‘I'll show you, Dad.’”

While in Jerusalem, Stephen stumbled into an early assignment. One night, he heard a riot on the Palestinian side of the border. The next morning, he borrowed a friend’s camera, and over the next few weeks, he started photographing and getting to know the kids who were throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails.

His first independent assignment officially began when Palestinian activists began rolling flaming dumpsters into the path of the Israel Defense Forces to create a smoke screen for their advancement. “Instead of leaning behind the corner with the other photographers, I thought it would be a good idea to get in the middle of this literal dumpster fire,” he says. Stephen says he wanted to breathe in the smoke, smell the burning trash, and fully immerse himself in the landscape as much as he wanted to sell photographs. “To be perfectly honest, I didn’t know enough to realize the inherent danger,” he says. As he ran past the flames, only pausing to capture images of the assault, several rubber bullets fired by the IDF cracked two of his ribs. “Because the adrenaline was running, I didn’t notice the pain until I got back to the Israeli side,” he says.

Later, a colleague connected him with Dylan Roberts, a journalism student in Arkansas. Together they formed Freelance Society, a production company for original stories from “the darkest and furthest reaches of the world.” Stephen’s first official assignment was bluffing his way into a trip with an NGO to Somalia. “I didn’t even know how to use the camera,” he says, with a dark laugh. “At the end of the trip, they found out I was not 25. I was, in fact, almost 17.”

Most people who see Stephen’s work have no idea how young he is, and he’s eager to avoid being seen as just some cocky kid with a camera gallivanting through extreme drop zones. “He’s always been the kind of person who has watched and adapted his personality and environment to fit in,” his sister, Samantha, tells me. “He’s an intelligent person and a wonderful person and very difficult for people not to be in awe of.”

He’s been traveling and shooting almost continuously ever since that first assignment in Somalia; his only downtime is when he impatiently waits for an NGO to hitch a ride with to the next assignment. In September 2014, at age 19, he chronicled the culture of child exploitation in Afghanistan nearly a year before The New York Times published its award-winning investigation. A rare stateside trip that fall took him to over a dozen Hawaiian brothels in one night, attempting to expose the sex trafficking trade that ensnares young girls from Thailand and the Philippines. In late May 2015, he traveled to Kathmandu, Nepal, following the massive earthquake that killed over 8,000 people. While there, he helped produce a short virtual reality film for RYOT that was narrated by Susan Sarandon. “I’ve never been homesick,” he says. “Coming from a nomadic lifestyle, you’re good at inserting yourself into every situation. And along the way, I accidentally started caring about my job.”

Dreams with sharp teeth

PTSD does not simply haunt those with grievous battlefield wounds; its crippling effects are just as often brought about from the trauma of witnessing horrific events. Stephen has seen a lot of trauma in his career, and it has had an impact on him as he struggles to live with a sometimes terrifying slideshow of memories.

Looking at dozens of photos of Stephen from the past few years traces a clear, dark progression. In a picture from 2013, he’s smiling; still so thin and childlike that his Kevlar vest hangs over his shoulders like an oversized school uniform. Less than two years later, his eyes appear hollow, his lips hooked in a jaded grin; a pale scar runs down the right side of his face; his lean, developed muscles filling out a frame that seems to always be carrying some combination of a camera, a cigarette, and a drink.

Some of that physical change is simply Stephen growing from a teenager into a young man, but to those who know him best, the expression he wears tells a darker story. “The core of him is the same, but his PTSD has changed him,” Samantha tells me. “I’ll tell you something even he doesn’t know: He’ll start screaming at 2 a.m. He doesn’t know it’s happening because he’s still asleep, dreaming.”

The first sign something had dislodged his psyche — the night terrors, emotional numbness, flashbacks, and creeping paranoia that every location was a potential attack site — came during a besieged reporting trip to the Peshmerga frontline in northern Iraq, just over a hundred feet from ISIS forces in the town of Sinjar. It was there that Stephen and his partner Roberts fell under heavy fire.

When they left the frontlines, Stephen and Roberts returned to their hotel for the evening. While his friend quickly drifted into a peaceful slumber, the night was just beginning for Stephen. “I basically woke up bolt upright,” he says. Stephen locked himself in the bathroom of his hotel room, slumped on the floor and began suffering the first of what would become severe and common panic attacks.

“I’m supposed to be the calm one in the group,” he says.

Stephen not long before that time had been introduced to the acclaimed war journalist Sebastian Junger through a mutual friend of Junger’s collaborator Tim Hetherington, a photojournalist who was killed while on a 2011 assignment in Libya. Sweating profusely, feeling like the walls were closing in on him and with one hand on his throat checking for a pulse, Stephen hammered out an email to Junger: “Everything I do feels like a copy of a copy. Like I'm the ghost of me somehow, just here to observe. Can't explain it.” Junger had given up war reporting after Hetherington’s death. He wrote a response to Stephen: “You're going to have to deal with this idea that you got away and that the universe is now owed a death — inevitably of an innocent person.”

Junger has been very public about his own experiences with PTSD, seeking to bring greater understanding to a condition that the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs says afflicts 11-20% of all Iraq veterans. “I told him how as war reporters, we risk becoming addicted to a certain image of ourselves as different from other people,” Junger tells me. “If there’s an addiction, it’s to the admiration that war reporting gets. That identity is the hardest thing to give up.”

The alluring call of danger is something Stephen knows all too well. So many of his former contemporaries, war reporters like Hetherington and Michael Hastings, are dead; one on the battlefield and other in a high-speed crash after returning home. And it doesn’t seem like Stephen is capable of walking away anytime soon.

“The reason I haven’t stopped is because I’m still seeking to bring a voice to those who have been ignored,” he says. “By making people feel less alone, I can prove to myself that I am not alone.”

No time to heal

Over the course of two years, I’ve kept in contact with Stephen. I caught up with him again recently while he was experiencing some rare downtime during an extended visit to Los Angeles. He’s exploring potential new projects while couch-surfing across the city, landing him everywhere from the Pacific Palisades to downtown L.A. among his seemingly endless stream of admirers and acquaintances.

Even in the sunny, laidback confines of the Santa Monica dive bar where we met to talk, it’s clear Stephen doesn’t have an off switch. When I walk in, he’s deeply immersed in a conversation with a fellow VR filmmaker, discussing the intricacies of their craft and personal details about their life stories. In the years since Stephen’s first virtual reality film, the VR industry has exploded in L.A. I ask the middle-aged stranger how long he’s known Stephen, and he says, “I just met him 10 minutes ago when I showed up and he said he was holding a seat at the bar for you.”

While he awaits his next assignment, Stephen grapples with his ever-present PTSD. He’s tried a number of approaches, including everything from recording himself reading children’s stories to looking into boxing classes at a local gym. He tells me he recently stopped drinking. Ultimately, the question is how much healing, both physically and mentally, he can string together before careening headlong back toward the abyss.

“In some ways, Christian had cloaked himself in a cocoon of cynicism and disappointment in people, and going to these dangerous destinations was a way to crack the numbness and ‘ping’ an emotional impact,” Stephen’s dad says.

Even though he's still only 23, an age when most people are finishing college and increasingly are moving back in with their parents, Stephen isn't sure how much longer he can be a conflict journalist. His face carries the ruggedly handsome weight of someone closer to 35 or 40 years old. He continues to produce groundbreaking work, but there are limits on how much psychological punishment he can put himself through, to say nothing of the appetite of a war-weary public. Yet, for all who think he should get out, just as many believe he should keep going.

“When people ask how he can keep doing this, I ask, how can he be the only one?” a former collaborator, Dan Woodrow, says. “If more people had the outlook on life that Christian does, I think we’d have a much better world.”

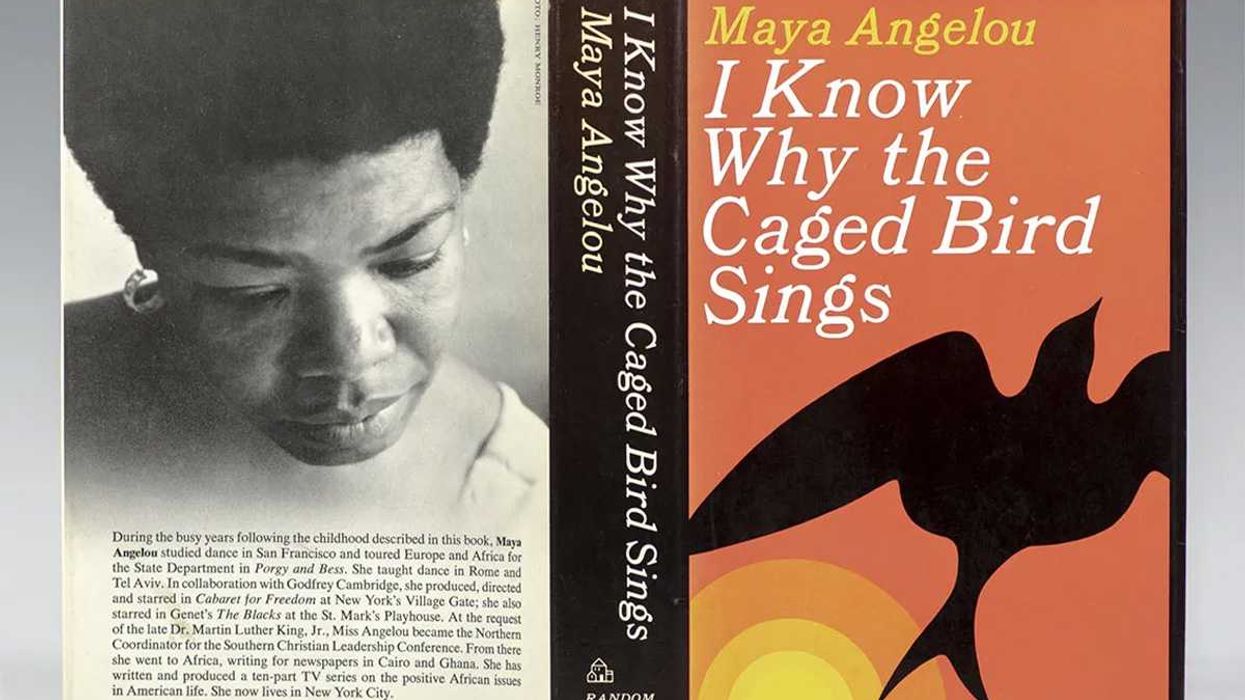

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/  First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva  Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva

Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva  A group of young people at a house partyCanva

A group of young people at a house partyCanva  Fed-up woman gif

Fed-up woman gif Police show up at a house party

Police show up at a house party

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva A reserved table at a restaurantCanva

A reserved table at a restaurantCanva Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva