Since its 1985 publication, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale has served as both warning and vindication to anyone with reproductive capabilities. When I read it for the first time as a young adult, the narrative seemed almost claustrophobically familiar, at once confirming my suspicions—yes, of course, here was the Republican Party’s demented fantasy, committed to text—and startling me into vigilance. Things could be so much worse, I thought back then. Indeed, that was where we lived: the precipice of So Much Worse.

Thirty-two years later, Hulu has adapted The Handmaid’s Tale as a miniseries, with Atwood’s enthusiastic blessing. The story has retained its relevance—and with the grinding persistence of patriarchy, how could it not? The Handmaid’s Tale imagines the United States as it exists in a postapocalyptic era, under a dictatorial regime of religious extremists. Fertility rates have plummeted, the upshot of environmental desecration. As a result, women who can reproduce are forced into sexual slavery as “handmaids”; they are assigned to the homes of wealthy infertile couples where they live under monastic conditions—save for once a month, when the head of the household has sex with his handmaid with the aim of impregnation. Stripped of their names, handmaids are identified by the first name of the men they serve, and in the context of ownership. For instance, our protagonist’s name is Offred, the simple union of preposition and proper noun: “of” and “Fred.”

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]I began watching The Handmaid’s Tale miniseries with the queasy pairing of excitement and apprehension. [/quote]

In the last year, as we witnessed the relentless ascent of a sexual predator to the country’s highest office, and our Congress swarmed with men who belittled women’s agency, Atwood’s imagined dystopia, the Republic of Gilead, loomed larger. We recognized the chilling parallels: reinvigorated crusades against reproductive rights like the Heartbeat Bill, transphobic legislation that shames and endangers the country’s “gender traitors” (Gilead terminology). And as Donald Trump and his administration began to run amuck in the White House, we braced ourselves, wondering to what extent this novel, a cautionary tale, would be inscribed as law. The answers, so far, have clamored with sickening vigor. Vice President Mike Pence broke a tie in the Senate in favor of defunding Planned Parenthood; subsequently, Trump supported that legislation. Marginalized communities—Muslims, blacks, Jews—are now at the mercy of a political regime that barely veils its contempt for them.

In the wake of these gruesome developments, we return to Atwood’s creation, seeking metaphors for the dreaded possibilities glutting the Trump Administration. Its images have acquired fresh meaning in today’s political climate—just last March, a group of women showed up to the Texas Senate Building dressed as Atwood’s handmaids to protest a series of antiabortion laws.

After ladling my own anxieties into the novel—long one of my favorites—I began to wonder if it would collapse, its meaning obliterated by the weight of my projections. For this reason, I began watching The Handmaid’s Tale miniseries with the queasy pairing of excitement and apprehension. In the shadow of a government eager to fashion its own dystopia, my mind seemed to breed handmaids.

Fortunately, series creator Bruce Miller seems to have anticipated my reservations and, in response, punctured the thin film between allegory and dramatic realism. Atwood’s reference to a military coup is amplified with explicit references to ISIS and the so-called war on terror. The book’s original setting, Cambridge, Massachusetts, gleams bright and lush. The handmaids are imprisoned amidst opulence and raped on verdant bedspreads. But past the regimented green lawns and the grocery stores, bodies dangle on a wall bordering the Charles River. State executions, and particularly their aftermath, serve as fear-mongering deterrents. Churches once revered as historical landmarks are unceremoniously leveled. In a flashback, Moira (Samira Wiley) is late meeting Offred (Elisabeth Moss)—explicitly named June in this adaptation—because her Uber is delayed. The city of Boston, an echo in Atwood’s novel, surrounds the characters like a skeleton scorched and picked clean. In Offred’s memories, the New England Aquarium (presumably) bathes her daughter in blue shadowed light. “Nothing we have shown you is impossible,” the series warns, “and the threat is nearer than you think.”

As our narrator, Moss’ Offred/June gives body to the rage simmering in our own stomachs without relinquishing her grace. She is irreverent and wry, her sorrows chiseled into resolve. Moreover, she’s funny, with a tendency to lob expletives in the face of trauma and horror. “I wish he’d hurry the fuck up,” she groans inwardly, while subjected to The Ceremony’s ritualized rape (this is the process by which the head of household has sex with his handmaid, as his wife sits above her, claiming the handmaid’s reproductive organs as her own). But of course, these glib remarks are anomalies, flickers of loosened nonchalance amidst taut, buzzing ire. Surrounded by her fellow handmaids in the supermarket, she scorns the fresh fruit that has excited the others. “I don’t need oranges,” her voiceover intones, as wrath just barely ripples her cadence. “I need to scream. I need to grab the nearest machine gun.”

The Commander’s wife, Serena Joy (Yvonne Strahovski) is depicted as much younger than Atwood’s character. In fact, her cold, gentile beauty bears an absurd resemblance to that of Ivanka Trump. They both wear their privilege pompously, like armor. But unlike Ivanka, Serena doesn’t attempt to obscure her complicity in Gilead’s brutal regime. She reduces Offred to a thing—“This is the new one,” she says when the latter arrives—and gossips within earshot about the handmaids’ supposed sluttiness.

In a way, her contempt is understandable. Presumably, the wives have little choice in this surrogacy arrangement. What’s more, Offred and Serena are positioned sharply as sexual rivals. The women are evidently close in age and, though Offred’s body is concealed, they are both conventionally attractive and blonde. As the most defenseless party, Offred only regards this perceived competition as a liability. Serena, however, resents her emotional vulnerability and spurns the possibility of Offred’s sympathy. From behind a corner, Offred watches as The Commander leads a gaggle of Gilead’s most powerful men past his wife and into a conference room. The camera lingers as the door shuts firmly before Serena, underscoring her own alienation from sovereignty. She turns to meet Offred’s softened gaze. “Go back to your room,” she demands.

Early in the novel, Atwood’s Offred tells her readers, “I would like to believe this is a story I’m telling …Then there will be an ending, to the story, and real life will come after it.” Perhaps the widespread reliance on this text indicates a similar desire. If we are living through our own Atwoodian dystopia, then perhaps we need only steel ourselves for four years or, better yet, until impeachment. But as the story indicates in both its forms, oppression never springs forth fully formed. We have lived with, even prospered from, its ingredients. And if we nod off—vigilance is, after all, wearying—we’ll awaken to a nightmare more lurid than we have yet imagined.

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

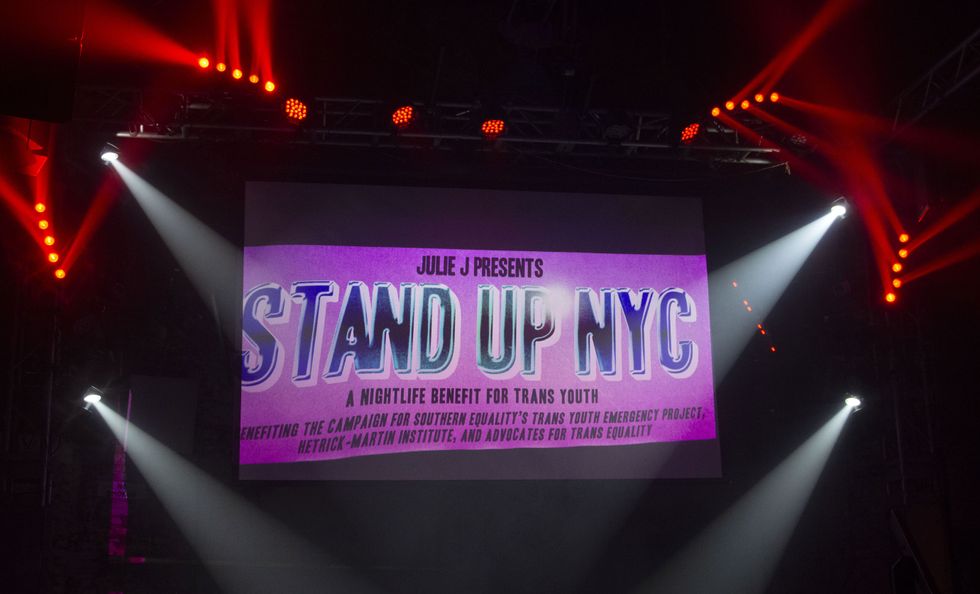

On March 30, Julie J gets organized in the DJ booth before Stand Up NYC begins at 3 Dollar Bill in Brooklyn. Elyssa Goodman

On March 30, Julie J gets organized in the DJ booth before Stand Up NYC begins at 3 Dollar Bill in Brooklyn. Elyssa Goodman Julie J in the DJ booth. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J in the DJ booth. Elyssa Goodman Julie J poses for pictures prior to the show's start. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J poses for pictures prior to the show's start. Elyssa Goodman Julie J at 3 Dollar Bill before Stand Up NYC begins.Elyssa Goodman

Julie J at 3 Dollar Bill before Stand Up NYC begins.Elyssa Goodman Julie J on stage co-hosting Stand Up NYC. Elyssa Goodman

Julie J on stage co-hosting Stand Up NYC. Elyssa Goodman