This July, the Dutch city of Rotterdam announced that it was considering a proposal to replace a stretch of its roads with what may become the world’s first all-plastic avenue. Proposed by KWS Infra, a subdivision of the Dutch firm VolkerWessels, the project, simply dubbed “PlasticRoad,” will use entirely recycled materials reclaimed from ocean dumps and incineration plants. The raw materials will then be used to create Lego-like building blocks, which the company claims may prove cheaper, easier to work with, and more durable than the asphalt used in existing boulevards. For the Rotterdam city council, PlasticRoad is just part of a broader climate initiative that includes and encourages innovative experimentation to help the densely populated Netherlands avoid undue pollution. If it takes off, KWS Infra’s project could revolutionize infrastructure across the world, simultaneously evening economic playing fields for developing nations and sparing the earth a huge chunk of pollution.

For many casual news readers, Rotterdam’s pending plastic road probably didn’t seem like such a big deal. After all, since plastics comprise up to a fifth of human waste by volume, we’ve been under pressure to develop new and innovative ways to recycle this near-immortal refuse for ages. In recent decades, we’ve managed to turn them into strong, lightweight, and cost-effective building materials (like polymeric timbers, used in many cheap modern tables and fences). Small, interlocking, and fully recycled plastic blocks have been on the mass construction market since the early 2000s, allowing almost anyone to incorporate such materials into their projects.

Over the past half-decade, especially, prefabbed plastic blocks have gone into vogue in home construction, where they’ve proven their merit again and again in increasingly public tests. By 2011, multiple companies had developed several variations on plastic bricks--some of which poured like concrete and others that stacked like it--often for use in low-cost and emergency housing. In China, Malaysia, and Taiwan, experimentation with these bricks proved that they cost up to 30 percent less than traditional construction materials, providing greater insulation, resiliency in the face of disasters, and reusability if a building was torn down. One company, angling to rebuilding housing in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, boasted that its plastic wall slabs could turn into a house in just 45 minutes using basic tools. These plastic barriers could outperform concrete walls, then break down into a foot-and-a-half-high stack for rapid construction, potentially accelerating the nation’s recovery and revolutionizing wider housing markets in the process.

Plastic bricks became so ubiquitous and accessible that they managed to become a part of the DIY movement around the same time, with people making model houses for hundreds of dollars, building their own plastic brick-creating presses, and trying to promote the technology as a grassroots and simple solution for poor communities to develop themselves. Given the scale of use, simplicity, and proven utility of recycled plastic materials, anyone with half a brain might expect that someone would have incorporated them into roads years ago.

Yet while people have long made things like manhole covers out of recycled plastics, it appears that no one had made a wholly plastic road. Many companies, especially out of India, had started adding shredded plastic to asphalt to help local roads withstand the wear and tear of erosion in the early 2000s. But even partially plastic asphalt only recently became cost-effective, possibly helping to limit experimentation in plastic road technologies versus other construction uses. If KWS Infra manages to move from partially to fully plastic roads, this won’t be just a minor win for an expanding construction technology. It will be a major breakthrough in attempts to control one of the most insidious forms of human pollution, waste, and urban decay.

The building and repair of roads produces up to 1.6 million tons of carbon dioxide per year, almost two percent of total emissions. That’s only likely to increase as urbanization and infrastructure projects, especially in the (rapidly) developing world, skyrocket demand for asphalt. Roads aren’t just a one-shot drain on the environment, either. Under the pressure of cars, expansion and compression of extreme temperatures, and erosive power of water, roads break apart within two or three decades on average (although they’re supposed to last 50 years). Repairs and resilient additives are often expensive, meaning that roads usually decay for years, unfixed, causing polluting traffic and significant immediate risks to human life via collapse. Then in the end, they just have to be replaced entirely, compounding the pollution and waste of each new foot laid (by many times).

But, according to KWS Infra, recycled plastic materials have proven up to three times more durable than asphalt. They should be able to withstand temperatures from -40 to 176 degrees Fahrenheit without cracking, preventing erosion. Instead--as the roads will be hollow--they will provide space for safe water retention. All told, this should allow a plastic road to last three times as long as a normal road (surviving 50 years at least rather than at the outside). Since the roads will be constructed out of pre-existing plastics, their construction will put far less carbon into the air than asphalt and require less polluting maintenance in the long run. As they can be recycled again into a new road when they break down, the environmental cost of replacing them will be minimal. In the end, the technology could potentially eliminate the bulk of a major source of pollution.

KWS Infra’s plastic roads will be far lighter than asphalt, which means it will require less energy to transport and install. (There’ll be no need to lay a foundation of concrete over soft land, for instance.) This, plus the interlocking and prefabricated nature of the road, means it should only take weeks to install a new avenue, rather than months, and use less complicated tools. The same hollowness that helps to make them light will also make it easier to install fiber-optic cables, sewage mains, and other complementary pieces of infrastructure. This can even include high-tech road apparatuses, like heating blocks to prevent icing or load monitors to better record traffic data.

This ease of construction isn’t just a bonus for Dutch developers; it’s potentially a great equalizer for developing nations, for whom costly and time-consuming infrastructure projects are a necessary but slow-moving headache, holding back wider economic development. The ability to rapidly lay a road without pouring a foundation or leaning on excessive expertise, all on the cheap, with openings built into the prefabbed blocks for sewage or IT connections, could allow these struggling nations to rapidly accelerate the construction of new economic corridors, giving a swift and powerful boost to the development of their local economies and national wellbeing.

Unfortunately KWS Infra’s technology isn’t ready for the mass market yet. PlasticRoad is still in its conceptual infancy. The firm stresses that it needs to test the technique in a lab to make sure, among other things, that the surface won’t prove slippery when wet--and that it will be able to deliver on all of these awesome claims of environmental benefit and ease of assembly. Plus they still need to find partners in the recycling sector to provide them with the proper plastic excess.

Still, the firm’s confident that they’ll be able to start their experiment in Rotterdam within three years. The city’s already got a bicycle path in mind as a testing ground, and other cities have expressed interest in their technology as well. While KWS Infra has all of the backing and resources it needs to move forward, it’d be ill advised to hold our breath waiting for PlasticRoad rather than exploring other ways to cut down on asphalt pollution and help developing nations with infrastructural development. But the success of other plastic building materials and the positive reception to PlasticRoad in Rotterdam and elsewhere suggests that the project has a real chance of succeeding. And if it does, the fruits of the project could be phenomenal.

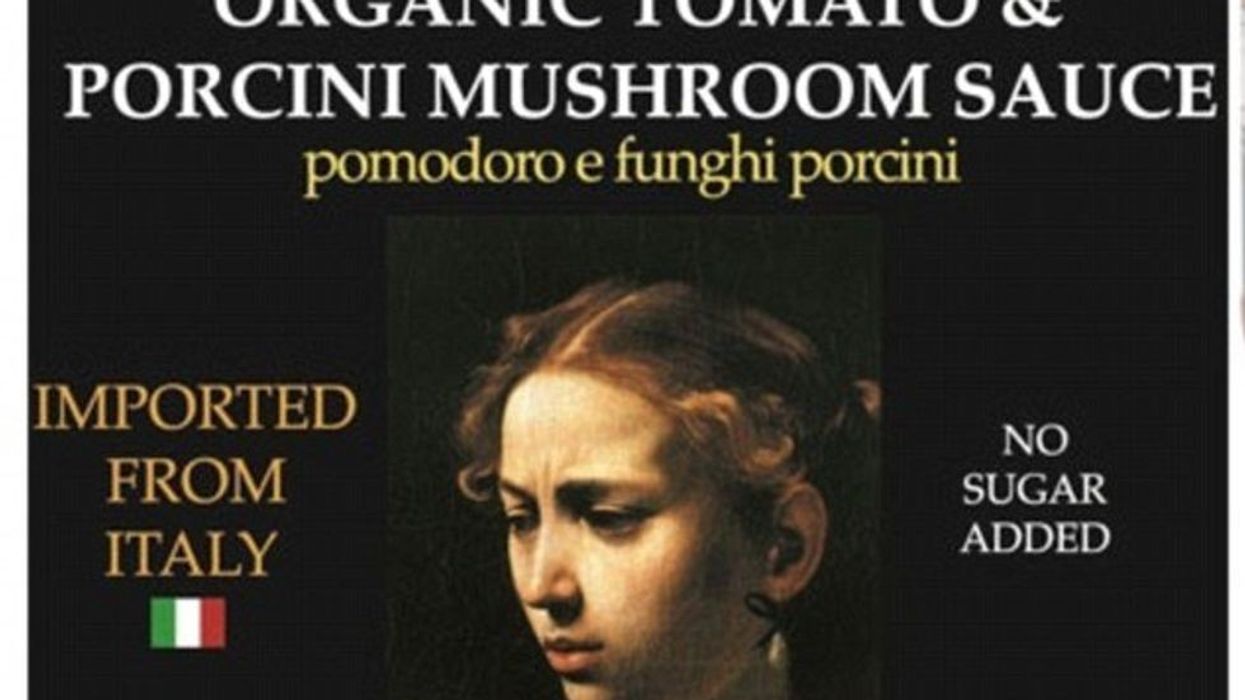

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)