Artist Serge Attukwei Clottey gestures around the cramped back room of his workshop in Accra, Ghana. Intricate lattice sheaths litter the space: the ones rolled up on the floor are mostly yellow and red tangles of plastic; the stringy matrix hanging by the door is a black mesh of interwoven rubber. What others consider useless scraps, Attukwei sees as a bevy of supplies. “My materials are what society has left behind, what people see as discarded,” he says. “The process I put it through isn’t recycling. But I change the function. It becomes valuable.”

The journey from garbage to gallery piece is central to the overarching narrative of Attukwei’s art, in part because his own ancestral story is one rife with voyages. In the past, he says, the Clottey clan was known to travel to the northern part of Ghana and return to the coast with voodoo. When the chief of Labadi, now one of Accra’s renowned beach towns, needed to be spiritually fortified for an impending skirmish against a rival township, it was the Clotteys’ mysticism he called upon. In return, they were rewarded with land—from Attukwei’s studio located on Labadi Beach Road, minutes from the water’s edge, to the oceanfront. “That is how we migrated here,” he says.

The name of one of his great-great grandfathers, Nii Tetteh Nteni, hangs above an awning in Attukwei’s studio space like an incantation. “My ancestors sold alcohol and meat to the people of Labadi,” he continues, recalling his seafaring family history, pointing out that “Nteni” signifies “liquor” in the Ga language of the coastal people of Ghana. “When they got to the shore, they transported the alcohol with these plastic gallons.”

The gallons to which he refers are the ubiquitous yellow gallon containers, or jerrycans, found all over Ghana. “These are imported oil containers. When they get here, we pour the oil out and, after, use the container for something else.” To Attukwei and the citizens of Ghana, they are stark reminders of Africa’s lopsided trade relationship with the West. And as the country’s fortunes improve and even the poorest homes acquire indoor plumbing, the yellow cans are outstaying their welcome. “Plastic has a long life span. How do we deal with that?” Attukwei asks, pointing out the massive environmental implications of the cans. For him, the omnipresent yellow plastic became a canvas to be drilled, stitched, and painted upon, hacking the jerrycans to craft conceptual masks and large-scale art installations conspicuously staged in Accra’s public spaces.

Resettlement, relocation, and repatriation: Attukwei obsesses over these themes because he has seen the difference even a slight change of course can make. As a child, his father, himself a painter, enrolled Attukwei in art school while simultaneously trying to discourage his son’s interest in electronics. “I would play with toys meant for little white children. I got interested in playing with gadgets, fixing broken radios, trying to understand how things were built,” he remembers. “My dad told me that I was a black boy and I could not invent. I should just do art—draw nicely, sell, and make money.”

But that explanation didn’t satisfy Attukwei. At some point, he combined his interests, creating art installations that incorporated light and sound. His father rebuffed his mixed media experimentation, as did a number of local galleries, but Attukwei continued to labor. This refusal to accept restrictive norms has come to be characteristic of his resilient spirit and dedication to exploring what resonates with him, both as a citizen and as an artist.

To that, public participation has become fundamental to Attukwei’s work. He founded the GoLokal performance art collective in Ghana, hoping to bring art closer to the people and, most importantly, promote community development. In 2012, during the country’s elections, GoLokal carried out a particularly pointed performance as political commentary—well-dressed participants acting as wealthy politicians dragging a bound Attukwei through the streets by a noose, a sign saying “YOUTH” hanging around his chest. National news sources played the footage on their broadcasts for a week.

“When I first [moved to Labadi], I was doing my art in private,” Attukwei says. “After my performances started being aired on television, people began approaching me, asking if they could participate.” Not only was he encouraging his community, showing them that they could have a very public voice in a national arena, but his process benefited as well. Now, Attukwei employs a team of five eager young men who help bring his visions to life, remarking that “[the guys] make the production easier. Now, I can take a week to create a huge piece.”

Even the process his team undertakes for each piece has became a performance in itself. “We go to dump sites and buy the gallons. Then we transport them to the studio on our backs. We don’t use cars.” Attukwei enjoys enthralling and involving people on the streets by turning even mundane tasks into a spectacle.

It all fits into his Afrofuturist statement of intent: “Afrogallonism”. Through art, he argues, the faulty economic relationship between Africa and the West can be upended. “Afrogallonism is about pushing back to the West what they left behind,” Attukwei says. Fittingly, the creations Attukwei is currently making explore this very idea, and will be on display for his upcoming solo exhibition at recently-opened dual galleries Feuer/Mesler and Mesler/Feuer in New York. And while he’s excited for his show in the U.S., he remains committed to making sure his work and the dialogue he’s seeking to provoke are present outside the more exclusive world of art galleries and private collections. For Attukwei, the art should be about the people, and for the people.

“It’s a cycle: It comes as an oil container, I turn it into art. It goes back and serves a different purpose. Then, we benefit.”

A hotel clerk greets a guestCanva

A hotel clerk greets a guestCanva Gif of Faye Dunaway' as Joan Crawford demanding respect via

Gif of Faye Dunaway' as Joan Crawford demanding respect via  An empty rooftopCanva

An empty rooftopCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva Waves crash against rocksCanva

Waves crash against rocksCanva

Two people study a mapCanva

Two people study a mapCanva Foggy Chinese villageCanva

Foggy Chinese villageCanva

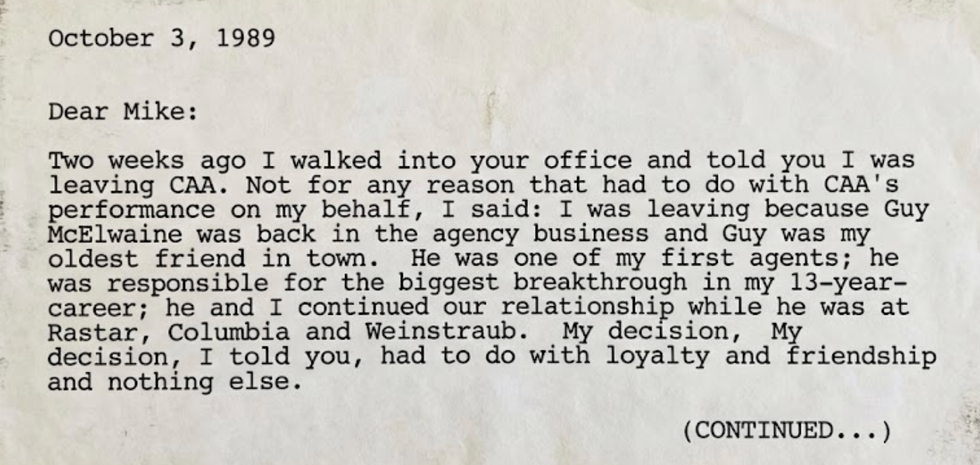

An excerpt of the faxCanva

An excerpt of the faxCanva