“People give me bones,” Asha de Vos says, dwarfed in the shadow of an 87-foot blue whale skeleton on display at the Seymour Marine Discovery Center in Santa Cruz, California. A few yards away, cliffs overlook Monterey Bay as the Sri Lankan marine biologist shares one of her pet dreams: a garden featuring whale vertebrae refashioned as stools. She already owns several.

For the past two years, de Vos has worked as a post-doctoral scholar at the University of California, Santa Cruz’s Long Marine Laboratory, assessing the risks of proposals to protect Sri Lanka’s blue whales, commonly killed by commercial ships. Though the Colombo native has studied the species for more than a decade, she still looks upon Earth’s largest animal with wonder. “It gives you a sense of scale, makes you realize how small you are,” de Vos says. “It also makes you realize we created the only thing that can kill it.”

De Vos’ relationship with what she calls Sri Lanka’s “Unorthodox Whale”—the only known nonmigratory blue whale population, living in one of the world’s busiest international shipping lanes—started in 2003. After earning her undergraduate degree in marine and environmental biology, she was living out of her car in New Zealand, researching Hector’s dolphins and writing letter after letter to a whale research vessel run by Roger Payne, the man who discovered humpback whale songs. Months of begging eventually earned de Vos a deckhand gig; she joined the crew in the Maldives, polishing brass and cleaning toilets.

While on watch duty off the southeast coast of Sri Lanka, where the team was tracking sperm whales, de Vos noticed a “tall, lofty blow” from the water. She was surprised: Sperm whales have only one nostril, so their blow veers to the left. She called the captain, and as the ship moved closer, the crew realized six blue whales were swimming in an area the size of a football pitch. It wasn’t a stretch, since blue whales mate in warm waters, but they weren’t breeding or calving. They were pooping.

“First of all, blue whale poop is red,” says de Vos, leaning forward excitedly. “So that’s sort of epic. Oh my god, it’s so beautiful. Second of all, it told me they were feeding.” It was the first blue whale colony ever observed feeding in tropical waters.

After earning her master’s at Oxford, de Vos returned home after the 2004 tsunami to work for a local marine conservation organization, and in 2008, as Sri Lanka’s 25-year-long civil war wound down, she entered one of the country’s newest industries: whale watching. Boats would invite de Vos on board to answer tourists’ questions in exchange for letting her track blue whales’ locations. She used that data in her Ph.D. work, building habitat models to study the physical conditions that made the Unorthodox Whale population possible.

Now armed with the research from her stint in Santa Cruz to formulate hard recommendations—like proposing that the Sri Lankan shipping lane be shifted 15 nautical miles south—to the International Maritime Organization, de Vos recently moved home and is preparing to launch a new venture. OceanSwell, an educational organization that’s developing graduate school curriculum, immersive adventure programs, and documentaries, aims to help Sri Lankans control the marine conservation conversation.

“I want to make Sri Lanka a landmark of marine sustainability in the developing world,” de Vos says. “That’s my dream.”

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

Big Brain GIF by Jay Sprogell

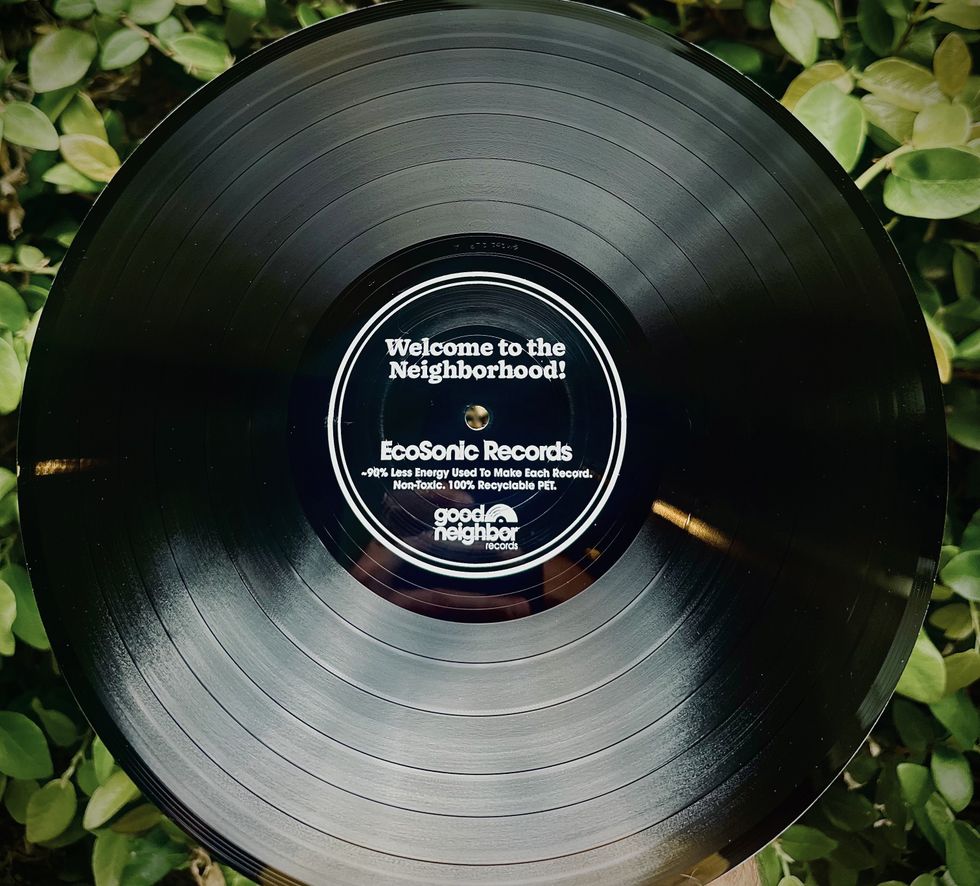

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor record.Photo credit: Good Neighbor Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Photo credit: Good Neighbor Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor

Good Neighbor Records are green.Photo credit: Good Neighbor