Fatana Hassanzada was only 16 years old when she first appeared as a television news presenter in Afghanistan.

In her hometown of Mazar-i-Sharif, working in the media was a nearly impossible dream for a woman, let alone a young girl her age. It was 2009, and the Taliban were no longer in control of the country, but they still held power in some regions. A small movement to progress beyond their ideological control had begun, and some women were beginning new lives in the workforce.

Today Hassanzada is 25, and she is revolutionizing how women are seen in her country. She is the editor-in-chief of the region’s first lifestyle publication, a Vogue-like magazine for women called Gellara. For a country like Afghanistan — where women were not allowed to leave their homes only 17 years ago and girls were banned from schools — women’s media is a novelty.

But Hassanzada is not alone.

There is somewhat of a silent uprising among women in the country, who are strategically maneuvering their way to be heard and to become more visible. Using the platforms of media and journalism, which are considered radical to some people in the country, Afghan women are breaking free from past social and cultural shackles. Through magazines and even women-run television stations, they’re stepping up to become women and journalists in a place that has shown hostility to both.

Hassanzada experienced that hostility firsthand.

When Hassanzada’s image on television was broadcast across the nation at age 16, the Taliban became angry, and their warlords in her neighborhood expressed fury. Hassanzada started getting threats and warnings by the warlords and from her neighborhood elders.

But she kept going back to work and never stopped.

A tenth-grader like her could seem too young to have such valor, but girls in Afghanistan are forced to grow up fast. Hassanzada’s family showed her support, even though the Taliban’s warnings affected them too. Her family was bombarded with threatening letters, phone calls, and physical bullying.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]We are entering the age where women will continue to dissent in Afghanistan.[/quote]

Hassanzada knew if she ducked from these intimidations, it would discourage all Afghan women who were watching her career on television. If she quit, the Taliban ideology she opposed would continue to thrive. “If we quit every time we are threatened or attacked, then women would never get anywhere. We have to be fearless,” Hassanzada says. So she continued to take the risk — until tragedy struck.

One day in 2011, her brother was attacked and gravely injured by Taliban thugs who wanted her to leave her TV job.

The threats never stopped. For a while after the attack on her brother, Hassanzada had to stop working and her family had to move to Kabul to be safer. They were subject to all this danger just because she was a woman. “Simply that, can you imagine how outrageous that is?” Hassanzada says. What enraged her more, though, was how women were complacent to being treated like prisoners even after the Taliban were no longer in power. She wanted to encourage other girls and women to pursue their dreams like she had.

She decided to continue her work in the media. In 2017, she achieved her own dream of starting a publication that would not only educate and entertain women, but employ them too. In May 2017, the first copies of Gellara went to the presses. Today her magazine, created by an all-female, mostly volunteer staff, hits the newsstands every month, addressing topics ranging from breast cancer awareness to Tinder.

Hassanzada’s courage to persevere seems close to that of the Nobel Laureate Malala Yusufzai, who was shot by the Taliban in Swat, Pakistan, just a few years after Hassanzada’s brother was attacked in Mazar-i-Sharif. It is hard to overlook the intrepidity and fearlessness of young girls in this region who have stood up to the Taliban ideology and — in many ways — defeated it.

“We are entering the age where women will continue to dissent in Afghanistan,” Hassanzada says. She hopes her work can resuscitate her country’s conscience and help in improving the equal status women ought to have.

While Hassanzada was one of the first women to publicly display radical hope for the future of Afghan women in the media, many other women are taking action too.

An all-women-run channel called Zan TV launched around the time Gellara debuted. “Women produce, women do the scripts, women direct, and women present all the content,” says the founding director, Hamid Samar, who launched the channel in 2017 on a shoestring budget. Samar plays a major role in helping women and their work demonstrate a new vision for all women of Afghanistan.

Zan TV has an entirely female staff featuring more than 50 young women anchors and producers, many of whom come with incredible stories from different parts of Afghanistan. Khatira Ahmedi, a producer at Zan TV, received numerous threats and has been boycotted by her neighbors and relatives. Her family still does not want her to work in media, but Ahmedi says, “I have ideas that need to be used and I see other women who have ideas that can be used as building blocks in this country. Why should I be kept behind four walls?”

Ahmedi says that one way for her country to emerge from the dark years of Taliban ideology is to “empower the women, give them a platform, let them join the nation-building process.” She says the country will never fully realize its own identity if all women in Afghanistan do not feel free. Ahmedi strives every day for women’s freedom by featuring them on the TV programs she produces, showing the nation the diversity of intelligent contributions women can make. “To empower women in the mainstream, in public, is the only way we can say no to discrimination.” She says discrimination is based on the assumption “that all women are inherently dumb. Now that is quite dumb,” she laughs.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]To empower women in the mainstream, in public, is the only way we can say no to discrimination.[/quote]

Many Afghan producers who are joining the media have been threatened. But they are taking risks because of the power of visibility all women gain from it. With each woman who joins the media, the movement earns a new milestone.

“It feels like we have taken a leap,” says Breshna, another producer with Zan TV, “something we had never achieved from any other work done in Afghanistan by foreign NGOs or government to improve the conditions of women in the country.” Breshna, who does not want to give her last name to avoid reprisal, used to work as a researcher at a foreign NGO that focused on education. While the work of educating girls and women has been crucial to helping Afghanistan, she says it has been too slow to bring any real change. “The real change comes when the idea of equality is not a struggle within a household, but a logic we can share on mass media, where the whole world is watching,” Breshna says. “And that is what I focus on in my programs: to make equality on public display and no [longer] a private debate.”

Luckily it is working, she says. She is seeing more women on TV and in the news; Afghan society’s mindset is shifting. The shift could be a result of the quickly spreading nature of media, she says. “These women who are on TV, seen as sports anchors and music show hosts, are directly entering people’s homes,” and that fact, she says, allows the people of Afghanistan to see these women as real humans: talented and bright and funny.

Back at the headquarters of Zan TV in Kabul, it is a busy time.

The meeting rooms at Zan TV buzz with women producers brainstorming the content of their program, centering their vision to provide a platform for Afghan women on their shows. During my midday visit, all the studios were busy producing recorded and live programs. In one of them, an interview with a former military commander was in progress, highlighting a woman who worked in the Afghan army for decades. She spoke about the harassment she faced during her job, producers explained to me, alongside the power and authority she enjoyed. It was a bold combination of strength and vulnerability on display. In another studio, a feminist went on air, without covering her head. “That is badass,” a producer told me.

I spoke to 20 members of ZAN TV and most of them expressed how they feel they are intervening the oppressive culture in the country by giving women more visibility in powerful and intelligent roles. The channel gives a platform to women in the air force, academia, music, and many others in roles unimaginable for much of the country. Many people in Afghanistan do not even know these women exist until the channel airs it on prime time, says presenter Shakila Rasooli. “The impact from our work is unquestionably empowering to women,” she says. “Our progressive vision surpasses the regressive vision of the dirty Taliban.”

In the year since the station’s launch, the country has seen major media attention, and women’s rights activists and academics claim women are now seen differently in Afghanistan. “This might sound so cheesy,” Soniya Azatyar, a freelance journalist in Kabul says, “but do you notice, how we might just be turning on the ‘lights, camera, action’?”

Azatyar explains that her work in the media will drastically help claim her equality, more so than any difference her daily struggle at home could have made. “Fighting in the house for me is much harder,” she says. “I can get grounded [restricted] and never be allowed to leave. But I can go out there and create content that not only my brothers but my entire neighborhood, my city, can watch. Slowly and indirectly if I can reach them, I can change their minds.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]My role in society, in this world, was to ‘clean the house,’ but I knew I was supposed to be more than that.[/quote]

Azatyar wants to change the minds of people, including her family, who she says have been brainwashed by social taboos. Azatyar says the misogynistic ideals men around her were bought up with have caused real paralysis in her life. She was not allowed to go to school and was not allowed to have a social life. She was only recently allowed to work because her family was struggling with money.

“I used to stay inside the house all day, all month, all year,” she says. “My role in society, in this world, was to ‘clean the house,’ but I knew I was supposed to be more than that.”

These women are at the frontline of a gender battle in Afghanistan. Through their efforts, they want to tackle the deeply integrated system of misogyny that runs through every class of Afghan culture. They come to work every day, earning extremely low wages — many of them without salaries at all — to interrupt the age-old mindsets that put women in the back seat. Through creating media content, they are rolling up their sleeves and marching in the arena. As Azatyar told me, “my ideas are my batons.”

Zohra Walid Rehmani, a feminist and academic, says the impact of more women in the media is visible in Afghan society. “We can see how it is OK to give jobs to women at restaurants; we see more doctors and nurses hired; we see fewer women with that ugly blue garb,” she says. “This incredible change comes from how progressive channels like Zan TV represent women. In fact, they are educating Afghanistan about women’s place in the country.”

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

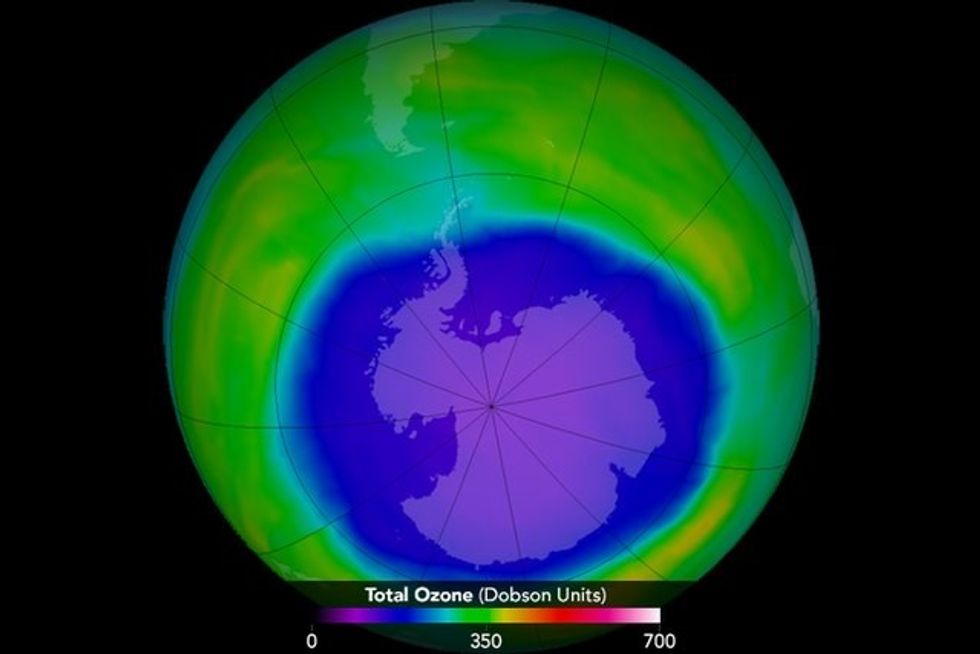

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva

In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva

Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva

Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva

Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

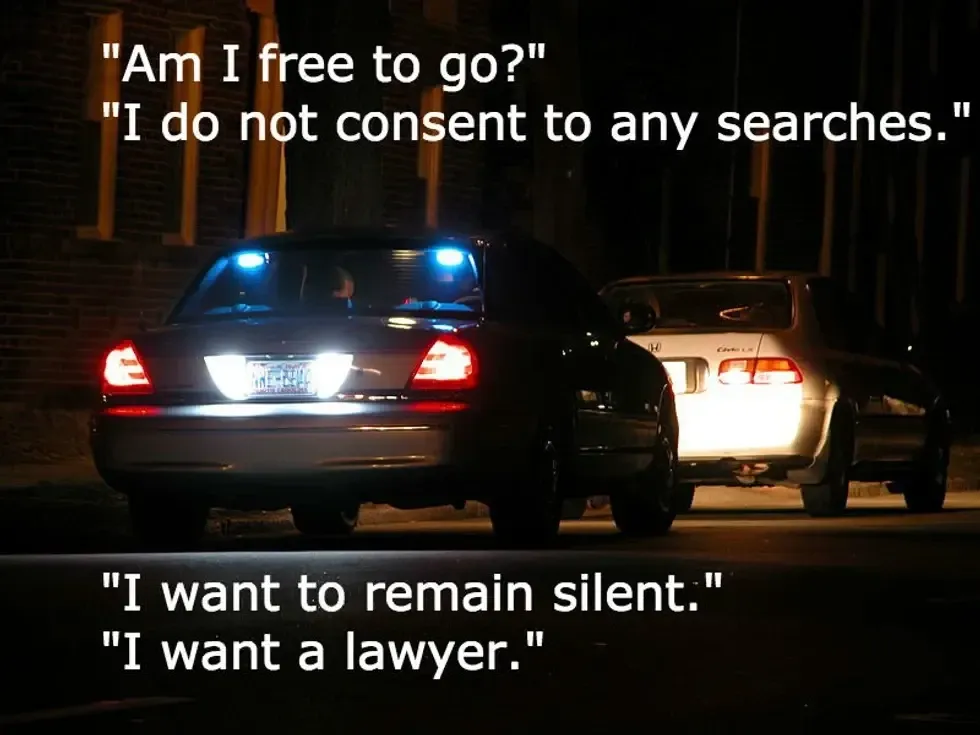

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.