It was like watching a coloring book come to life. For Art’s Birthday last January, Prague-based music-light duo ®udi22 played at the Papírna art space in Pilsen, Czech Republic.

Splashes of light filled the stage as the musicians used their handheld, pen-sized light sticks to pluck the laser strings. It was all in time with the minimal beats, as lasers shot out from the stage with one light-filled square dancing behind the musicians. They drew on the crisscrossing lasers, turning blue squares to green scribbles and red slogans, all while changing the sound pitch.

I turned around. The audience was mesmerized. Everyone was recording with their phones. If this were a purely audial musical performance, it would be a totally different story.

Are non-tacky, abstract light shows the future of electronic music? Put anything snap-worthy on a stage and the same old DJ-behind-a-laptop formula becomes extinct. There is an ever-increasing demand to be interesting, quirky or have a gimmick. But is light, especially when it isn’t VJ screen work, the answer?

“I think that emphasis on the visual is more significant in the case of instrumental compositions where it substitutes text,” said David Vrbik, who leads the Prague-based musical duo with musician Jan Burian, who hails from the Kyklos Galaktikos music project. While Vrbik played the light string treble, Burian played the light string bass.

“We do all the programming and make [the] toys ourselves,” he said.

Vrbik has been on the Czech music scene since 1998, though his “laser strings” instrument premiered in Brussels in 2008. It made its way to the spotlight in 2012 during the opening of the Olympic Games in London, where he performed at the Czech Olympic House.

Light design has become as important as sound. Take Squarepusher, who balance an audio-visual performance by adding a light show. Big Gigantic have toured in blue-lit pod booths and Skillrex has played in a sci-fi mothership. None of this is new, but it’s worth mentioning because ®udi22 are taking the basics to the next level. And there is an audience for this, both on a temporary and permanent level. Every October, the Luna Light Music and Arts Festival in Darlington, Maryland brings together light art and music with a pair of “light designers,” Brian McGregor and Randy MacCaffrie, who manage the installations.

Light, they say, is a material, like, wood, steel or mirrors. It isn’t just video projections, but the medium itself, which creates an atmosphere or a mood. LED lights, neon lamps or even fluorescent tubing are materials that hail back to the 1960s, harnessed in the minimal sculptures of Dan Flavin or even German light artist Otto Piene, who experimented with projections. While one could draw a parallel to color field paintings by Barnett Newman or Mark Rothko, Vrbik is influenced by more contemporary sound artists like Ryoji Ikeda and Carsten Nicolai.

“I have always been fascinated by sound visualization,” said Vrbik, who has been working for Prague’s contemporary music venue, the Archa Theatre, as well as a dance theatre for over 10 years.

“While composing music for dance performances, I would use a laser projector not only as a visual means but also as a source of synchronous sound. The laser string was another step.”

Vrbik works on an audio-visual, screen-based projection project called SPAM—a collaboration with Czech rapper Vladimir 518—which includes light installations. One SPAM video, “Interpretation of Black and White Structures of Zdeněk Sýkora,” pays homage to the titular Czech abstract painter, a well-known pioneer of computers art in the 1960s. Abstract patterns, inspired by the Kyklos Galaktikos music project’s work, are mixed with animations that call to mind the video game “Pong,” heightened by a spaced out soundtrack and a didactic-sounding Czech narrative.

®udi22 came about as a side project, which brings together improvisational sets alongside written tracks. The signals pass through Ableton Live and Max MSP software.

“We use a laser beam as the source of light,” said Vrbik.

“The audio chain begins with a light-stick that converts the changes of light intensity to an audio signal. We can program its oscillation frequency and use the Pangolin software or our own protocol for controlling the laser.”

To Vrbik, it’s about the balance of an interactive performance combined with screen-based projections.

“Interaction is not a priority here, it is about the propriety of the instrument (string) itself,” he said. “But I like both, the narrative of a projection, as well as the adventure of improvising on interactive instruments.”

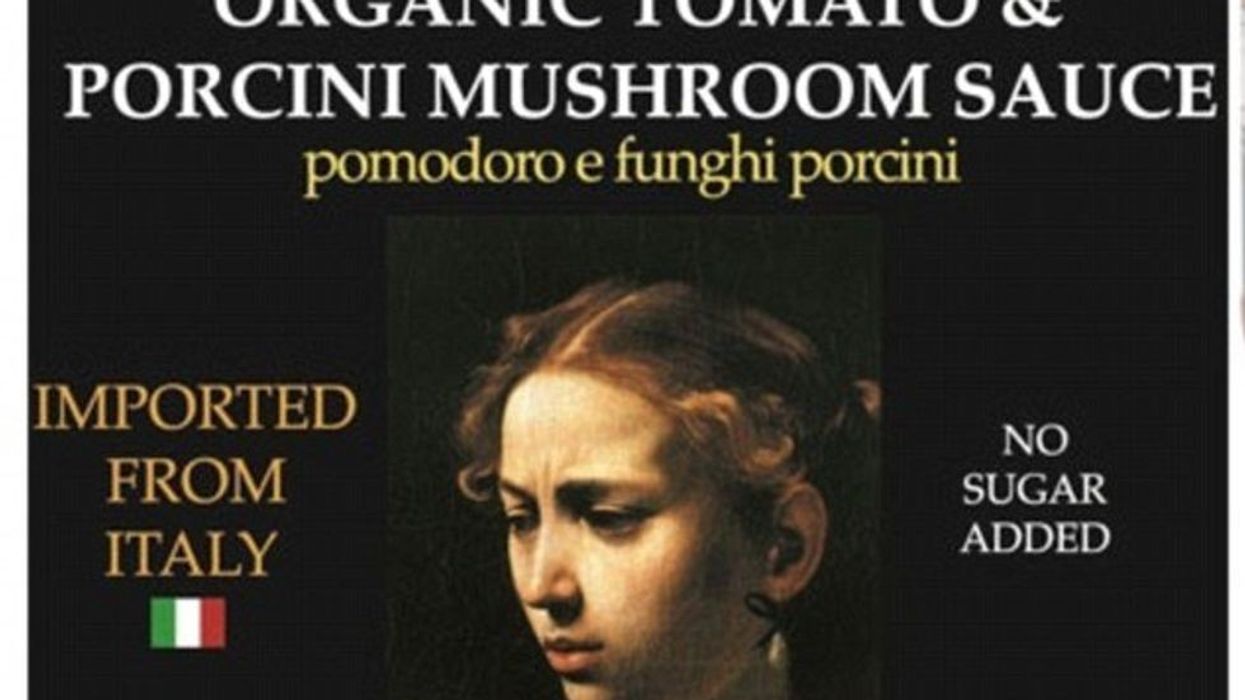

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)