Described as a "solidarity movement for gender equality," the HeForShe campaign is the United Nations' attempt to recruit men to the feminist cause. Launched last September with the star power of U.N. Women Goodwill Ambassador Emma Watson, the campaign became thinkpiece fodder and a Twitter trending topic for weeks after the Harry Potter actress took the stage to formally invite men to the women’s movement. As with anything attached to a feminist label, the campaign inspired plenty of contentious online discussion, from those who thought that it didn’t do enough for men to those who thought it did too much. These popular, contemporary debates embodied one of the major conflicts simmering within the feminist movement since the ‘60s and ‘70s: What role do men have in the women’s movement?

In recent years, this question has become especially poignant as domestic violence and rape scandals have wracked America’s most masculine institutions, from football to fraternities to the military. In the book Some Men: Feminist Allies and the Movement to End Violence Against Women, released earlier this year by Oxford University Press, researchers Michael Messner, Tal Peretz and Max Greenberg interview male feminist allies from three different eras of the women’s liberation movement, connecting the history of men’s activism to the current feminist moment. Messner, a sociology and gender studies professor at the University of Southern California, spoke to me about the book and the ways in which male feminist strategies have changed over the years to accommodate new understandings of both masculinity and the oppression of women.

The title of your book refers to the tension of men working in a leadership capacity for a movement that is supposed to be centered on women. How do the men you talk to in the book navigate that tension, and how do they negotiate their space within the feminist movement?

It’s really at the heart of what we wrote about in the book. Men, starting from that earliest movement cohort all the way through today, have had to figure out how to kind of strategize and negotiate within this field that’s created by women and for the most part has been run by women. The women that you see in the book are pretty much unanimously welcoming, and they see it’s important for men to do this work. But the flipside of that is that male privilege still operates within even those kinds of feminist fields, where you see men getting more credence for things that they say or getting put up on a pedestal and prematurely escalated into positions of power and authority.

Because male privilege is still with us, you can’t just make those things go away. The men who we interview, most of them are very well aware of those tensions and those contradictions. And they have learned, sometimes through experience, often through being mentored by older women and sometimes older men who’ve been doing this longer than they have, how to strategize to use that male privilege to get messages heard that people wouldn’t otherwise hear. But also make sure that [they] take opportunities when they arrive to credit women for having come up with the ideas. Young men who are hearing that message are invited to engage in a critical self-reflection about how they might not have been listening to women or might not have been hearing what women have to say.

A lot of these men were not attracted to feminism because they were angered by violence against women, but rather because they were antagonized by overt expressions of masculinity in the military or other domains structured by male dominance.

We tend to think, because feminism has illuminated this so much, that systems of male dominance put men over women, and they do. But systems of male dominance also include what I call inter-male dominance hierarchies, where men dominate other men, sometimes through class relations, sometimes through race relations, but also just men who are more conventionally masculine can dominate men who are not.

So a lot of the men who end up entering the movement to stop violence against women were themselves at some point victims of bullying, harassment, gay-bashing, violence, sexual assault, abuse when they were kids, or they saw their mothers and sisters getting beaten up by fathers. So they’ve been in environments where they have experienced violence. Often times, they were guys who were not conventionally masculine and were punished or marginalized because of that when they were young—because they were sensitized to these kinds of issues.

There are a few guys in the book who are more [conventionally masculine]. Ironically, those guys are probably most successful in the movement, in a conventional sense of success. They tend to be the ones who rise to positions of leadership. They get audiences. People listen to them. And that’s partly because they mobilize that more conventional masculine posture that they’ve developed. That’s another one of the contradictions of experience in the field, I think.

In recent months, we’ve heard a lot of conversations about football and football’s relationship to ‘conventional masculinity.’ Do you think football, and other aggressive, male-dominated sports, have a role in perpetuating masculine aggression? How do male feminists you spoke to perceive the sport?

The simple answer to the first half of your question is yeah, I think there is evidence that football and ice hockey and boxing do perpetuate a glorification of male violence. There is evidence that the boys and the men who are rewarded for being football players, and other aggressive athletes like that, are more likely to be involved in off-field violence, including violence against women and people who play other sports or don’t play sports.

Obviously, football is not going to go away right now, even though there is this concern about head injuries. I think the leagues and the NCAA are managing that as a public relations problem to a great extent. So the anti-violence activists on campuses who’ve worked with professionals as well as college football players are operating from the assumption that, for the time being, the sport is here to stay. The military is here to stay. And there are problems with violence that are particularly associated with those organizations. So, how do we get inside them and try to talk to men about consent and bystander behavior and domestic violence in ways that we hope might prevent some of it? That’s the strategy.

You see that with the fraternity issue as well—there is a very rigid gender binary built into the Greek system. Is there possibility for change within the fraternity system? Because we’re seeing a lot of backlash, and it seems like the fraternities at least are a softer target than the institution of football.

I think, though, there are differences within the fraternity or Greek system as well.

Part of it is being careful not to paint the whole system with the same broad brushstrokes. But at the same time, it’s clear that within the fraternity system there are major problems that have deep historical roots. There’s a powerful form of heterosexual male bonding in fraternities that makes the world more dangerous for women. That’s definitely one of the places that preventionists are targeting.

So part of that response has to be, beyond the important part of how do you deal with and how do you support survivors of sexual assault, which a lot of colleges have not done well at all, but in addition to that, how do you start going about creating a culture that confronts rape culture? And a culture that talks about consent, and bystander behavior, and people just being ethical towards each other on campuses?

You also talk about how these conversations work on an individual basis, that they sometimes fail to scrutinize the structural ways that rape culture is perpetuated. What kinds of efforts have you seen that target the more insidious ways rape culture is embedded within our society?

In terms of those really powerful masculinist institutions that I mentioned before—the military, organized sports, especially football: I don’t think the efforts that have been made so far have approached the structural problems that are partly at the root [of the] violence.

Some universities have, for instance, certain fraternities that are so egregious that they keep popping up. Universities have the power to control fraternities. I say that knowing that there’s a whole long history of universities having a very hard time controlling their fraternities.

It’s probably easier for them to do than to deal with the athletic department. Because the athletic departments, especially Division I universities, they’re like autonomous fiefdoms. They’re like the tail that wags the dog so often. It’s very, very hard for universities, I think, especially given the power of the alumni and the public, to really take control in a way that would make that kind of a difference. At the Division II and III levels, where you don’t have all that money involved, there can be a lot more elbow room for colleges to make changes. I’ve seen that in a limited sort of way in some of the colleges I’ve visited, that they’re trying to do sports right, and I think there is a way to do that.

How are men’s approaches to anti-domestic violence work, and other ‘feminist fields,’ changing?

Young men who are going into the work right now are going into, for the most part, pre-set organizations that often have pre-set curricula and pre-set ideas about who the target audiences are, and a lot of that has medicalized language, you know, talking about the ‘risk populations’ and ‘intervening’ to ‘prevent’ future acts of violence. There’s some ways in which that’s good. It facilitates the work, but I think it’s very limiting for people who have more of a political or social-change education to go into something that’s developing more and more into a professionalized social service.

On the other hand, though, a lot of the younger men who are going into the work are, as a group, a lot more diverse than the men of the 1980s and 1990s were. There’s a whole lot more men of color, there’s a lot more gay and queer-identified men going into this work. I think what that ends up doing is that it deepens the base of the work. That bureaucratization and the professionalization of the work has tended to kind of thin the politics. And the movement of men of color and queer men into this work provides the possibility of thickening the politics again. What those guys bring to the work is a life experience of having experienced or viewed violence in various ways—in the street, in their communities, in their schools, racial violence, violence perpetrated by cops against people in their community and families. They are more open to seeing men’s violence against women as connected to other forms of social injustice: poverty, racism, discrimination against immigrants. That’s what the younger guys are bringing to this now: a re-politicization of anti-violence work grounded in the experience of a more diverse group. That’s my most optimistic conclusion.

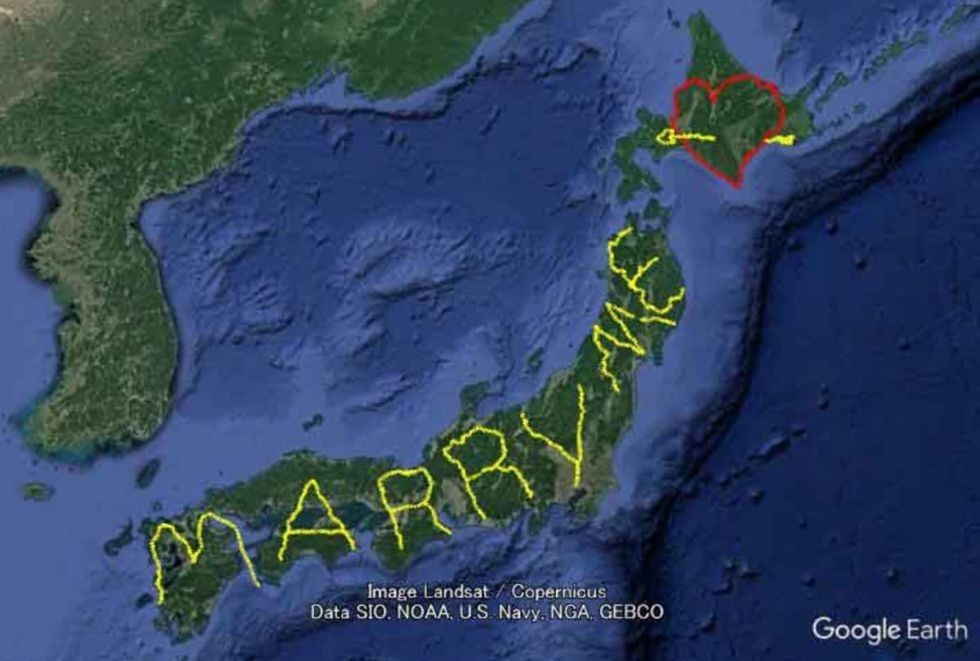

Yassan's GPS Drawing Project

Yassan's GPS Drawing Project

Elon Musk poses for a photo op.

Elon Musk poses for a photo op.

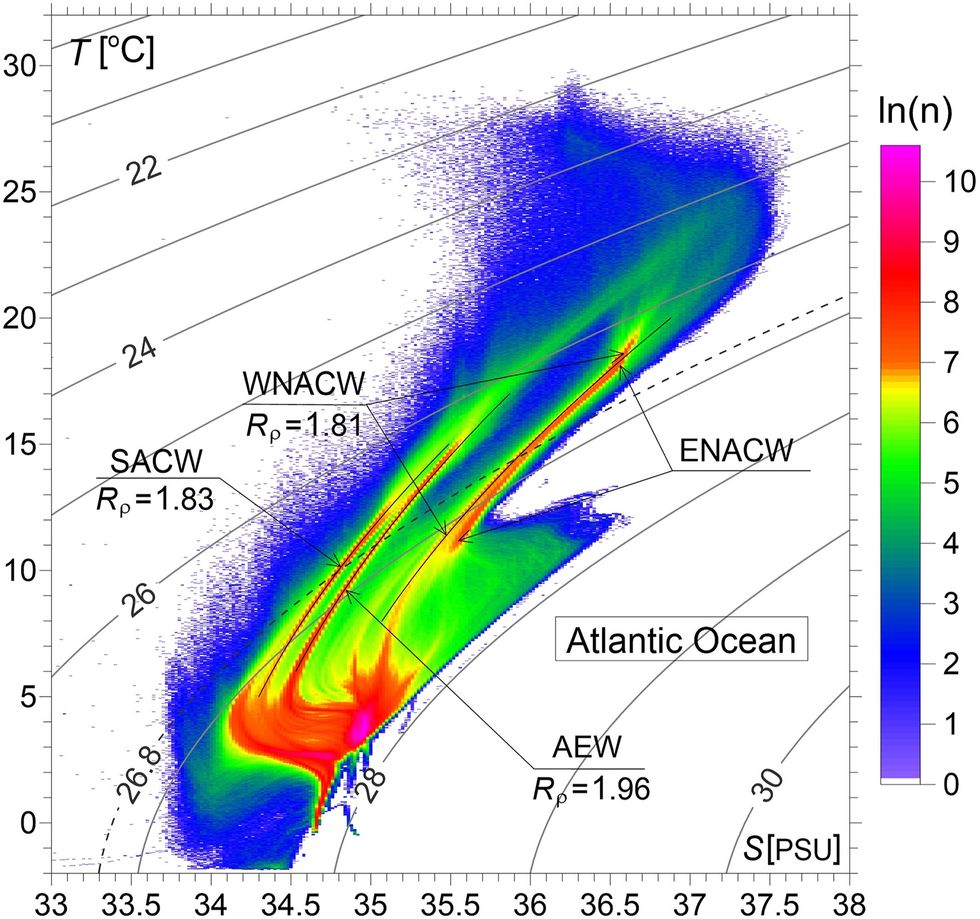

The Atlantic Ocean still holds secrets that scientists are hunting down.

The Atlantic Ocean still holds secrets that scientists are hunting down.  A detailed map was made using temperature and salinity profiles from the Argo data repository.

A detailed map was made using temperature and salinity profiles from the Argo data repository. Though you might not be able to tell one bit of water from another, scientists can and there are real consequences for the planet.

Though you might not be able to tell one bit of water from another, scientists can and there are real consequences for the planet.

The amazing dress began as an ambitious sketch.

The amazing dress began as an ambitious sketch. The final product, made entirely by hand, was a whimsical masterpiece

The final product, made entirely by hand, was a whimsical masterpiece