El Monte

“I was a little excited,” says Chamnian Thomas, standing in the 100-degree, late-July heat of El Monte, California, a 23-foot replica of the Statue of Liberty visible in the distance behind her. “I had never seen a prison in America before.”

Thomas, a 58-year-old woman from Thailand with shoulder-length black hair, was in the United States for more than two years before she found herself in a U.S. prison cell. But before doing more than a week behind bars for the U.S. government, Thomas was serving a different kind of sentence in a barbed-wire-enclosed sweatshop just a dozen miles east of Los Angeles. From the day she arrived in Southern California, lured by promises of a good wage and an escape from the poverty back home, Thomas had sat at a sewing machine for more than 14 hours a day, every day. She worked in the basement and slept upstairs on the floor of a room with seven other people. She was not allowed to leave. Nobody was.

“My friend invited me by saying, ‘You can make good money in America,’ ” Thomas recalls. She was faced with the certainty of lifelong poverty at home. Here were people promising to give her a fresh start and a middle-class lifestyle if she left everything behind. “They gave me these dreams,” she says. “They told me I would have a house to live in. And then they sent me to this place. ... I felt like I was in hell.”

Thomas was in hell until she heard the voice of Chancee Martorell, founder and executive director of Thai Community Development Center. “I heard Thai people yelling, ‘We come here to help, we come here to help.’ It was like I was going to heaven,” she tells me. That was August 2, 1995, when Thomas and 71 other Thai nationals were liberated in a pre-dawn raid conducted by state and federal agents. They had been tipped off that there was a sweatshop with slave-like conditions right in the L.A. suburbs. Until that point, Thomas had only left the house she lived and worked in once: to accompany her jailer on a trip to buy food, paid for with the $1.60 an hour she earned. Relatively speaking, she was lucky: Some of her fellow prisoners were subjected to forced labor for as many as seven years.

Thomas, smiling and chatty despite what she went through, remembers what it felt like to be lost and then found. “Finally I had hope in my life,” she tells me. “Someone was really here to help me.” That hope got her through nine days behind bars, where at least her meals were free. “The food was good,” she says, rubbing her stomach and laughing. “I had never had American food.” Today, Thomas lives in a four-bedroom home with her husband and child in the desert city of Palmdale. She cooks part-time at a local Thai restaurant. “If you want to come and visit, it’s on me,” says Thomas. If she was traumatized by her experience, she doesn’t let it affect her confidence. “My food is good. If you come over, you’ll know.”

I ask if she still sews. “Only for friends.”

The roots of Thai CDC

That 1995 raid served as a shocking notice to many Americans that the consumer goods they buy for so little come with an enormous human cost—not just abroad, but even when the label says, “Made in the USA.” It was also the first big test for Martorell and the Thai Community Development Center, which she founded the year before the raid. A Thai immigrant herself, Martorell came from Bangkok to Los Angeles when she was 4 years old. Her home life in the U.S., she says, was “stressful.” Her mother went from working for a train company in Thailand to cleaning rooms at motels. Her dad did a little bit of everything, from waiting tables at a country club to driving a taxi to driving an ice cream truck. Martorell was determined to make life a little easier for the families that arrived later.

In 1994, at age 26, Martorell founded the Thai CDC. Its purpose: to provide services to an underserved community of 100,000 Thai immigrants in Southern California, from legal aid to health care to affordable housing. (The group has developed 106 units for low-income seniors and families.) After attending grad school at UCLA, Martorell first went to work in government, thinking that was the road to social change. “Then I began to see how dirty politics is,” she tells me. “I decided I wouldn’t choose political expediency over my principles at any time in my life.”

The civil unrest that followed the Rodney King verdict in 1992, when four white cops were acquitted of all charges after participating in a videotaped beating of an unarmed black man, gave her a sense of urgency. If something wasn’t done to address the root cause of the riot, extreme poverty, then what happened in South L.A. would happen again in other neglected neighborhoods.

A year after founding Thai CDC, Martorell was invited to accompany state and federal agents on their raid of the El Monte sweatshop, where Thomas and others were being held, to provide aid and services to those about to be liberated. She was unsurprised to hear about the slave-like conditions that governed the lives of the workers. Martorell wanted to help, but she had one condition for the authorities: “You have to guarantee that immigration will not be involved since we’re involving foreign nationals without proper documentation.”

They met at a Yum Yum Donuts down the street at 4 a.m. An hour later she was informing six dozen people that they were free, at least for a time.

“Then, guess what? They called in immigration after I left,” she told me. The authorities had lied, according to Martorell, later claiming they locked up the rescued people for their own protection. Like the Thai family that enslaved them, the state kept the workers in cells against their will. “They were under another form of incarceration, at the hands of our federal government, and victimized twice over,” says Martorell.

Thai CDC and other immigrant rights advocacy groups immediately started organizing to demand the workers’ release, holding protests and press conferences outside the immigrant detention center in downtown L.A. The workers were released nine days later, on $500 signature bonds, after prosecutors designated them material witnesses to a crime.

Once the workers were freed, Thai CDC helped find them homes and jobs that paid a living wage. However, “as soon as the case was successfully prosecuted, the U.S. government, of course, thought, ‘Ok, now let’s send them home,’ ” says Martorell. The workers lucked out when a sympathetic INS agent took up their case and lobbied the U.S. attorney general for special visas typically reserved for those who snitch on international drug cartels, noting that the workers rightly feared retaliation if they were sent home.

Outraged that identified trafficking victims had to fight to stay, activists then fought for legislation that would grant future victims an automatic visa: the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Prevention Act of 2000. Now those the government considers “trafficked” can work legally while receiving medical care and housing. But the problem has become a labeling issue. Extreme cases warrant condemnation and the “trafficking” label—the El Monte case was even prosecuted as slavery—but other low-wage immigrants who are victimized by their employers, denied money they are owed and forced to work in dangerous conditions, are ignored or even treated as criminals. “I have experienced workers coming forward, reporting abuses, who are undocumented and then get summarily deported after getting picked up,” says Martorell, “and, of course, denied justice and their back wages.” Those who aren’t immediately kicked out of the country have the option of working behind bars, scrubbing floors for 13 cents an hour in an immigrant detention center.

“I see it as a manifestation of what the U.S. has done abroad,” Martorell says of those who come here hoping for a better life, only to suffer even more indignity. We “talk about democracy,” she says, “then end up installing puppet governments that support the U.S. at the expense of their own people.” Those people then come here; a few are officially recognized as victims, considered the rescued prey of traffickers. But many more are deemed exploited, perhaps, but their victimhood not worthy of asylum. All of them suffer.

A thin line between trafficking and exploitation

The Los Angeles Police Department has a dedicated Human Trafficking Unit, but it’s dedicated to investigating crimes “involving the sexual exploitation of human beings” and nothing else. “It’s salacious,” says Tia Koonse, a legal policy and research manager at the UCLA Labor Center, which studies and promotes policies aimed at improving the status of marginalized workers. “It appeals to people’s prurient interests,” she tells me, “to people who want to rescue ‘poor women,’ not actually have a worker revolution or do anything that protects and enforces the most basic labor protections.” Instead of effectively treating one form of forced labor as abhorrent while ignoring the others, Koonse suggests addressing “the things that predispose folks to being trafficked in the first place,” whether the destination is a brothel or a sweatshop, “which are the same characteristics [e.g., poverty, disadvantageous immigration status] that predispose people to being victims of [crimes like] wage theft.”

Wage theft exists on what Martorell calls the “continuum of exploitation.” Many of those with whom Thai CDC works are, in Martorell’s eyes, victims of trafficking: They were brought to the United States under false pretenses, paid less-than-legal wages, and threatened with violence if they complained. In the eyes of officials, however, many are just victims of wage theft, which can mean anything from unpaid overtime to a less-than-legal hourly rate. What that means is that, to this day, many who are victims of labor law violations are hesitant to come forward because the threat of deportation is quite real if the crimes perpetrated against the employee do not amount to trafficking in the eyes of the proper officials.

Laws that aim to prevent the exploitation of undocumented laborers have also been used against them. In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled in Hoffman Plastic Compounds, Inc. v. National Labor Relations Board that a company that fired an undocumented immigrant for taking part in a union organizing drive did not have to give him any back pay—money he had already earned—because he had lied about being a U.S. citizen to get the job. It would be a crime, the company argued, to knowingly pay such a person. Firing the employee for exercising his right to organize had already been ruled illegal by the National Labor Relations Board, but in the eyes of the court the worker in question had committed the original sin by crossing a border without the state’s consent. Since he was neither “trafficked” nor involved in something as salacious as sex work, the worker’s case became a legal precedent, not cause for reform.

When researchers with the National Employment Law Project surveyed more than 4,300 low-wage workers in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles in 2010, they found that foreign-born workers suffered minimum wage violations nearly twice as often as their U.S.-born counterparts. Women, especially those who were undocumented, were the most vulnerable—nearly half were paid less than required by law. Just under half of the individuals in this category were paid a sub-legal wage. According to Lucero Herrera, a researcher at the Labor Center, 42 percent of undocumented workers in LA are paid less than the $9-an-hour minimum, with the worst offenders being the hospitality and apparel industries. The theft adds up. The National Employment Law Project estimates that employers in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles shortchange their employees by a combined $3 billion every year.

Should they complain or try to organize in defense of their rights, employees here illegally risk serious repercussions, legal and otherwise. More than 40 percent of low-wage workers who tried to assert their rights reported experiencing some form of retaliation, according to the National Employment Law Project survey. Deportation is a real fear for undocumented workers, with employers regularly threatening to pick up the phone and call ICE when faced with worker discontent. Legalize these people, says Koonse, and you take away one of the easiest means of depressing wages. “If one of the biggest reasons why you’re not filing a wage claim is because you have a fear of retaliation based on your immigration status,” she tells me, “then if that status were to change ... it follows logically that more people would file wage claims.”

But there’s another reason the undocumented don’t file wage claims: In California, Koonse and other researchers at UCLA found that 83 percent of those who won their cases never collected a cent. All the process offered the victors was wasted time (wage claims can take over a year to be resolved) and an opportunity for the employer to insert their troublesome employee’s immigration status into the record. “They know what their employers know about their likelihood of collecting at the end after all that trouble,” says Koonse.

Kay Buck is the executive director of the Coalition to Abolish Slavery & Trafficking, founded in the wake of the El Monte case to assist trafficked workers with finding shelter and starting a new life. “People just simply don’t have safe ways to migrate, so they are going to be vulnerable,” she tells me. And to those desperate, vulnerable people, victimizers pitch a compelling service: navigating the byzantine U.S. immigration that wants to keep them out. Half of the organization’s clients initially come on legal visas, says Buck, traffickers having “learned how to abuse the system.”

Legal gray areas provide opportunities for exploitation. “They swoop in and say, ‘I’ve got a great opportunity for you. You can work in Los Angeles for a year and send money home. Your kids are going to be great,’ ” says Buck. When the worker comes to the United States and discovers those promises are false, that same entity may then threaten to harm the very kids it used as a selling point.

Buck sees how the immigration system enables and then compounds the suffering of victims, some deported for being victims of greed but not, in the eyes of the state, human traffickers. “We still have clients who are arrested today,” she says. “They’re treated like criminals,” given the boot instead of a visa based on an arbitrary divide between wage theft and trafficking. That’s why the coalition has endorsed legislation from state Senator Kevin de León, a Democrat from Los Angeles, that would give California officials more power to pursue employers who refuse to pay their employees.

L.A.’s global problem

Los Angeles is home to more than 3,000 registered garment factories, staffed largely by immigrants who have the liberty to go if they please but, like most low-wage workers in stagnant economies, are not really free to leave for good, whatever indignities they suffer. “It really has a lot to do with global capitalism,” says Martorell. “It’s a race to the bottom always for these corporations.”

Despite the conceit of its name, the “free” market seems to require a lot of slave labor. As many as 30 million people are enslaved around the globe today, mining minerals for our cell phones and sewing seams on our pants. And in the United States, where freedom is a dogmatic and oft-repeated trope of the national rhetoric, Thai CDC finds itself having to come to the aid of freed slaves everyday: Its slavery “response team,” part of the group’s Slavery Eradication and Rights Initiative (“SERI” means “freedom” in Thai) starts with immediate needs, providing victims food, shelter, clothing, and medical care, as well as legal counsel so that they can effectively fight to stay in the country and ultimately bring their families here with them. (A child or spouse back in the home country makes an easy target for a vengeful trafficker.)

After the El Monte case, Thai CDC continued to work on similar cases involving thousands of other Thai immigrants. One recent case backed hundreds of farmworkers brought to Hawaii by the labor contractor Global Horizons as part of the U.S. agricultural guest worker program—what Martorell calls “a legalized form of slavery.” The migrants were told they could work for three years at minimum wage, providing enough time to repay the considerable debts they incurred paying for the privilege to work in the first place. Some were housed in an abandoned schoolhouse, 18 to a room, and threatened with both guns and deportation if they complained. Phone calls were monitored and passports confiscated. Asked to intervene because of its experience in such cases, Thai CDC fought to hold the employer liable for their labor violations. In 2014, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission awarded around 500 former employees $2.4 million for their ordeal.

Despite the involuntary nature of their employment, these workers were not considered “trafficked.” Which raises the question: How many more people are not enslaved, per se, but have no real choice?

“Poverty is just another form of slavery,” Martorell argues. It’s not chattel slavery, to be sure, with whips and chains, but a more subtle form of coerced labor that some accept as the natural state of things, the alternative to selling one’s body as a laborer being abject poverty.

That’s one reason why Thai CDC did something one might not expect from a group focused on immigrant rights. In 2010, the organization opened a farmers’ market in the heart of East Hollywood to provide fruits and vegetables in what was once a food desert. Located on top of a subway station, the market caters not to the well-to-do residents of Hollywood proper but to low-income immigrants from Asia and the Americas. The market has thrived, serving about 15,000 customers a year. When I stopped by last summer, I saw hundreds of people, mostly young mothers with their small children, waiting in a long line to trade in a $20 WIC check (Women, Infants, and Children is the federal food subsidy program for poor women and their children) for twice that value in vouchers for fresh produce. The program, administered by Thai CDC, is called “Market Match.” The scene was illustrative of the task before community activists like Martorell. The services her organization provides are clearly meeting the needs of many. But more than a hundred people also went home without any fruits and vegetables after waiting for up two hours because Thai CDC ran out of money to give away that day.

More funding would be helpful, but Martorell is more interested in empowerment than charity. She wants to bring immigrants together so they can demand more money for themselves. “If you could just stand together,” she tells them, “the more power you’ll have.

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva

An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

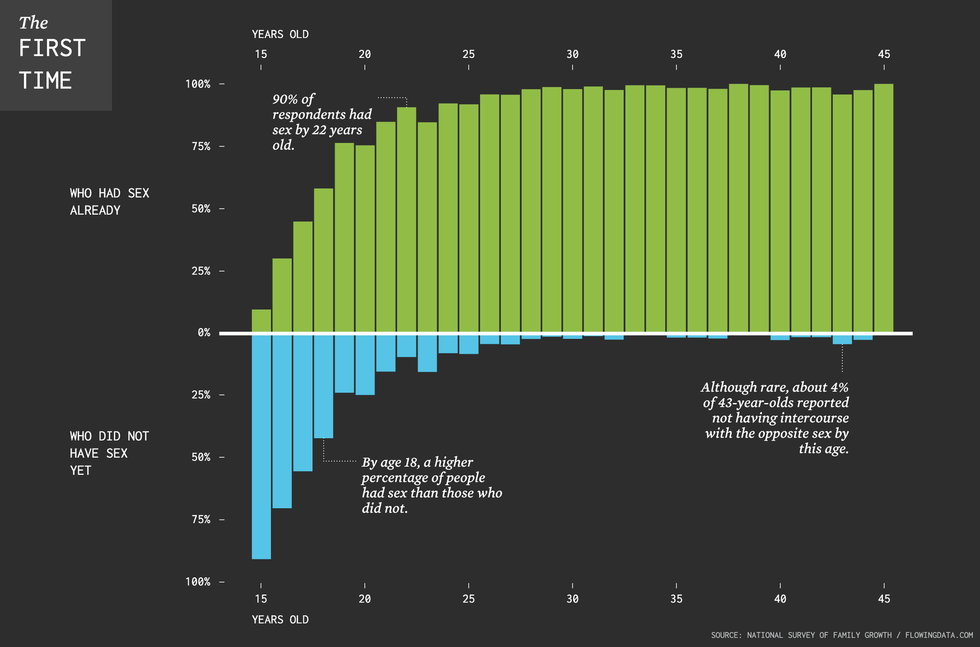

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex.

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex. A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/

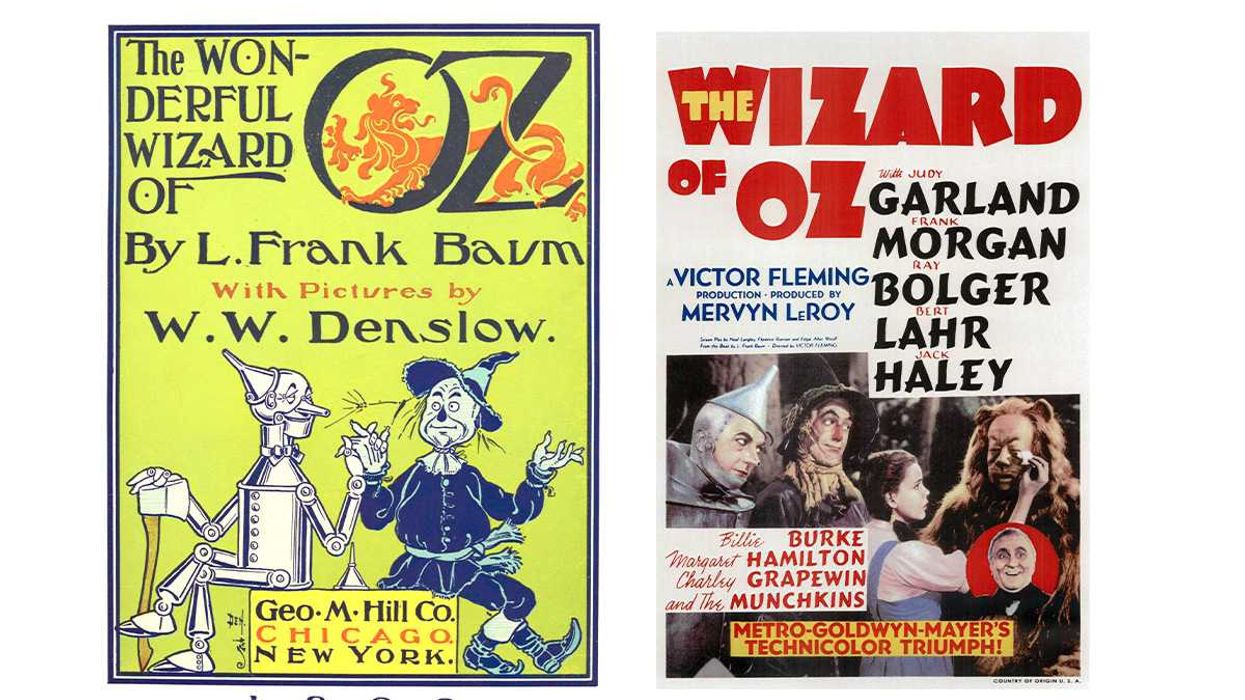

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/  (LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

(LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via