“I go to the flea market because it is full of small, hidden histories,” artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres said in 1995, during an interview for BOMB Magazine with fellow artist Ross Bleckner. Revisiting Gonzalez-Torres’ work now, the statement is poignant. In its own way, his work is also filled with small, hidden histories.

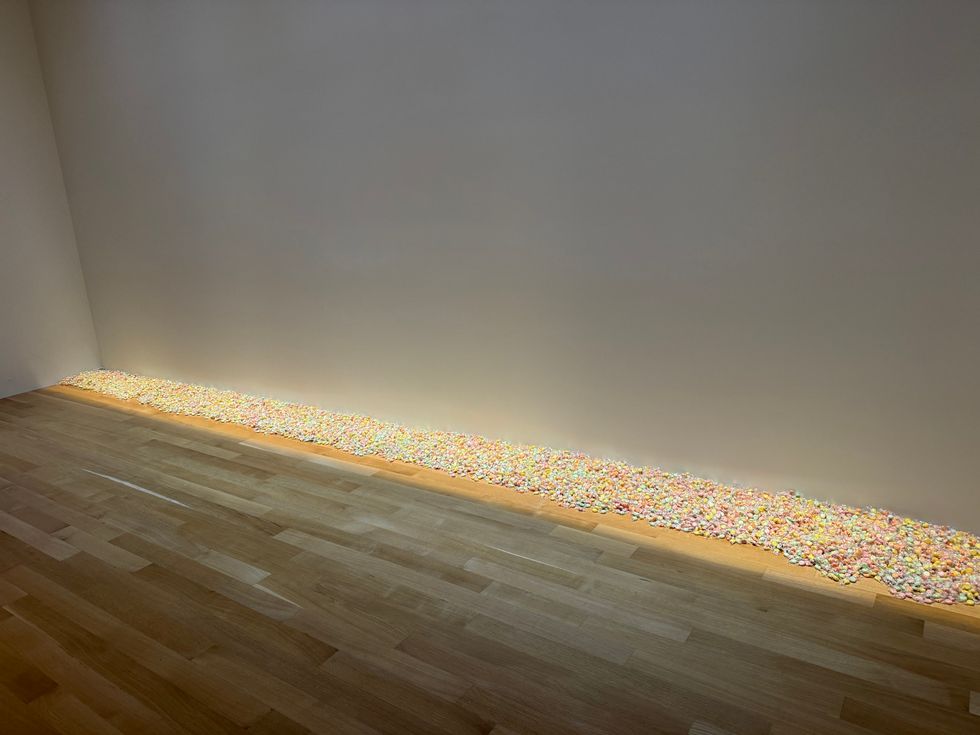

The Cuban-American artist–who was openly gay in the 1980s and 1990s, when it would have been more rare–became known in his lifetime for his conceptual art that lived across mediums of sculpture, installation, photography, painting, and more. Among his most noteworthy series are his “Candy Works,” whose installation in any given space featured an “endless supply” of sweets, from fortune cookies to chocolates to hard candies. Audiences were–and are still now–invited to have a piece and eat it. The work will ebb and flow as it is filled and refilled. It’s in these works that hidden histories–or maybe not so hidden–have most recently been discussed.

Gonzalez-Torres created several candy works in memory of his love Ross Laycock, who passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1991. They too feature never-ending supplies of candies in colored wrappers, to be taken and discarded as in his other work, though this time the echo of loss is so much louder. It can mirror the way AIDS ravaged Laycock’s body, scholars believe, while also living forever in his honor. Gonzalez-Torres and Laycock were together for eight years, the artist said in BOMB. “I never stopped loving Ross. Just because he’s dead doesn’t mean I stopped loving him,” he went on. He defined the years of 1990-1991 as some of the most difficult in his life, and often said his work was made “for an audience of one,” meaning Laycock. Gonzalez-Torres himself passed away from complications due to AIDS in 1996.

One of these works, “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” below, faced controversy recently for the way it was displayed. An exhibition of Gonzalez-Torres’ work, “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return,” is appearing now at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery and the Archives of American Art. The art scholar Ignacio Darnaude chastised the museum in OUT Magazine for eliminating mentions of AIDS, Laycock, and queerness from the work's wall text:

“The irony is that, by not explaining what Portrait of Ross in L.A. truly means, the National Portrait Gallery has turned his work into an esoteric cypher, depriving visitors from experiencing Felix's revolutionary work in portraiture. Instead of inducing emotion and tears, I witnessed people blissfully taking pictures of pretty candy — empty calories on the floor robbed of their stirring spirit,” Darnaude wrote. Darnaude also cites that curator Jonathan D. Katz spoke of the work in a 2010 National Portrait Gallery show, directly relating Gonzalez-Torres’ work to AIDS, to understanding how it destroyed a person, and how so many participated in culture and policy that let people die.

The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation has since spoken out against the article, instead saying that the curators “have done an extraordinary amount of research and have not only made a point of incorporating significant queer content throughout this exhibition (including direct references to Gonzalez-Torres’s queer identity, his partner Ross Laycock, and both of their deaths from complications from AIDS), but have provided a generous forum for a vast and diverse audience to engage with this content, other political content, and Gonzalez-Torres’s work.” Some refute the foundation’s claims, others agree.

Gonzalez-Torres’s work actively negotiated public space and private life–at the time “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.)” was created, as Darnaude cites Katz, the artist had to find other ways to talk about AIDS in his work because of increased censorship and homophobia in the government. Gonzalez-Torres found a way to bring his voice into systems that otherwise might have sought to oppress it. His work remains perpetually connected to AIDS, to the travesty it wrought on the LGBTQ+ community and the ways the community fought back. It’s a powerful moment to think back on now as the LGBTQ+ community once again faces challenges from the government, particularly in terms of healthcare.

For Gonzalez-Torres, his voice always mattered. “I think that art gives us a voice. Whatever it is, whatever we want to make out of this thing called art,” he said in 1994. “There are different institutions; in the same way that there are a lot of different artistic projects that we can use for our won ends. That's how I see art, as a possibility to have a voice. It's something vital.”

The Zoo is also a great place for a date.

Photo by

The Zoo is also a great place for a date.

Photo by

Photo credit: National Basketball Association

Photo credit: National Basketball Association

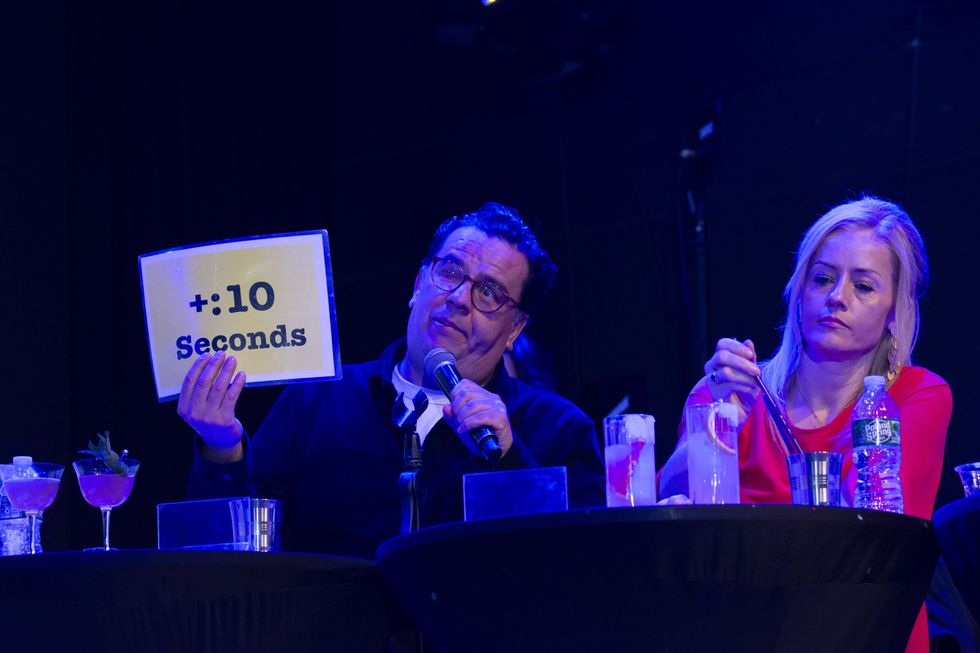

Competitors Sam Smagala, of the bar Joyface, and Miranda Midler, Head Bartender of Dear Irving's Broadway location, shake it off before Round 1 begins. Elyssa Goodman

Competitors Sam Smagala, of the bar Joyface, and Miranda Midler, Head Bartender of Dear Irving's Broadway location, shake it off before Round 1 begins. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Hope Rice of The Crane Club finishes up the final cocktail of her round, an Old Cuban, with a pour of G.H.Mumm Champagne. The Old Cuban is a drink created by legendary bartender Audrey Saunders. Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Hope Rice of The Crane Club finishes up the final cocktail of her round, an Old Cuban, with a pour of G.H.Mumm Champagne. The Old Cuban is a drink created by legendary bartender Audrey Saunders. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Ileana Hernandez just before her round begins. Ileana works at Greenwich Village restaurant Llama San.Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Ileana Hernandez just before her round begins. Ileana works at Greenwich Village restaurant Llama San.Elyssa Goodman Full of friends and industry professionals, the audience cheers for the annual New York Regional Speed Rack competition. Elyssa Goodman

Full of friends and industry professionals, the audience cheers for the annual New York Regional Speed Rack competition. Elyssa Goodman Competitor Rachel Prucha, of Mister Paradise and Hawksmoor, ready to take on her round.Elyssa Goodman

Competitor Rachel Prucha, of Mister Paradise and Hawksmoor, ready to take on her round.Elyssa Goodman Bartender Lana Epstein, of The Portrait Bar, wins Speed Rack's New York Regional competition. Friends and fellow competitors raise her up and offer bubbly to celebrate. Elyssa Goodman

Bartender Lana Epstein, of The Portrait Bar, wins Speed Rack's New York Regional competition. Friends and fellow competitors raise her up and offer bubbly to celebrate. Elyssa Goodman

Lounge Painting II, 1983, Gila Bend© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery

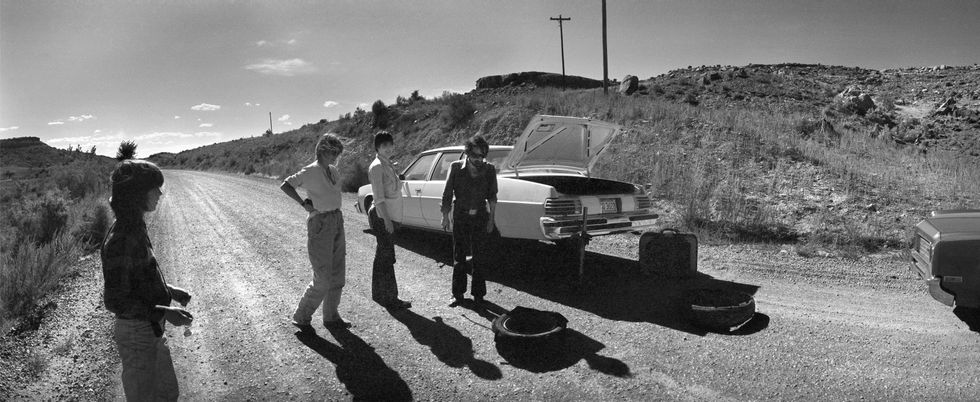

Lounge Painting II, 1983, Gila Bend© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery When Martin Scorsese had a flat tire II, 1977© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery

When Martin Scorsese had a flat tire II, 1977© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery John Lurie, 1986, Montreal© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery

John Lurie, 1986, Montreal© Wim Wenders/ Wenders Images and Howard Greenberg Gallery

Galentine's Day 2025Elyssa Goodman

Galentine's Day 2025Elyssa Goodman Galentine's goodiesElyssa Goodman

Galentine's goodiesElyssa Goodman

Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack