Every August for the past 16 years, Cambridge Brewing Company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has ordered more than 4,000 pounds of sugar pumpkins from local farms. With the help of friends and family—and a handful of volunteers—employees chop, gut, and shred every one of those iconic New England gourds to ready them for brewing in their 14 different limited-edition pumpkin beers, most notably the coveted Great Pumpkin Ale.

Brewmaster Will Meyers refuses to bend to industry norms and use extracts or purées. Today, it’s one of the only three breweries of its size in the United States that uses freshly harvested pumpkins, a tradition that means even more this year as record droughts stress local farms’ already lean margins.

New England is currently suffering its worst dry spell in 14 years. In August, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker was compelled to urge Massachusetts citizens to spend their grocery money on local produce in an effort to help keep farms afloat. “The farms are really suffering,” Meyers says in an interview with GOOD. In these conditions, a standing order for a few thousand pounds of a single crop can make or break a harvest, and Meyers doesn’t downplay the impact a brewery of CBC’s size can have on the surrounding agricultural community. “Lazy Acres did say a lot of their crops aren’t doing well, so they appreciated the sale of the pumpkins just to get some cash,” he says.

The plight of American farmers in times of drought is exacerbated by the fact that the Federal Emergency Management Agency does not recognize drought as a disaster, meaning the usual federal relief associated with weather-related losses isn’t available. In 2011, drought throughout the Southern Plains states resulted in more than $10 billion in financial losses for the agriculture industry, and California farms are bracing for a third year of drought conditions. In May, the USDA responded to country-wide drought and severe weather conditions with a series of what it calls Climate Hubs, designed to help farmers make “climate-informed decisions” in the face of difficult conditions, according to its website.

A 27-year pioneer of sustainable brewing practices, Cambridge Brewing Company is devoted to conscientious production in a way most breweries can’t touch, instilling graywater treatment practices, composting, and using energy-efficient equipment, but it’s its ongoing partnerships with the local farming community that mean the most this year.“It’s about relationships,” Meyers says about CBC’s loyalty to farms such as Lazy Acres and Valley Malt, where most of the grain is sourced for brewing, though he admits it can be a challenge to rely on nature instead of a production schedule. “Sometimes it’s hard. We’re under deadline at the brewery to get [the beer] out or we won’t be able to compete. We’ll never be first to market with this beer because industrial brewers are starting with purées in April, and we’re waiting for the pumpkins to ripen as late as August.”

In the case of Great Pumpkin, CBC’s flagship pumpkin beer, patience and collaboration pay off. The ale has a nearly perfect rating of 96 points from the experts at top beer rating magazine BeerAdvocate, and it’s among the company’s most sought-after brews. “It’s really laborious,” Meyers says, “so I’m glad when people can appreciate that.” Still, he’s aware of the industry-wide progress to be made. “The renaissance is still nascent. It’s one thing to think that if you have your CSA and eat local cheese and drink local beer that you can relax and take it for granted. That concerns me. Only small parts of the country are able to embrace local industry and local agriculture. There’s a lot more work to be done to make sure that breweries everywhere are able to work with and incorporate as much local agriculture as possible.”

In many ways, this comes down to consumer education. As big agriculture continues to grow, a small farm’s tenuous existence can be brought to its knees in the face of one dry season, and it’s no longer enough to support your local brewery. Meyers argues that consumers have to be sure the beermakers they’re purchasing from are using are local ingredients, too. “As with most things, the average consumer doesn’t ask questions about how they spend their money and how important it is to keep their dollars in the local food chain,” he says, though he remains hopeful about the future of the industry. “Younger brewers and consumers are a little more suspicious of industrialization and corporatization. New breweries are really conscious of opportunities to work with local farmers and producers. It’s not just another opportunity to express themselves creatively and differentiate—it’s an obligation.”

This year, that sense of obligation came through not just for the farms, but for the beer. “We were hearing the pumpkin crop was going to be bad this year because of the drought, but instead they’re really sweet, really in great shape,” Meyers says. The combined heat and lack of rain encouraged early ripening as well, meaning Meyers and his team could brew earlier than anticipated and keep up with the rest of the market. That led to Great Pumpkin being released a full two weeks ahead of schedule, and CBC’s lineup of five brewer-specific, limited-edition pumpkin beers will be showcased at its 9th annual Great Pumpkin Festival on October 29.

According to the USDA’s website, “a changing climate is expected to continue impacting agriculture for the foreseeable future.” As American farmers attempt to adapt to what they can’t control, supportive community members like Will Meyers and Cambridge Brewing Company are a potential lifeline in a time of crisis. For consumers across the nation, CBC’s Great Pumpkin Ale means fall; this year, for a few Northeastern farms, it meant survival.

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen

Freddie Mercury GIF by Queen File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

File:Statue of Freddie Mercury in Montreux 2005-07-15.jpg - Wikipedia

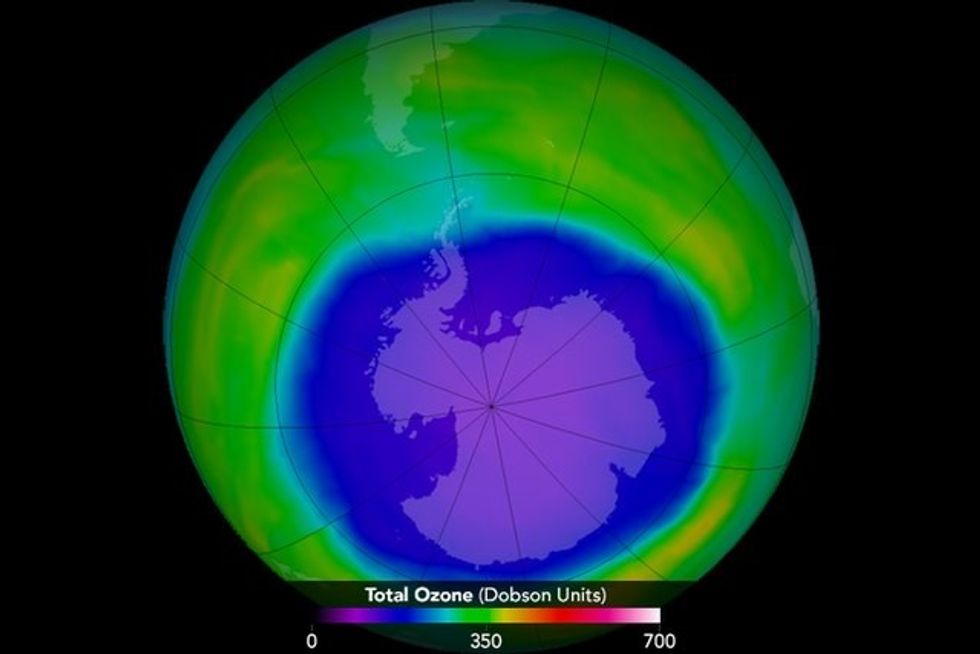

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The hole in the ozone layer in 2015.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva

In the 1980s, CFCs found in products like aerosol spray cans were found to cause harm to our ozone layer.Photo credit: Canva Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Group photo taken at the 30th Anniversary of the Montreal Protocol. From left to right: Paul Newman (NASA), Susan Solomon (MIT), Michael Kurylo (NASA), Richard Stolarski (John Hopkins University), Sophie Godin (CNRS/LATMOS), Guy Brasseur (MPI-M and NCAR), and Irina Petropavlovskikh (NOAA)Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva

Getting older means you're more comfortable being you.Photo credit: Canva Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva

Older folks offer plenty to young professionals.Photo credit: Canva Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva

Eff it, be happy.Photo credit: Canva Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva

Got migraines? You might age out of them.Photo credit: Canva Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Old age doesn't mean intimacy dies.Photo credit: Canva

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

University President Eric Berton hopes to encourage additional climate research.Photo credit: LinkedIn

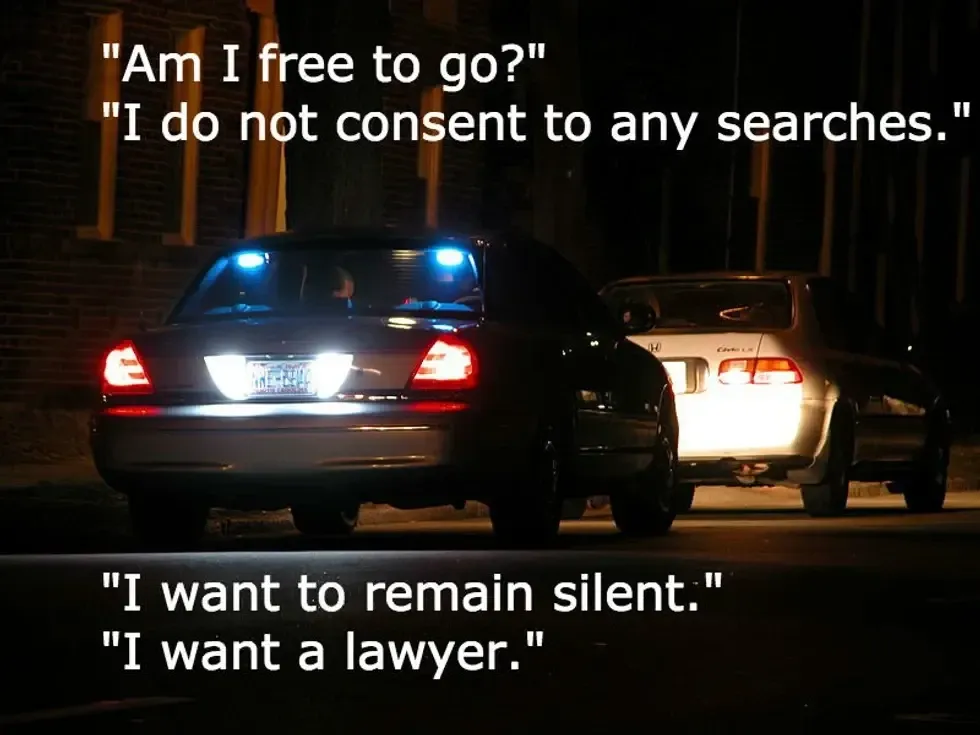

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.

Image by Ildar Sajdejev via GNU Free License | Know your rights.