“Women can be good photographers much in the same way that they can become good doctors, good cooks or whatever they choose to be good at,” Lisa Larsen said in the mid-1950s. By that point she had become one of LIFE Magazine’s most successful photojournalists, having already won Magazine Photographer of the Year in 1953. In that time, she became known for her interest in the truth of humanity. “I dislike anything superficial and I especially dislike superficial relationships,” she said in 1954.

Lisa Larsen, née Rothschild, arrived in the U.S. as a Jewish emigre from her native Germany–her family left after Kristallnacht. She was just a teenager at the time, but knew the career path that was right for her. By then, a group of German Jewish photographers had elevated photojournalism as an artform in the U.S. and formed the influential photography agency Black Star, one of Magnum’s greatest competitors. Larsen joined them as a file clerk. She then began her career as a freelance photographer for magazines like The New York Times Magazine, Vogue, Seventeen, Glamour, and more, but she worked at LIFE for a decade beginning in 1949.

At first, as a woman, she was relegated to fashion and entertainment photography–she took photos of Marlon Brando and Grace Kelly, for example, though even those somehow situate megawatt stars of the time as mere mortals, a way audiences hardly got to see them then and, arguably, still now.

Over time, Larsen was able to expand her practice and become an intrepid, adventurous world traveler. She became, for example, “the first American photographer to enter Outer Mongolia after a government-enforced 10-year ban,” as LIFE wrote. She also traversed the Himalayas; photographed world leaders at the first Bandung Conference in Indonesia, which sought to solidify African-Asian relations’ and Eastern Europe during the Cold War in 1955, among many others. She was additionally sent to photograph high-ranking political figures from Dwight D. Eisenhower on his campaign for president and First Lady Bess Truman, wife of Harry S. Truman; to Nikita Khrushchev and the 1953 wedding of Senator John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, not to mention Queen Elizabeth II’s first tour as a royal.

Larsen was known to be both charming and hardworking, and knew how to get a great photo. In her time, she dazzled many a world leader. “Appreciative Khrushchev gave Larsen a bouquet of peonies,” scholar Patryk Babiracki wrote in Apparatus Journal. “Ho Chi Minh spotted Larsen…and confessed: ‘If I were a young man, I'd be in love with you,’” Babiracki continued. Truman Vice President Alben Barkley called her “Mona Lisa.” According to the International Center of Photography, “she photographed Iran’s Premier Mohammed Mossadegh from his New York hospital bed during the 1951 Iranian oil dispute with Great Britain,” which “led to a personal invitation from Mossadegh to visit Iran for a two-week vacation.”

Opening doors with her personality and “glamour girl” good looks, she was able to take pictures many couldn’t, especially men–and this is at a time when not nearly as many women were employed as today, let alone as photojournalists. But first and foremost, she was a good photographer. In all of her work, she looked for the truth, even within a medium as subjective as photography. Indeed, this is evident in her photographs even looking at them some 70 years after the fact; it feels like she’s trying to show us something about the world that hasn’t just gone unseen, but unconsidered. Larsen was not convinced, for example, of the cut-and-dry stories America sought to tell of its supremacy during the Cold War, as Babiracki wrote. Rather, he writes, “her visual work reveals a woman who appreciated the ambiguity of photography and sought to shape the meaning of her work in a way that challenged the prevailing Cold War epistemologies of midcentury America, often espoused by Life and the Time/Life empire itself.” Changes in hairstyles and clothing aside, Larsen’s work still feels fresh even now.

Tragically, Larsen’s life was cut short by breast cancer in 1959, when she was just 36 years old. Even as she knew there’d be no cure for her illness, however, she continued photographing; Babiracki believes this created even more of a sense of urgency in her work. It had to be captured, it had to be now, and it had to be real.

Arguably, though, these feelings live throughout all of Larsen’s photography. In May 1950, she wrote an article for Esquire magazine titled “The Woman Behind the Camera” which also featured her images. Though written in the context of how she photographed women, her thoughts apply across all of her work: “I do my best to see the truth,” she wrote, “for I’ve discovered that the truth, which may sometimes seem ugly, is always, at the same time, breathtakingly beautiful.”

Prepping the pieCanva

Prepping the pieCanva Pepperoni sliceCanva

Pepperoni sliceCanva Pizza partyCanva

Pizza partyCanva

Cozy pizzaCanva

Cozy pizzaCanva

Making the pie from scratchCanva

Making the pie from scratchCanva Image Source: Reddit I

Image Source: Reddit I  Image Source: Reddit I

Image Source: Reddit I

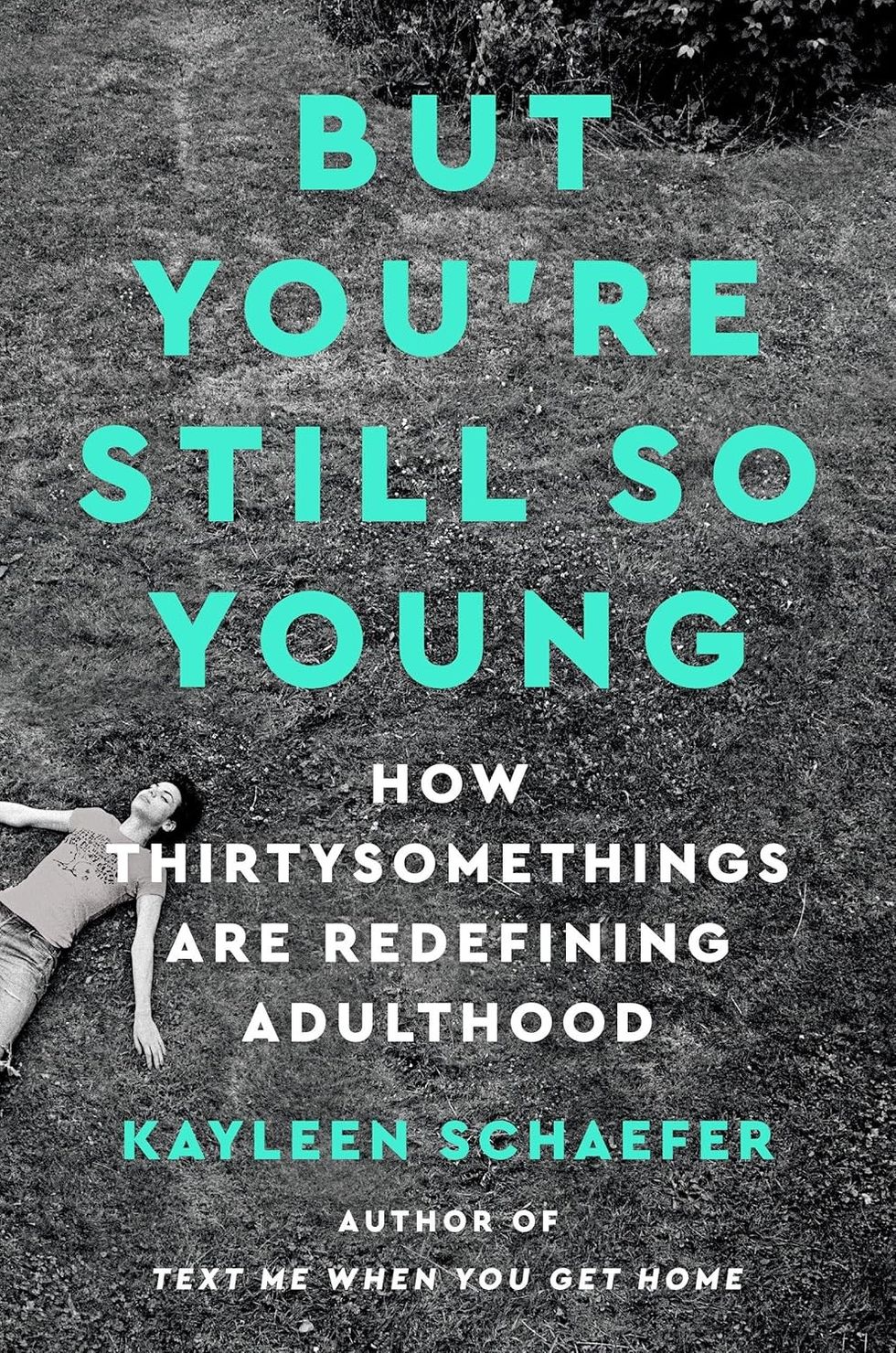

Many people say their 30s are when life starts to click.Representative photo by Canva

Many people say their 30s are when life starts to click.Representative photo by Canva Stress and satisfaction often go hand in hand in your 30s.Representative photo via Canva

Stress and satisfaction often go hand in hand in your 30s.Representative photo via Canva

Taking orders.Canva

Taking orders.Canva Happy dinersCanva

Happy dinersCanva Not everyone loves tipping culture.Canva

Not everyone loves tipping culture.Canva Being a server is demanding work.Canva

Being a server is demanding work.Canva Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |  Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |  Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |