Scotty Coats has devoted most of his life, in one way or another, to the eternal music medium of LPs: circular pieces of sound-producing plastic that have survived over a century, through the CD boom and digital revolution, into a strange and uncertain future. But the more he learned about the environmental impact of producing these works of art, the more he started to question his role in it. That uncertainty resulted in Good Neighbor, a radical business venture that challenges us to rethink the world of "vinyl"—and even the very use of that term.

The California native—who grew up in Mission Viejo and has resided in Long Beach for nearly two decades—has worked in just about every facet of the music industry, from a stint as vinyl buyer at Tower Records to serving director-level and managerial roles at revered labels like Stones Throw, Innovative Leisure, and Virgin Music Group. Given that he’s bounced around like a pinball, it wasn’t unusual that he’d consider another career pivot in his mid-40s. But he definitely wasn’t expecting the phone call that changed his life.

"Probably two and a half years ago, a friend of mine, Tim Anderson, who was a staff producer and A&R [executive] over at Harvest and Capitol, was like, 'Hey, I want to scrape the oceans of plastic and make records,'" Coats tells GOOD. "I was like, 'That sounds amazing. Count me in!’"

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

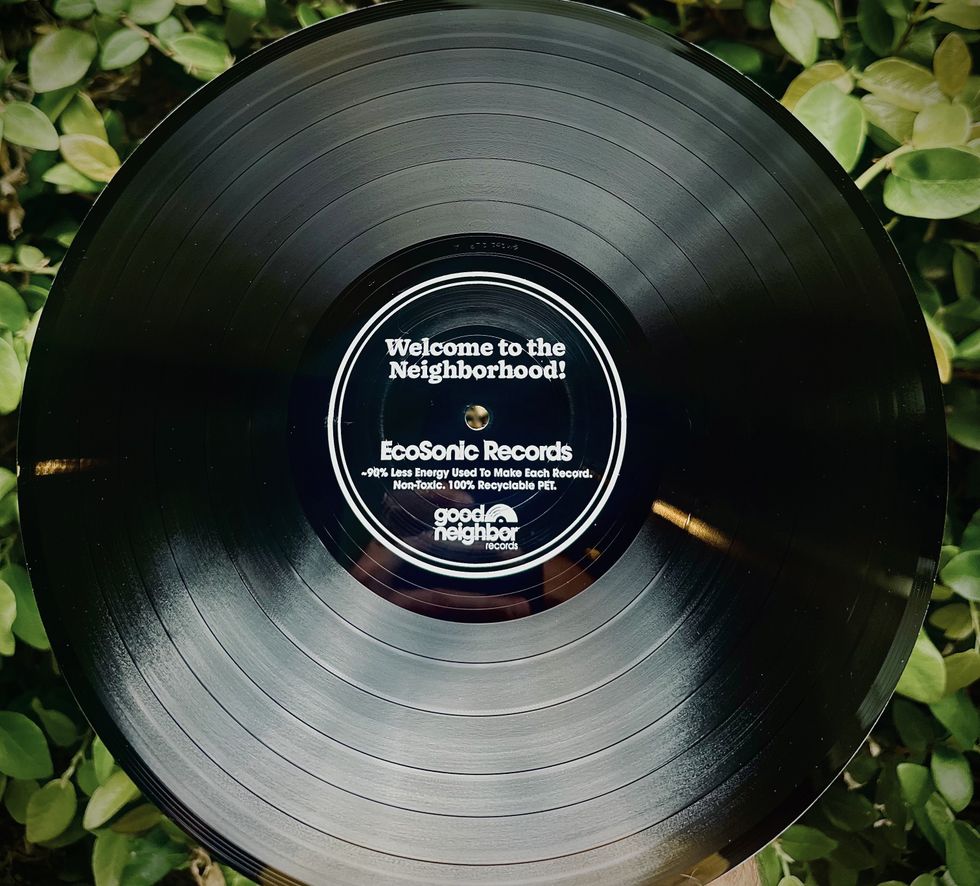

After building a team, making contacts in the industry, and doing tons of quality control, the duo officially launched Good Neighbor, an eco-friendly record-manufacturing company aiming for a "cleaner supply chain and sustainable future." Their patented product presents an alternative to the traditional vinyl that record-heads know and love: a "non-toxic and fully recyclable material," created using an injection molding process rather than a hydraulic press.

According to their website, vinyl production results in roughly 125 million kilograms of CO2 pumped into the air, with "44 million kilograms of highly toxic PVC" used to create vinyl. Coats says the company’s process takes an elevated path, resulting in a product created with more efficiency, less guilt, and, crucially, minimal to zero reduction in sound quality. (Note: Good Neighbor sent me some sample LPs to test out. I’m an obsessive record collector who hosts a YouTube series about this very topic, though I’m far from an audiophile or recording engineer. That said, these records sounded great—I never would have known my copy of Ikey Owens’ self-titled album came to life in an unconventional way.) And they’ve already made major headway on the artist-recruitment front—everyone from pop songwriter Finneas to psych-prog journeymen King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard have manufactured their records with Good Neighbor.

"It’s really artist-driven," says Coats. "That’s why I jumped in head first. Working with so many artists, there were a lot who didn’t want to make records because of the toxicity. All of my life, I’ve been told there was no other way to do it, and that’s just simply not true. It’s really led by the artists, and if they want to work with us, they find a way with their label or distributor or whoever it may be. This week alone, we’ve had 15,000 records to our customers for Record Store Day [2025], slowly chipping away at what we believe is important. We have a slew of people who believe in us, and hopefully word travels and we’re doing good work and everybody’s happy."

Still, Coats cautions that he’s playing the long game: "It’s gonna be a slow process because it’s a 70-year-old industry that hasn’t been changed." He spoke with GOOD about his own journey to Good Neighbor, the company’s origins, and their ultimate aspirations.

I want to know about your personal relationship with records. How and when did you fall in love with the format?

I started collecting records when I was like eight years old. My brother and sister were going to Jamaica for their senior trip. They asked, "What do you want from Jamaica?" I was like, "I want those little records. Those little things, those small ones. I didn’t even know what they were. They brought me back this stack of reggae 45s, and I’ve been hooked ever since.

Do you remember what they were?

They brought me a couple 12-inches too—"Reggae Sunsplash '1[: A Tribute to Bob Marley], which had a young Ziggy Marley doing the song "Sugar Pie." They got me "Draw Your Brakes" by Scotty from the Harder They Come Soundtrack. I remember Half Pint’s "Greetings" being my favorite as a kid.

Records seem to be the through-line of your life.

Yeah! [Records] sparked my interest in DJ’ing. When I was 10 or 11, we’d go to Skateway, and I’d sit there and watch the DJ instead of roller-skating. I was already intrigued, and I started DJ’ing at 11 or 12, just for fun, and I got into hip-hop and disco and all the samples. I’ve been a record collector since I can remember. Fresh out of high-school, I moved to San Francisco and got a job at TRC Distribution, which was an indie one-stop distributor that did a lot of dance and hip-hop stuff. It’s where Stones Throw started out of. I worked out of the warehouse so I could feed my record habit. [Laughs.]

That’s always nice!

I spent all my money where I worked. From there, I went back down to Southern California because my grandparents were getting older, so I moved back into my mom’s and got a job at Tower Records. I was a buyer there for years for their electronic, hip-hop, and imports section. From there, I got a job with Ubiquity Records as their head of sales and marketing, and I was there for about seven years. After that, I had my first child and decided it was time to get out of the music business because it wasn’t sustainable at the time. [Laughs.] I thought I could leave it and be happy, so I took a job working for a friend of mine selling water ionizers and was miserable. I discovered a band called The Stepkids and sent them to Stones Throw—I had some friends there at the time, and they signed them.

I remember them. Their first album was so great.

There’s a song called "Shadows on Behalf"—when I heard it, I was like, "What is this?" Is this 'Hocus Pocus’? Are these guys new or old?" I freaked out because it sounded like a vintage recording but it’s modern. I sent that over to Gilles Peterson right when I heard it, just on a whim, like, "Hey, I think you would dig this." He played it the next day on Worldwide FM. I was like, "Okay, there’s something here. That doesn’t happen very often." That [connection] led me to a job at Stones Throw for a couple years, and then I went to Innovative Leisure Records as their head of sales and marketing and then spent the last five or six years at Virgin Music as their vinyl marketing director for all of the catalog and distributed labels. I’ve really been surrounded by records and physical media since I started working…30 years ago. Jesus. [Laughs.]

Good Neighbor is intriguing for so many different reasons, including the environmental element and the efficiency of creating the product. What was the initial spark?

Probably two and a half years ago, a friend of mine, Tim Anderson, who was a staff producer and A&R over at Harvest and Capitol when I worked at Virgin and Caroline, was like, "Hey, I want to scrape the oceans of plastic and make records." I was like, "That sounds amazing. Count me in!" As he started going down this path of finding out if we could do that, we met up with a guy who did it, and he was like, "Don’t waste your time. They sound horrible. I had to do them all by hand. There’s no way to clean ocean plastic enough to make a good quality recording." That got Tim sparked on finding if there was another way to do it, and that’s when we discovered these guys in the Netherlands who were using injection molding. The funny thing is that I’d vetted them before as a vendor, but it just wasn’t up to par yet. Tim got in contact with them, and they’re amazing inventors and engineers, but they didn’t have the music contacts that Tim and I did. Tim went to them and said, 'We’d love to be your sales and distribution arm and eventually acquire you. We could come up with a plan to rebrand." They were called Green Vinyl Records, and we were like, 'You’re not using any vinyl in your records. That’s already misleading."

They had an agreement, and Tim called me and said, "Do you want to come work for me?" I said, "Yeah, but I want to make sure the quality is OK." They sent me a bunch of records, and we made a compilation of all our favorite recorded songs and had one made on PVC traditionally and then that same set of stampers made with a PET record and then analyzed the audio form in iZotope, and they were virtually identical. I was like, "OK, there’s something here." That’s when I said, "I’m gonna leave the comfy job and the 401K and the benefits and all of that fun stuff and run this start-up with you."

You seem to really believe in what you’re doing.

It’s something that’s been in the back of my mind for years, knowing how toxic PVC is. Tim had met a woman named Reyna Bryan, our CEO, who came from the consumer packaging world: fixing supply chains for Mars and Pepsi. She’s the real eco-warrior, if you will. She’s the one who vetted this product and said, "This is bullet-proof. They’re not green-washing. This is amazing. I didn’t know people still made records!" She’s not the music person. [Laughs.] Tim basically said, "I need you on my team as co-founder and CEO to run this with me." It was us three in the beginning figuring things out, and then I pulled in [Jonny O’Hara], an old friend from Virgin who was running all the production for King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard and all of the Virgin repertoire—he came onboard as our VP of production. Now we had the scientist who could actually vet the product and talk about how much better it is for the planet. We had Tim and I, who have contacts and could try to convert people into this new format.

It's interesting that you claim to "produce more records per day, per machine, than any major vinyl pressing plant." What’s so specific to your process to make that possible?

Because it’s not using compression. We still have the exact same process up until the actual manufacturing. We still have to cut lacquers. We still have to make plates. But once we make the plates, those plates go into our mold vertically and we inject the PET into the mold, so it’s 180 grams in and 180 grams out. There’s virtually zero waste. The only waste is a little bit of the center. With the injection mold process, we’re doing a full life-cycle assessment right now, and that’s being reviewed by a third-party panel. We want to be able to substantiate these claims for all our customers and artists who want to work with us, but the initial data came back 90% more energy efficient with just the process alone. [The resulting data wasn't available at the time of publication. Coats says it's "coming soon."] That’s because there’s no boiler. We’re not heating up and cooling down plastic and smashing it together. We’re just injecting the exact amount of plastic that needs to go in to make a record, and injection molding is three times faster than a compression hydraulic press.

It seems like there could also be a benefit on the production side for artists. I know many pressing plants have been backed up in recent years and a lot of artists have been struggling on that front.

Absolutely. Once we can get more machines online, that’s when the real changes start happening. We can’t be just this small boutique record manufacturer because then we’re not really doing our job of removing carbon from the U.S. or the world. It needs to be large-scale. As we get more machines online, that’s when we’re really going to see the savings. Our machine can do about 1,500 records in an eight-hour shift, and a standard hydraulic press can do about 500. If we can run two shifts and whatnot, we can knock out a lot of records in a few days.

There are a lot of reasons this could excite people in the industry. Not to be cynical, but there’s also the optics to consider—it looks good to be involved with something like this.

That’s why we’re doing the LCA, so we can actually have the data to back up the claims we’re making. Then the labels and distributors and artists can use that as marketing terms: "By pressing with Good Neighbor, I saved this much CO2 from entering the atmosphere." With Tim, Jonny, and I all being at Universal Music Group for so long, we were fast-tracked in there. They’re big supporters, and we got set up as a vendor, which is really hard to do as a new vendor in a system as big as that. It says a lot about their trust and belief in us, and we appreciate that.

When I decided to come onboard, I was sitting there, thinking, "My entire life of collecting records and being involved in physical media isn’t because I love PVC. It’s because I fucking love buying a record from the band I just saw, going home, capturing that moment when I was there and bought the merch, and listening to the record. I’m reading liner notes, not caring about the compound it was made on. [Laughs.] That was my big epiphany: It looks like a record, feels like a record, sounds like a record—it’s a fucking record. It’s not vinyl. It’s a record. I buy records every day. I still buy records. I’m not here to villainize records. But if there’s a better way to do it and it’s something that I do all day, every day, why not? Honestly, that’s why we called it Good Neighbor: Everyone can co-exist. We’re not gonna win everybody over, and that’s OK. It’s really for at the artist who wants that for their vehicle, for their voice. It’s for filling a void that hasn’t been there for 70 years.

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child  Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Representative Image: It take a special kind of heart to make room for a seventh child

Speaking in public is still one the most common fears among people.Photo credit: Canva

Speaking in public is still one the most common fears among people.Photo credit: Canva muhammad ali quote GIF by SoulPancake

muhammad ali quote GIF by SoulPancake

Let us all bow before Gary, the Internet's most adventurous feline. Photo credit: James Eastham

Let us all bow before Gary, the Internet's most adventurous feline. Photo credit: James Eastham Gary the Cat enjoys some paddling. Photo credit: James Eastham

Gary the Cat enjoys some paddling. Photo credit: James Eastham James and Gary chat with Ryan Reed and Tony Photo credit: Ryan Reed

James and Gary chat with Ryan Reed and Tony Photo credit: Ryan Reed

The military used Henry Johnson for recruitment efforts.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The military used Henry Johnson for recruitment efforts.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons