When artist and author Magali Duzant noticed her father, a native speaker of Antillean Creole and then French, was losing English words, she wondered if it had something to do with aging. It turned out to be dementia. While witnessing a loved one experiencing this is never easy, she also saw beauty in it and even noticed that parts of their relationship deepened. Duzant found herself relating to him, too, as she moved to Switzerland and began learning German, as there were now moments where her own words were not her own. To process his diagnosis she began taking notes on both of their experiences and researching dementia. Eventually she wondered if her ideas could become a book. The result is the art book La vie is like that, also one of her father’s expressions, published by Seaton Street Press in 2024.

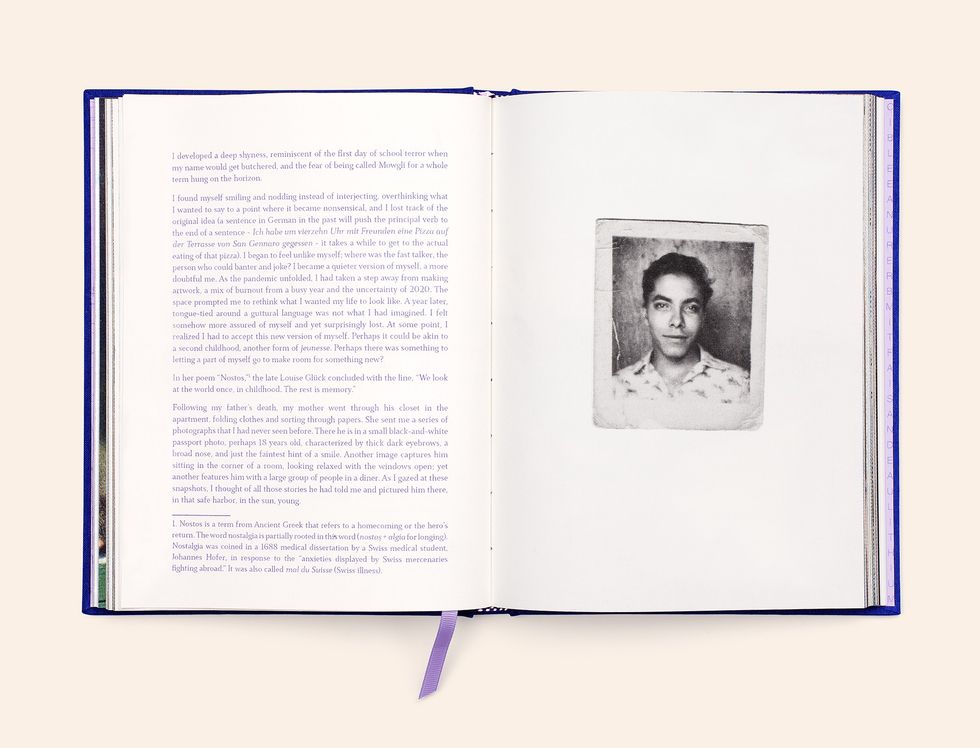

La vie is like that is constructed like a children’s alphabet primer–A is Aphasia and B is for Blumen, for example–but it’s interspersed with personal narratives, history, research, and photographs. It is guided by the principle of the Ship of Theseus, or Theseus’s paradox: if all of an object’s parts are replaced, is it still the same? We go back and forth with Duzant in time in short essays as she explores her father’s life before and during dementia; before and after his passing in 2021; as she understands how language makes us who we are; as she understands that even in its tragedies, dementia can have its own moments of light. With wit and grace, Duzant thoughtfully takes us on her journey with her. In a culture that can be so fearful of dementia’s darkness, she reminds us that the people it affects are never truly gone.

I spoke to Duzant, who is also a dear friend, about La vie is like that, turning lemons to onions, memory, personhood, and more.

How did you arrive at the concept and structure of the book?

I've been working in book format for a number of years now. When we got the diagnosis, I was writing in my own journal to come to terms with it, but also making notes about how he's switching onions and lemons and sand and snow–I thought there was something beautiful and interesting about that. When he died, then it was a way to process his dementia diagnosis, the grief of losing a parent, and not being there when it happened. I had also been researching dementia in general. I wondered if I could share this information because I was so interested in these themes of language: this forgetting, but also this replacement of finding something when a word didn't exist. When my father was still alive, he would forget something or be unable to place a word or term or and I realized I was doing that as I tried to learn German. There was something here and I wanted to talk about it.

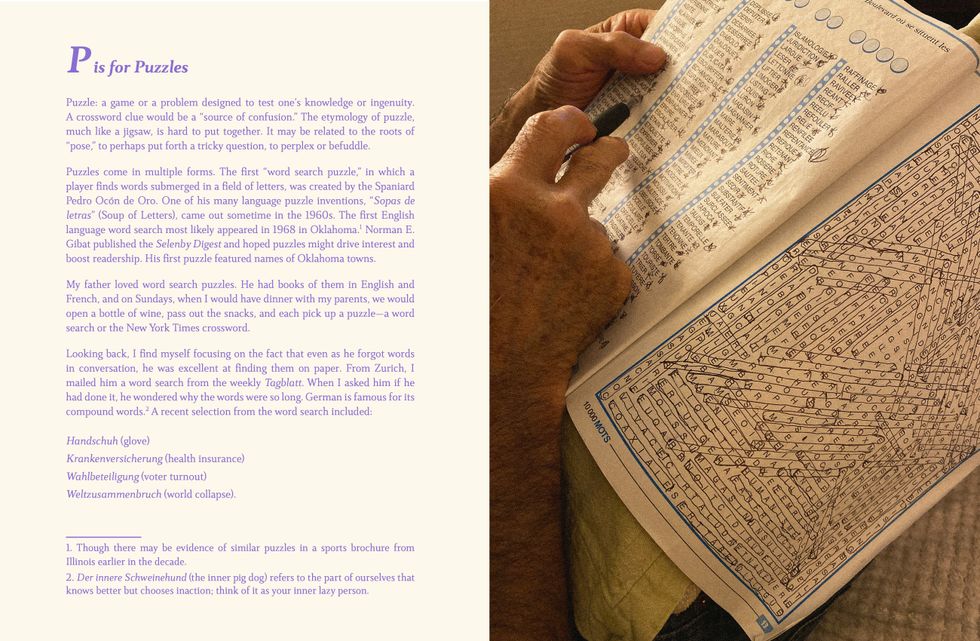

When I told people about my father's dementia, their immediate response was always really extreme, that it must be the most horrible thing. “Does he know who you are?” I realized most people's idea of dementia is shaped by media where it is this horrific, frightful experience, and it is, and it can be, but there's a lot that comes before that. I wanted to respond to that, to my own experience and my father's experience and try to figure out things for myself. I went back to these lists of words I was jotting down–he stopped saying salad and said leaves, and then he lost leaves, and it was paper. There was something about that that was kind of childlike, and that is how I came down to this alphabet guide. I thought this was a great way to introduce these various topics, to link these episodes and essays to make it a bit more approachable and talk about something difficult. I wanted to work with a non-linear narrative because that was how my father was experiencing things.

You mentioned your interest in what happens before the frightening parts of dementia–which ones specifically?

There were parts of my father’s personality that deepened as his dementia became more apparent. That was his goofiness and this mischievous, impishness he always had. He was always very affectionate when I was young, but that deepened in this way that was really beautiful and important. When you can tell you have less time with someone, to have this lovely ease of showing care and affection was only stronger. When people think about dementia, they immediately think of, oh, someone doesn't recognize you, someone can't take care of themselves. Someone's lost all the time. Those are all things that can happen and are heartbreaking and incredibly difficult. But I spoke to my father for an hour every day, at least, when I moved to Zurich. Sometimes I had to follow his bent on a conversation, and sometimes it was a little repetitive or goofy or strange or even a little confusing, but we could have a conversation. He was interesting, he would listen, he could still give me these really wonderful bits of advice. Sometimes he’d say things like he was watching the fish fly by the window, and it was birds. But he was there. I think there is this fear around dementia that is incredibly valid, but also sometimes overshadows that there's still a person there. People change with time and with illness. I wanted to talk about the fact that just because someone is experiencing dementia, and especially early on, they are the person you've known, and they might change a bit, but that doesn't mean that they should be treated as less than or as someone to be afraid of or to pity. I wanted to talk about the fact that my father was still this really lively, interesting person and that I learned so much from him at this time. That was really important because I wanted to share a portrayal of someone that was three dimensional. I didn't feel that I had seen enough talking about even these early stages of dementia or connections like that.

What had you seen in other literature about dementia at the time?

Much of the work I make is influenced by experiences I have. As I was looking around in visual art and photography, I saw so many photographic projects where people in mid-to-late stage dementia were being photographed in these ways I found difficult. I think it's important to see things that are difficult, but what most people see and what they're afraid of is people who are so diminished physically, which happens, but sometimes these people are photographed in this way sometimes feels exploitative. I want to be very careful about that, because I know everyone finds a different way to explore something. But I kept seeing these photo series of elderly people, if they were in memory care facilities or homes and I compared it to how people would respond when I said my father has dementia. I felt, oh, that's what people know of this if they don't know it personally, and that has a role, but I think it also overshadows a more complex view. I had read this book called On Vanishing by Lynn Casteel Harper that was incredibly beautiful and was about the ways in which the language we use in society and the portrayals we see shapes our understanding of dementia and shapes the way we treat other people, that our fear allows us to push people with dementia in shadows. For example, when you're talking to someone, you don't have to continually correct them, maybe just go along with them. Whose experience is taking a hierarchy, and who is saying what that person is experiencing isn't correct, isn't right? That influenced me positively. So much of what I had seen in photography and even in some film, was about the fear and the diminishment that people focus on and there was even less about the arc of dementia.

What was the process of including moments of lightness into the book?

So much of it comes down to, this language that gets used, “he is not there, he's not the same person, who's in there.” Whose reality are we judging or condemning? The humor aspect was so important to me because if we only say this is tragic or horrible, then we force a person into this role, and at times, dementia can be playful. There is a person, you can have a conversation. Why do you have to force someone to say what they’re experiencing isn't real? To a certain extent, it is because it's their experience. So many of my conversations with my dad included us laughing, and it was because he said something and maybe I didn't follow, or because I told him something and he thought it was funny or just because he was playful and loved to joke and laugh. It wasn't about making fun of anyone. It was more about feeling joy, a sense of excitement, and the love of being in someone's presence. That, to me, is so important. That was important in our relationship beforeI knew he had dementia, and still afterwards. I think you can have two things at once. You can have something tragic and have moments of levity. Why deny the moments of humor, of levity, of funny confusion? It's important to find space for connection and for humor and for taking a breath.

How did you want the book to interact with the portrayals of dementia we regularly encounter?

I wanted to look at dementia in a larger context and give some of the background. I wrote the chapter “D is for Dementia,” where I looked at the history of dementia, in terms of its study, but also the way it was discussed from the ancient Egyptians through the “discovery” of Alzheimer's. Then in a larger sense, how can we relate to it? I was lost as I struggled to learn a language, and I had trouble expressing myself fully. I could feel how other people looked at me, because all of a sudden I wasn't expressing myself the way that I could in English, and that was so important. It's not the same, but it allowed me to think about how the loss of language or the being at sea in a language can affect the way one feels about themselves and navigates the world. I think many people can relate to that, whether it's in moving to a new place, language or not, if it's migrating to another country, if it's just kind of finding oneself at sea in any kind of space you don't know. I wanted to allow people to try to find something they might connect with there, and hopefully to find some more empathy through that. Mixing in some humor and some stories of familial connection and frustration, it might open up the conversation.

I hope if somebody is a caregiver for someone with dementia they feel some of their experiences are reflected here. I hope if some people read it and have never met anyone experiencing dementia or have no idea about it, that maybe they'll give pause to how they think about it. I don't want to be language police, but sometimes when people say, ‘oh so and so is demented,’ or, not to make it political, but how people would speak about Biden as “Dementia Joe”--why are you using this as a way to take someone down or as a dig? I hope it helps people have a broader concept of it, to understand a little bit more, even if it’s just that there are different stages, and they shift and reflect. I’d also want people to think about how language is so integral to how we experience the world and how we affect others around us. For me, it was also important that the book didn't shy away from humor. To me, humor is one of the most important things in life, and how do you deal with anything if you can’t laugh every once in a while? I know there are people whose caregiving is so difficult–it's not trying to undercut the seriousness of it. It's also for a population that doesn't know anything about dementia, trying to help people understand that someone experiencing dementia should still be treated like a person, the person you know, and not like a living tragedy.

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper

Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

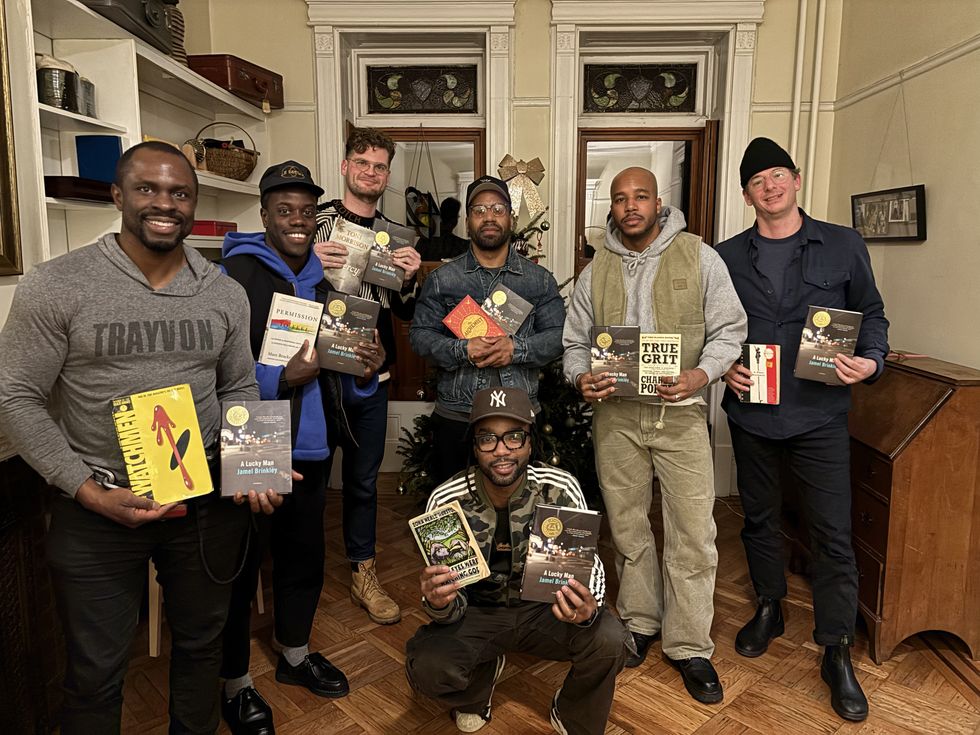

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel