Follow or Get out of the Way: The household name in green construction needs to innovate in order to keep up with the competition.

Imagine if teachers gave out grades on the first day of school based on students' promises of how hard they each plan to study. Oddly, we use this backward system to grade green buildings in the United States.LEED, or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, is the certification system created by the U.S. Green Building Council. The USGBC certifies houses, commercial buildings, and other structures like schools and hospitals, awarding them points for things like interior air quality, proximity to public transit, and energy efficiency. Since 1998, it has been the standard in green ratings for buildings.But LEED's big weakness is that all of its measurements happen on the computer screen before the first bulldozer arrives. According to the USGBC's best calculations, LEED buildings use 25 to 30 percent less energy-while more critical calculations show them as no more efficient, or in some cases worse, than their non-LEED counterparts.Because LEED buildings don't have to perform up to spec in real life, LEED has contributed to a trend of showboating and point scrounging, leaving energy efficiency-arguably the most important metric-lost in the shuffle.The average LEED building doesn't even qualify for an Energy Star label.Amidst a rising chorus of criticism, other standards are finally starting to get more attention. The Passive House standard, born almost 20 years ago in Germany, hones energy efficiency so finely that most certified Passive Houses need no conventional heating boiler. The overall energy use of a Passive House is around 70 to 80 percent less than a comparable conventional building.I toured Passive House-certified buildings in Germany that ranged from homes to schools to gymnasiums. It quickly became clear that-at least when talking about energy-comparing LEED to Passive House is like comparing a Pontiac to a Porsche. And while the Passive House standard doesn't require energy monitoring after the fact (and maybe it should), studies of the nearly 20,000 certified buildings have shown sterling results.If the USGBC can't look at this as a wake-up call, it may be looking at a worthy competitor: Passive House is carving a foothold in the United States among architects and builders who are fed up with LEED or just looking for a new challenge. I've personally spoken to architects who are steering clients away from LEED towards Passive House for reasons of certification costs and energy efficiency.There is even inspiration here at home. Energy Star certification, administered by the EPA, has none of the sexy strut of LEED, but is quite rigorous, and includes actual performance testing. In fact, according to the USGBC, the average LEED building doesn't even qualify for an Energy Star label.But there's hope for LEED, yet. This year, the USGBC rolled out the newest version of its LEED standards, requiring energy and water consumption data for the first five years of a building's occupancy. If building operators don't provide this info, the USGBC can strip a building of its plaque.Finally, the idea that a building's actual performance should determine its grade is gaining traction.

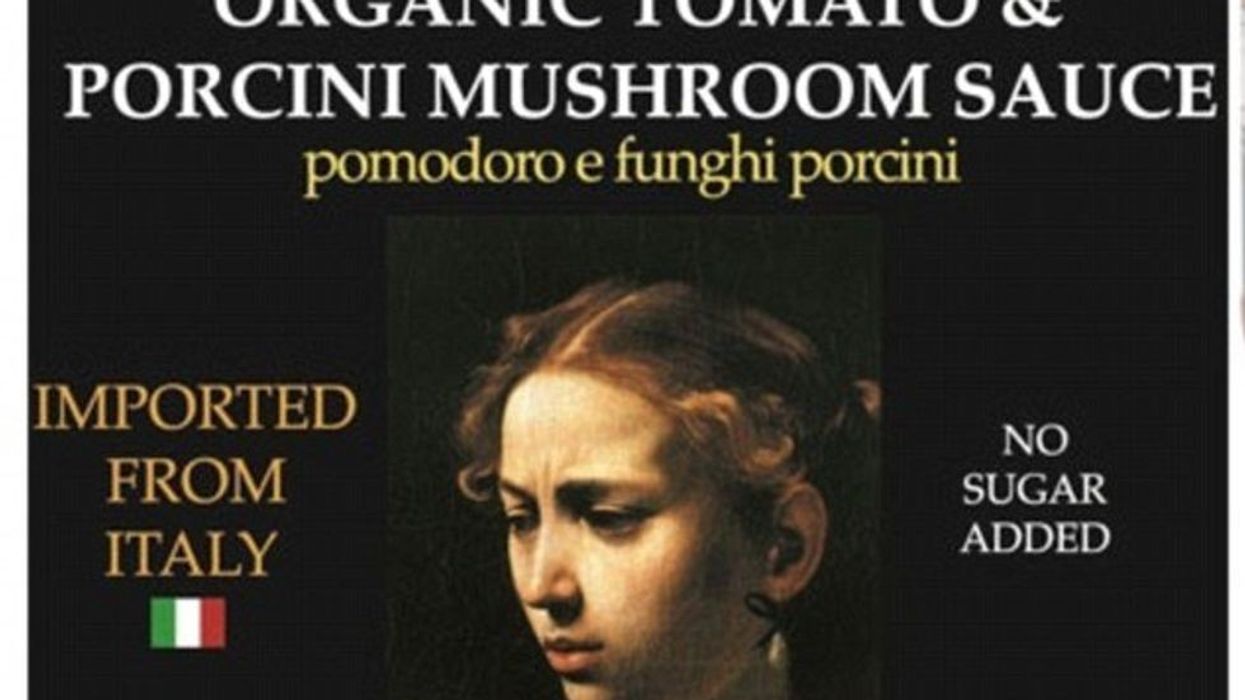

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)