When I first pitched this story, I thought it would be interesting to share an informative biographical sketch of the woman who ideated what was at first called Woman’s Day in the United States. Women's Day was originally celebrated the last Sunday in February--and became the forerunner to global phenomenon International Women’s Day, now celebrated March 8. It also became a lesson in why we celebrate it and celebrate Women’s History Month.

This woman was Theresa Serber Malkiel. According to the Jewish Women’s Archive, she was “the first woman to rise from factory work to leadership in the Socialist Party” in the United States. For decades, she advocated for women’s suffrage, women’s labor rights, and women’s rights to participate in the Socialist Party. She wrote a work of fiction in 1910 called The Diary of a Shirtwaist Striker that was considered one of the inciting influences to factory and labor reform in the U.S. (you can read it online here) and was published a year before the devastating Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911. With her husband, she co-founded The New York Call, a Socialist newspaper, and wrote extensively for it and at least once contributed to The New York Times. In her later years, she advocated for women’s education and even ran for New York State Assembly (it’s reported that she "lost by a small margin").

Still, as I researched her, I learned from historian and scholar Sally M. Miller’s 1978 article “From Sweatshop Worker to Labor Leader: Theresa Malkiel, a Case Study” that Malkiel’s work had largely been unrecorded up to that point. Malkiel had died in 1949 and, as the Jewish Women’s Archive also notes, the headline of her obituary in The New York Times, the paper for which she once wrote, referred to her as “Mrs. L.A. Malkiel, Aided Adult Study: Retired Writer, a founder of Old New York Call–Helped Education Groups.” The obituary touches on some of the above points of Malkiel’s career, but the breadth of her impact was otherwise erased. Indeed, as Miller later wrote, Malkiel was also absent from the American Labor Who's Who and Woman's Who's Who of America published at that point in time, and her letters or archives were nowhere to be found.

Malkiel’s work in labor rights began with her own, fleeing what was then the anti-Semitic Russian Empire of the 19th century, when Jews were essentially driven out of the country. She arrived in New York and began working in factories as many immigrants did. The infamous conditions of factories like these have now been extensively recorded. But, as Miller notes, Jewish single women, like Malkiel was at the time, were often encouraged instead to be homemakers and had little to fall back on when facing treacherous factory conditions. So, Malkiel started her own union, the Woman's Infant Cloak Makers' Union, and found Socialism. “For her, socialism became the path to independence,” Miller wrote, to at least what she believed would be "a cooperative commonwealth of workers which would liberate men and women and establish equality for all.”

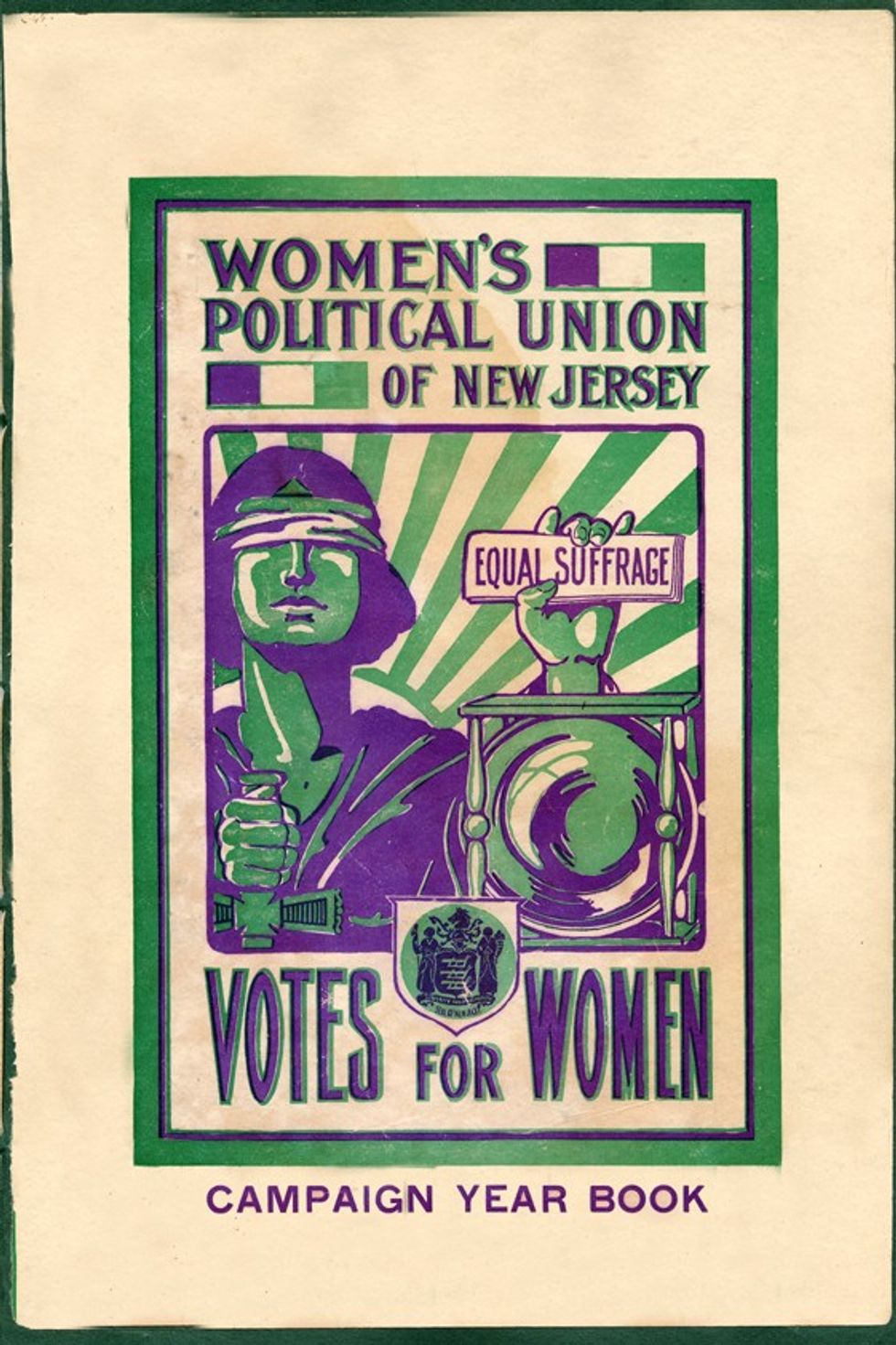

Socialism had to catch up to her a bit, however. Involved in the Socialist Party and the fight for women’s suffrage, she believed that women obtaining the right to vote would only lead to more strength and power amongst workers, that it would ultimately, as the Jewish Women’s Archive shared, lead to women’s emancipation alongside men’s. Unfortunately, the men running the party often delegated women to be “official cake-bakers and money collectors,” as Malkiel put it. They also either didn’t understand why women’s suffrage was so important or didn’t think it was important at all.

Malkiel established and/or led several women’s organizations dedicated to Socialism and later, as previously mentioned, became the first woman involved in Socialist Party leadership. When the Socialist Party did establish a Women’s Department and Women’s National Committee in 1908, Malkiel “was elected to the Woman's National Committee in three of its seven years,” Miller shared. Malkiel advocated for women’s place in the party, also championing immigrant women to learn about worker’s rights. She believed that women could advocate for real change, too, leaving their “cake and money” duties behind if they so desired. But again, the party didn’t always agree with her, and in 1915 the Women’s Department and National Committee were erased from the party. By 1920, Malkiel pivoted slightly but continued her dedication to women’s development by creating the Brooklyn Adult Students Association, promoting the education of adult women.

It would turn out that in all of this accomplishment and advocacy and journalism that the proverbial apple would fall not too far from the tree.

In the middle there, Malkiel also got married–to the attorney whose name she adopted, Leon Andrew Malkiel, and raised their daughter, Henrietta. But Henrietta is referred to as “Mrs. Nelson Poynter” in the Times obituary, so I didn’t actually know what her name was at first, though she was listed as the “co-editor and publisher of Congressional Quarterly.” I looked up the aforementioned Poynter, and it was only from there that I was able to find her, Henrietta Malkiel Poynter, in an article the institute itself had shared in 2018.

Far from being just “Mrs. Nelson Poynter,” Henrietta Malkiel Poynter was a lauded journalist herself, not just writing and editing for Vogue and Vanity Fair, but becoming “a features editor, arts radio commentator and literary agent in New York, Paris and Hollywood,” the institute shared. “She intellectually sparred with people like Charles Lindbergh at glamorous salons,” and was good friends with George and Ira Gershwin, even accompanying George to the City of Light “to find the right French taxi horn, for ‘An American in Paris.’” This was all before she even met Nelson Poynter. Their partnership, in romance and business, began a decade later. She was also involved in the creation of Voice of America, gave it its name and, as the Times did share, co-founded Congressional Quarterly with Nelson. CQ, as it’s known, “was a precursor to C-SPAN, and its example led to modern political and accountability journalism,” the institute wrote. It still exists today as CQ Roll Call. Henrietta Malkiel Poynter received no obituary in The New York Times.

The way we write about women, the way we name them both literally and metaphorically, has changed significantly since both Theresa and Henrietta Malkiel’s lifetimes. To look at Theresa’s life in the context of International Women’s Day is not just to honor her creation what was originally Woman's Day, but to honor lives like hers and Henrietta’s, people who haven’t always been given the credit they deserve or people who have written out of history entirely. The women who built the world, despite anyone trying to stop them, are the reason we celebrate International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month at all.

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: