On a day in 1889, Vincent Van Gogh ordered fresh art supplies from his brother Theo in Paris, including color tubes of cobalt blue, ultramarine, and white, per The Art Newspaper. Theo diligently parcelled the supplies, also adding some “tobacco and chocolate” for the artist. A week later, Van Gogh had finished the painting, today known by the name “Starry Night.” At that time, he considered his painting to be a failure. He never knew, that years later, his painting would be admired in astonishment by the world’s greatest scientists and mathematicians, not only artists. In a TED-Ed video, author Natalya St. Clair explains how Van Gogh’s painting conceals some deep mysteries of movement, fluid, and light.

Currently housed in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), “Starry Night” is a masterpiece of art bubbling with a background palette of blues and yellows. On one side, a yellow crescent moon melts and bleeds, casting a circle of light, almost electric. The cobalt blue sky is flecked with swirling spirals of yellow stars. On a backdrop of glowing starlight, spiraling eddies of wind, and rolling mountains, there is a village painted in the foreground, that sprawls with tiny huts, a church’s steeple, and other architectural elements. The village is surrounded by wavy cypress trees towering in the sky. Clusters of olive trees appear here and there.

Van Gogh painted this masterpiece in June 1889, from his room at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Remy-de-Provence, where he had admitted himself after a mental breakdown. His inspiration behind the painting was the view of sunrise, as he said in a letter he wrote to Theo. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big,” he wrote, per Art & Object Magazine.

Van Gogh considered this painting a “failure.” When the painting was finished, he wrote another letter to Theo saying, “All in all the only things I consider a little good in it are the Wheatfield, the Mountain, the Orchard, the Olive trees with the blue hills and the Portrait and the Entrance to the quarry, and the rest says nothing to me.” However, his painting was far from a failure. It turned out to be a genius work, not just of art, but also of science, physics, and mathematics. It was years later that scientists were finally able to decode the mysteries hidden in Van Gogh’s famous painting. Using breathtaking animations by Avi Ofer, Natalya, who studies art and mathematics, explained how this painting depicts one of the most difficult concepts of fluid dynamics in physics, “turbulence.”

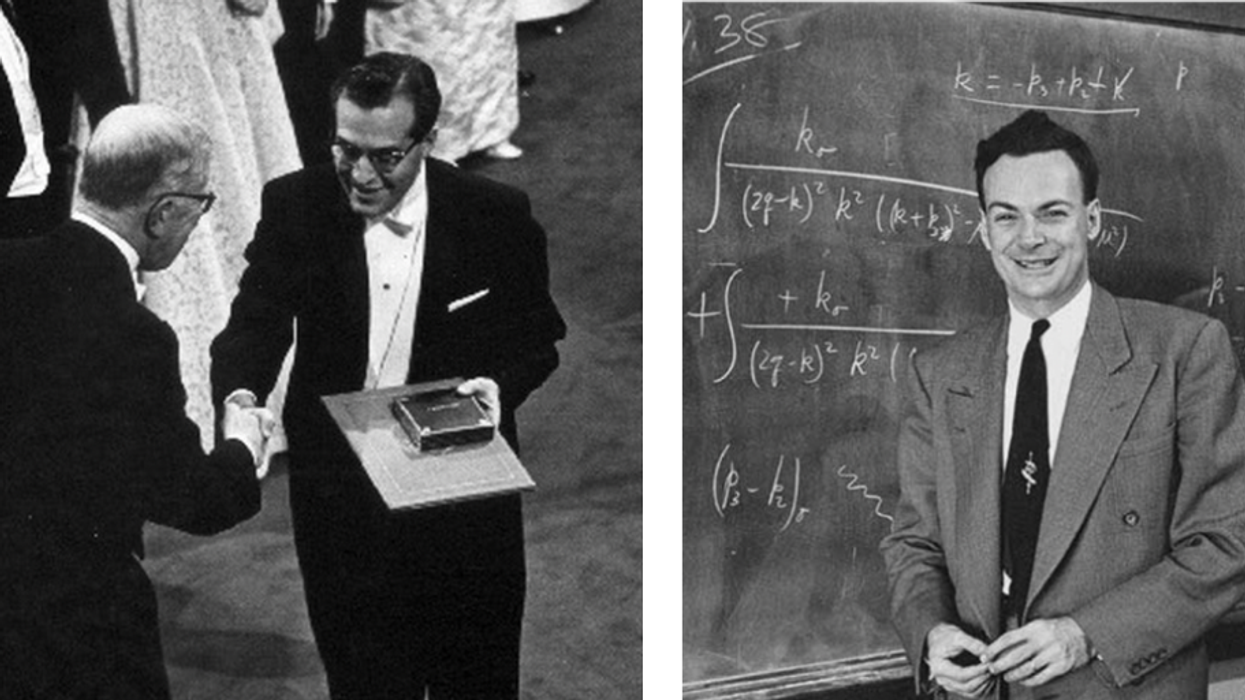

Turbulence is one of the most complex concepts of physics. German Physicist Werner Heisenberg once said, “When I meet God, I am going to ask him two questions: why relativity? And why turbulence? I really believe he will have an answer for the first.” But Van Gogh, intentionally or unintentionally demonstrated this concept on his canvas.

“A turbulent flow is self-similar if there is an energy cascade. Big eddies transfer their energy to smaller eddies, which do likewise at other scales,” explained Natalya in the video. Sixty years after Van Gogh’s painting episode, Russian mathematician Andrey Kolmogorov further elaborated the concept of turbulence as he proposed that energy is a turbulent fluid at length R that varies in proportion to 5/3rds power of R. Apart from turbulence, Van Gogh’s painting also depicts a concept called “luminance.”

Natalya explains that Van Gogh and other impressionist artists represented light in a different way than their predecessors, seeming to capture its motion. “For instance, across sun-dappled waters, or here, in starlight that twinkles and melts through milky waves of blue night sky.” The effect, she said, is caused by “luminance,” the intensity of the light in the colors on the canvas.

In 2004, while some scientists were investigating the night sky using the Hubble Space Telescope, they spotted eddies of a distant cloud of dust and gas around a star and it reminded them of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” They furthered their investigation by studying the “luminance” in his paintings in detail. Stunningly, they discovered that there is a distinct pattern of turbulent fluid structures close to Kolmogorov’s equation hidden in many of Van Gogh’s paintings.

The researchers concluded that the paintings he created when he was psychotically agitated depicted remarkable patterns of fluid turbulence compared to the paintings he created when he was in calmer periods of his life. For instance, his self-portrait with a pipe, from a normal period in his life, showed no sign of these physics concepts. “In a period of intense suffering, he was able to perceive and reflect one of the most difficult concepts nature has ever brought before mankind, including the deepest mysteries of movement, fluid, and light,” Natalya reflected.

During his lifetime, Van Gogh produced more than 850 paintings and close to 1,300 drawings, sketches, and other works on paper. Despite such a large body of work, he wasn’t able to enjoy the fame he deserved for his masterpieces. In 1890, when he was just thirty-seven years old, he shot himself in the chest with a revolver and died two days later. All his work was left to his brother Theo, from whom it was later acquired by the MoMA.

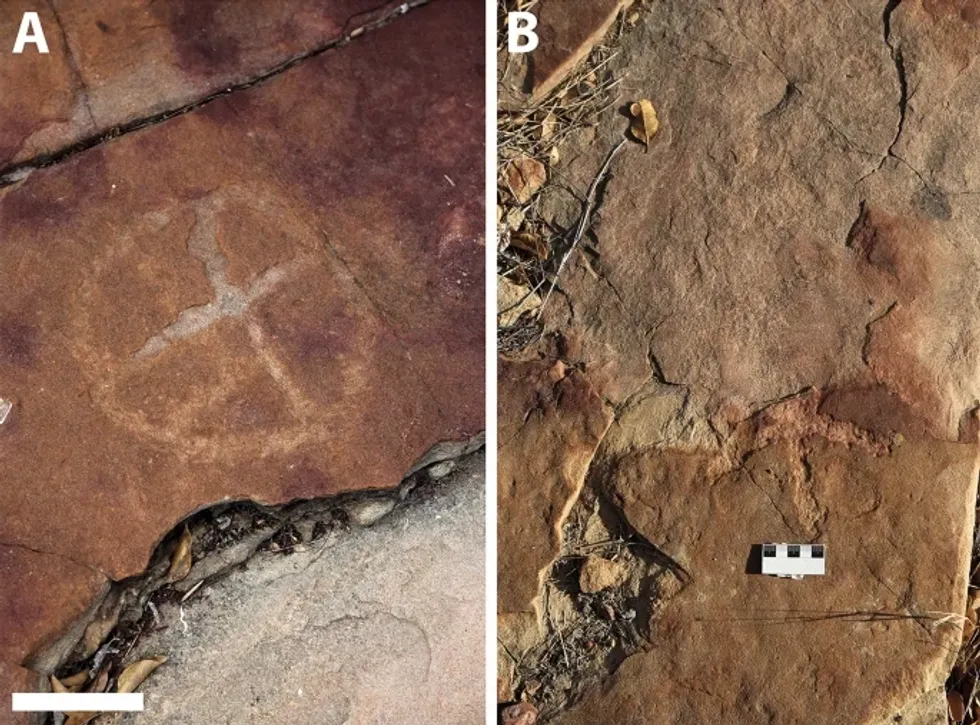

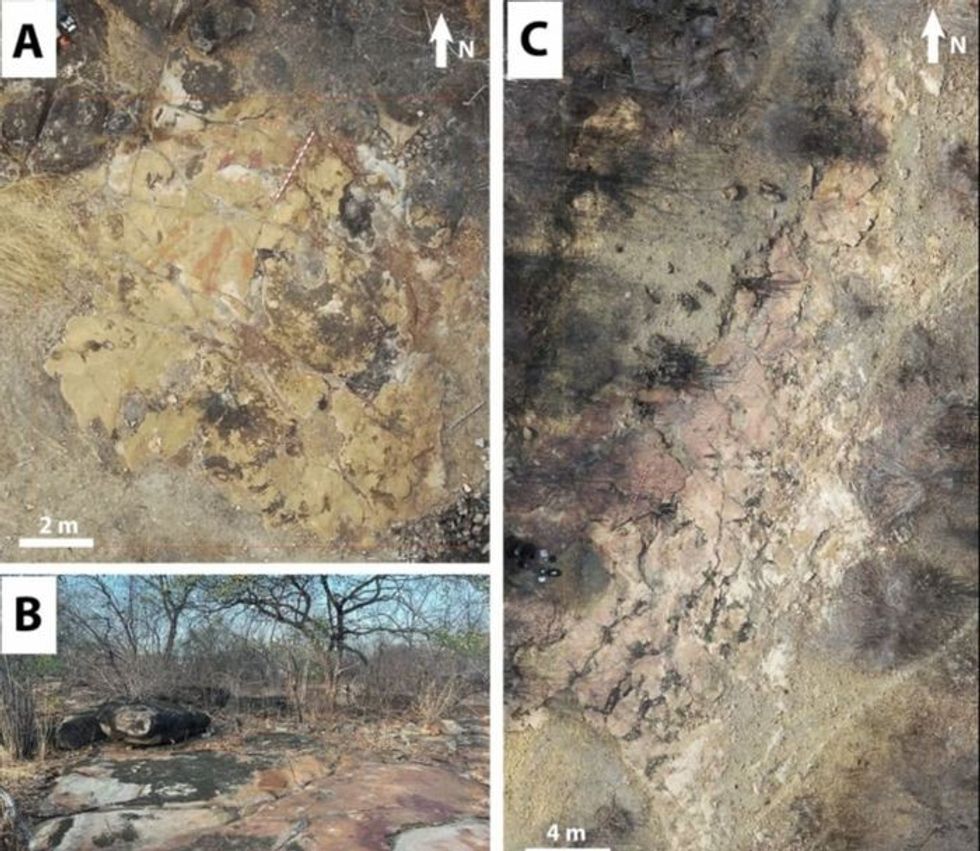

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

Great White Sharks GIF by Shark Week

Blue Ghost Mission 1 - Sunset Panorama GlowPhoto credit:

Blue Ghost Mission 1 - Sunset Panorama GlowPhoto credit: