In 2019, OceanX researchers embarked on an expedition off the coast of the Bahamas, descending hundreds of meters deep in their submarine "Nadir." As they gazed through the sub's windows, the cameras captured a stunning, eerie scene. A massive bluntnose sixgill shark circled the submarine, creating a spine-chilling moment that feels straight out of a thriller. The footage, later shared on YouTube, is a reminder of how little we know about the enormous creatures dwelling in the ocean's depths.

The video, viewed over 25 million times, shows the shark emerging from swirling white vortices around the sub. With an alien-like eye, she peers into the window with a cold, reptilian gaze. She then rolls, flips, and even fiddles with a tagging gun on the back of the submarine. “This is a monster,” one researcher can be heard saying in the video, as the shark appears to inspect the tagging gun on the sub. The undersea beast was about 20 feet long, nearly twice the size of the submarine, according to the OceanX research crew. The goal of the researchers was to attach a satellite tag to the shark.

The clip left many people utterly fascinated with the shark. Many compared it to a sea "monster."@gamecop2191 commented, "Humans: Look at the width of that thing. Giant Monster: *rolls eyes*" and @ManSpider92 added, "That human-like eye is unsettling me. That stare down."

Despite their fascinating nature, little is known about bluntnose sixgill sharks because they dwell deep in the ocean and rarely surface. Though they aren’t the largest sharks—like the long-extinct Megalodon—they predate most dinosaurs and have existed for over 180 million years, according to Newsweek.

These sharks commonly live at depths of between 650 and 3,300 feet, although they have been spotted up to 5,000 feet below the surface. "Approximately half of all living species of sharks on the planet live their entire lives in the deep sea," the lead researcher Dean Grubbs, from Florida State University, told Newsweek. "Yet we know virtually nothing about their biology and ecology. Contrast this with the volumes of scientific information on species like white sharks and tiger sharks. Yet as commercial fisheries globally move deeper, deep-sea sharks are being increasingly caught, particularly as bycatch."

For this expedition, OceanX partnered with Bloomberg Philanthropies, Florida State University, Cape Eleuthera Institute and Moore Charitable Foundation, per NY Post. Though this particular mission failed and they were not able to tag this elusive female shark, in some other missions, researchers have successfully tagged sharks by bringing them to the surface. According to OceanX, Grubbs has been the first to put a satellite tag on one of these mysterious sharks. Yet, for each tagging process, the bluntnose sixgills have to be brought to the surface, as it is physiologically impossible to tag them deep under the sea. Because bluntnose sixgills are a deep sea species, it’s hard on them physiologically to be tagged in this way.

"It is often assumed that these deep-sea sharks would die if released," Grubbs told Newsweek. "We began this project in 2005 to begin investigating whether deep-sea sharks caught and brought to the surface survive if released. Since this time we have tagged more than 20 bluntnose sixgill sharks with archiving satellite tags and another 50 with simple identification tags. But all of these were tagged by bringing the sharks to the surface and tagging them alongside the boat or even bringing them onto the deck of the ship."

OceanX explains on its website that during the typical life cycle of these sharks, they don’t even experience daylight, and very rarely do they feel the low pressure and warmer temperatures of surface waters. After the tagging, the shark doesn’t resume its natural behaviors for some time. Therefore, the data obtained after surface tagging is usually believed to be slightly skewed.

As for the shark seen in the footage, this tag was supposed to remain on her body for three months, before detaching, floating to the surface and uploading the data it collected via satellite link to a processing center where it was meant to be analyzed.

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anni Roenkae

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anni Roenkae Representative Image Source: Pexels | Its MSVR

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Its MSVR Representative Image Source: Pexels | Lucian Photography

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Lucian Photography

Representative Image Source: Pexels | francesco ungaro

Representative Image Source: Pexels | francesco ungaro Representative Image Source: Pexels | parfait fongang

Representative Image Source: Pexels | parfait fongang Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes

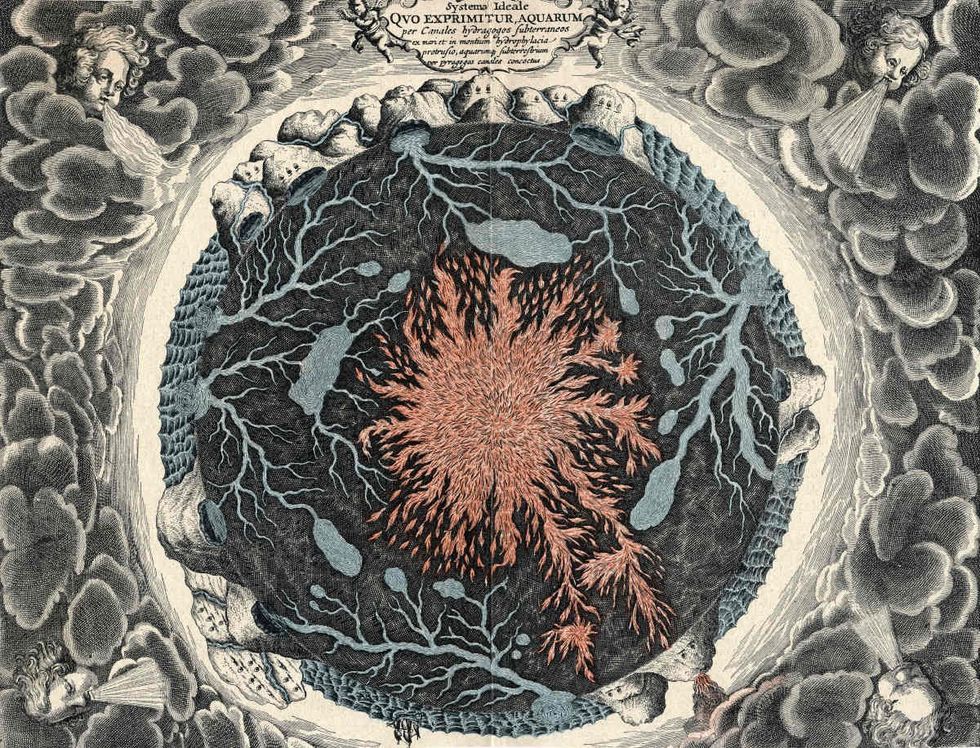

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project

Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack