For a few years, there’s been a rash of videos on social media declaring, “I hate modern art” or comparing “modern art vs. real art.” But as artist J.J. Ellis shares, there’s a bigger danger posed by this negativity to not just to art (modern art is, of course, real art), but to freedom and self-expression.

In a video last week, Ellis discusses a recent controversy around painter Yves Klein’s 1961 work Blue Monochrome and why the painting still matters over 60 years later. In 1961, Artforumshared, “New York artists virtually boycotted his show of monochrome paintings in “International Klein Blue” (his own patented formula of blue) at Leo Castelli’s gallery. The art press, which did not bother to investigate the wider context of his work, found him easy prey.” But the major lesson here, whether or not one is a fan of Klein’s work, is to understand that there’s more than one way of looking at or considering a work of art without dismissing it completely.

The Artforum article goes on to say that the art critic Pierre Restany actually viewed the works as moments of truth and confrontation. “The viewer, in confronting an International Klein Blue monochrome, is staring into the depths of infinite Space/Spirit itself, gazing, as it were, into the coming age of Eden,” the magazine shared.

Which leads us to today, when Blue Monochrome has been making waves on social media again along with other abstract paintings like it. People making videos “with art we think we could have made” offer snap judgments at a glance. Some of those snap judgments of Klein’s work even found their way to Ellis.

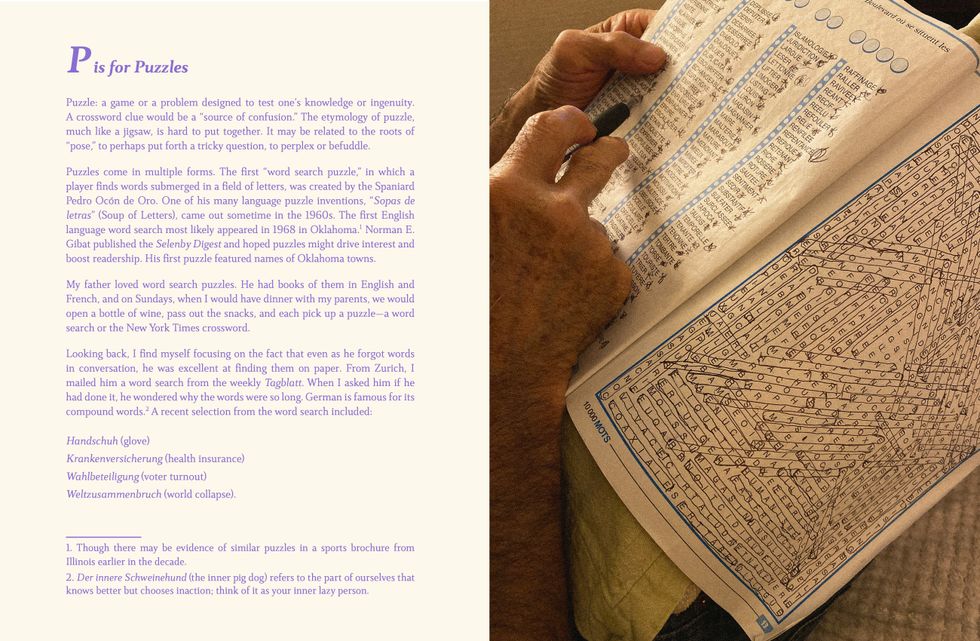

“We need to have a conversation about media literacy. You and me,” Ellis said in a video, having found commenters attacking him because they thought he had made the Klein work. While Ellis is himself an abstract artist, whose bold, vibrant work has appeared in both galleries and private collections, he of course didn’t make the Klein work. Living in a climate of anti-intellectualism is, to say the least, not great for artists of any stripe. But, as Ellis says, while you don’t have to like a work, you should at least first be curious about it—make an attempt to understand it and research it. Doing this becomes essential to perpetuating freedom and self-expression.

As the current presidential administration continues to attempt regulation of creative fields from architecture to theatre to literature and more, art and artists suffer. “We need to take an interest now in the things that are threatened to be lost,” Ellis says. "Art and history cannot be lost to a generation due to the failings of one government." Ellis encourages people to find work that actually does appeal to them, instead of trying to dissuade others from liking entire genres of work. “Read, learn, and grow as a person so that you will understand things that you could share with others,” he says.

Incidentally, there are a wealth of resources out there to help you on your journey to understand different aspects of the art world. The Museum of Modern Art is of course one of them, and offers a series of introductory materials on modern art. And, you’ll be interested to know, modern art and contemporary art are not the same thing–modern art’s time frame is from the 1860s to the 1960s, influenced by the development of modern industrialization, and contemporary art dates to the 1970s. Check out this great video from British gallery Turner Contemporary discussing contemporary art and how to view it as well:

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

An easy way to stand up for art and for freedom of expression is to educate yourself so you can see that art beyond your understanding of the world. past and present. Such efforts can only help us expand our horizons. “After all," Ellis says, "without weird art, society is not a society at all. It’s a regime.”

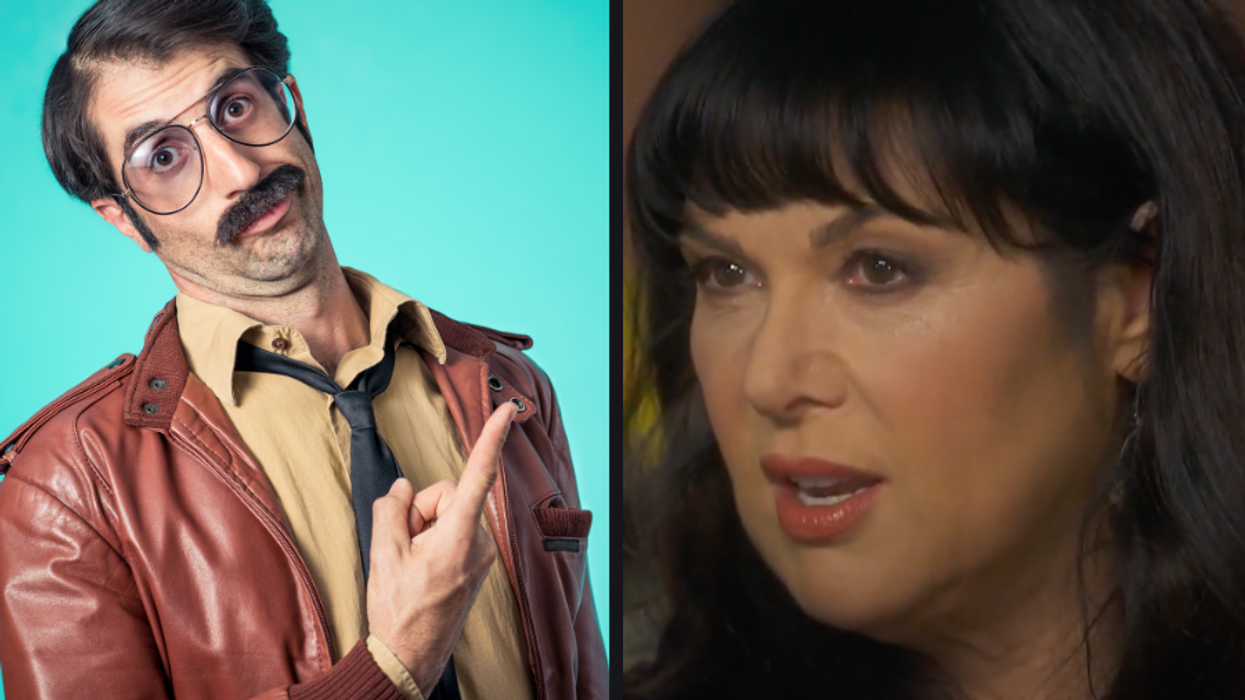

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper

Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

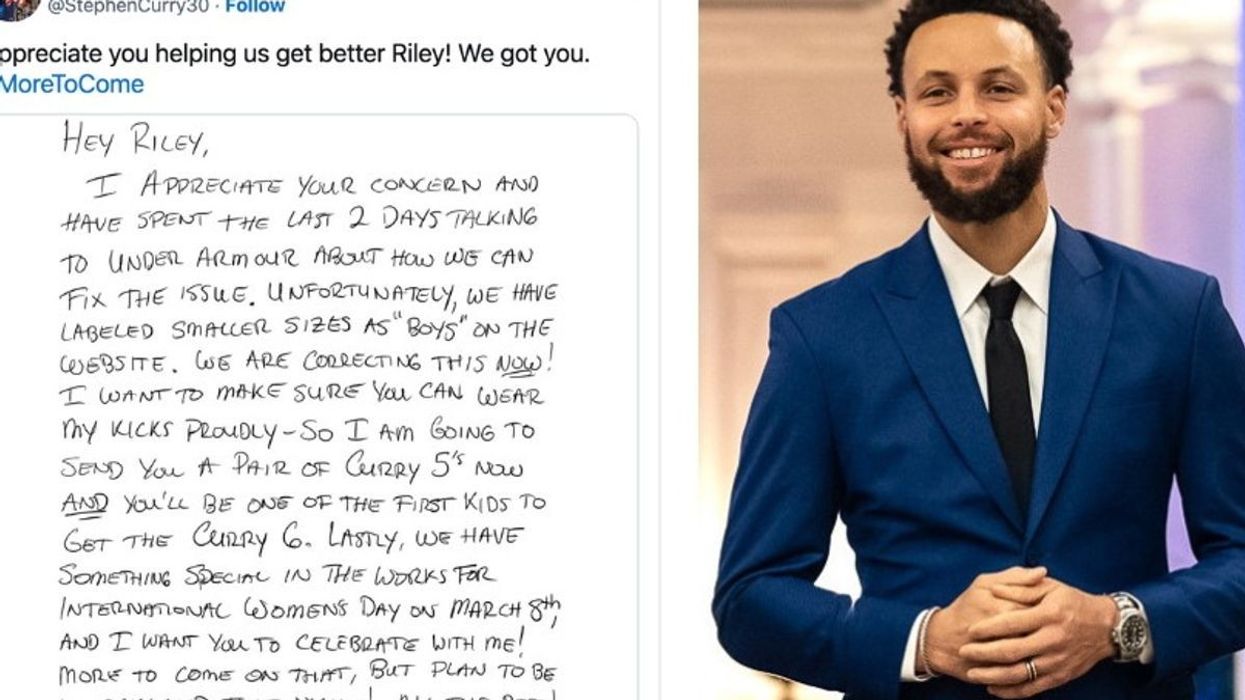

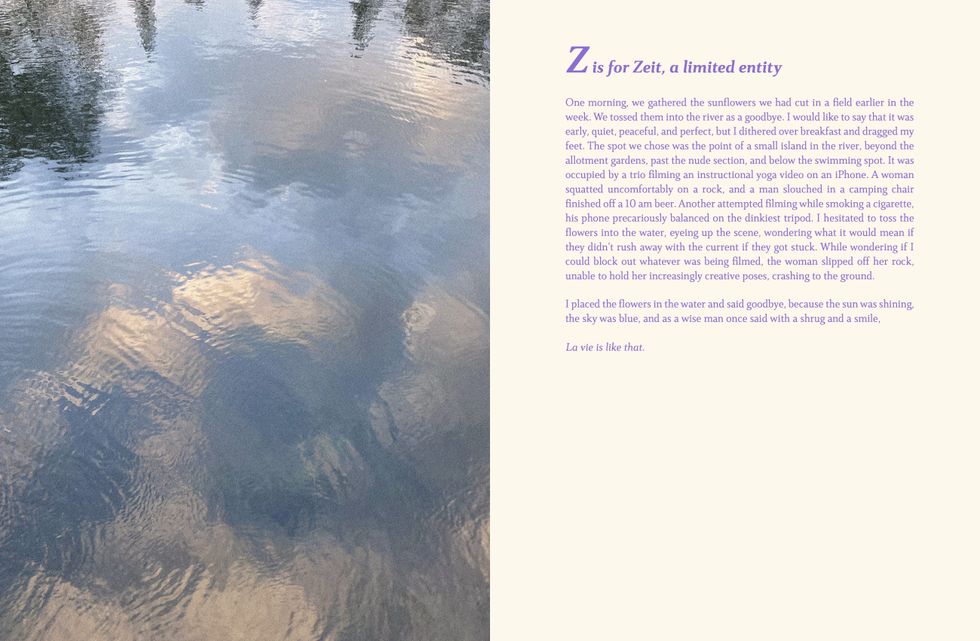

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

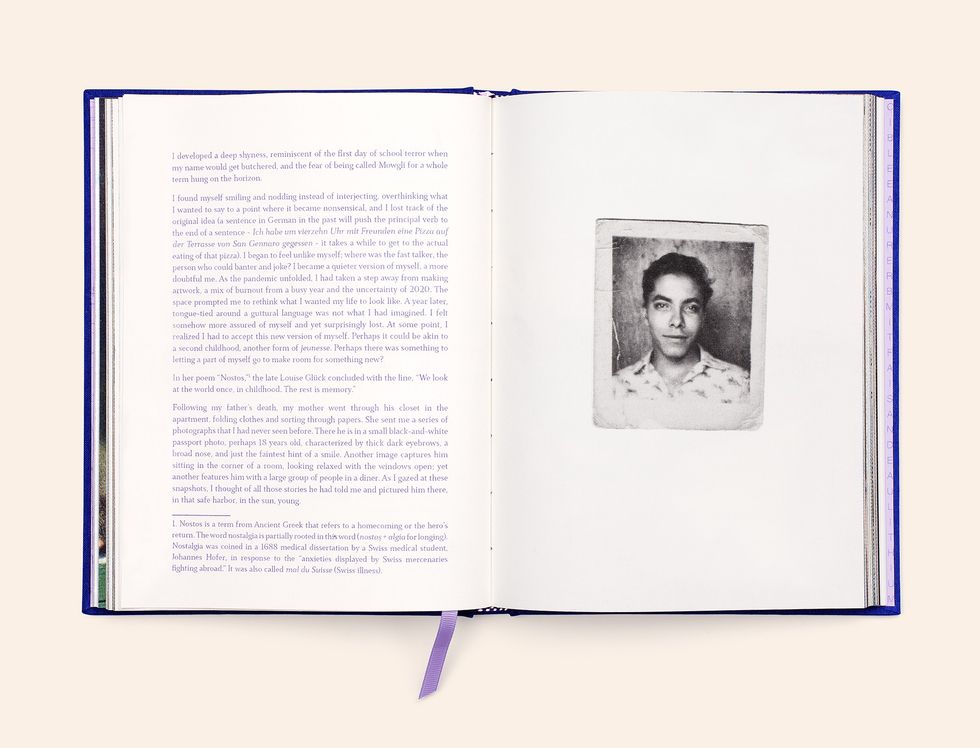

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

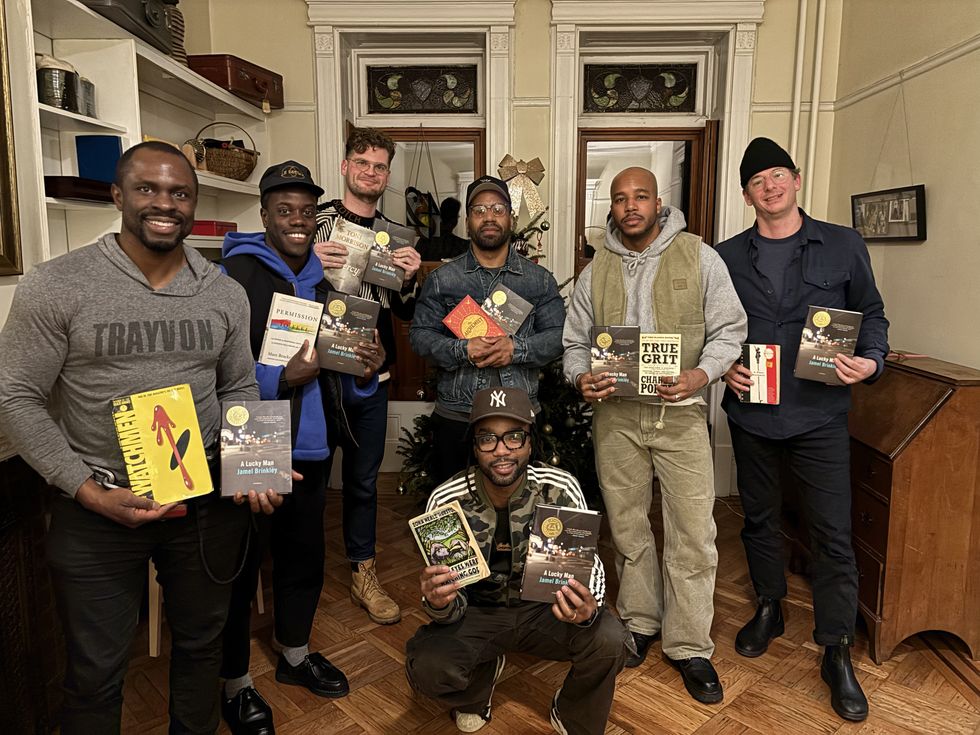

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel