The Great Depression was the “deepest and longest-lasting economic downturn in the history of the Western industrialized world.” Today, the devastation of the Depression feels safely cushioned by history and the New Deal acronyms I could never remember in social studies. But in this moment of Donald Trump’s election to the presidency, a moment which will certainly be copied down in history books, it bears remembering that history is made up of stories—our own stories. My grandmother grew up the youngest of seven first-generation children in Chicago during the Great Depression. Her father and older siblings waited in lines every day for temp work that would earn mere cents. Finding enough food was a daily challenge.

In 2009, theOhio Department of Aging solicited stories from those who had lived through the Great Depression. Coming off of the 2008 financial crisis it seemed, I think, a last chance to learn something from the generation who lived through the Great Depression as they reached their 80s and 90s. The stories are highly varied; some tell of parents struggling to feed their children; some of difficulty in finding secure employment; some of insufficient supplies for school. For many, that was the reality. It is the narrative of the Depression we are most familiar with, but of course, there are many.

Berkley Bedell was born in 1921 in Northwest Iowa. The Great Depression lasted from 1929 to 1939—Bedell was 8 to 18 years old throughout its duration. He is a six-term congressman, the first-ever National Small Business Person of the Year award recipient, and a published author. I am lucky that he also happens to be a friend of my grandfather’s. When I spoke to Bedell over the phone, I’d already had a chance to look through his book,Revenue Matters: Tax the Rich and Restore Democracy to Save the Nation in which shares his politics and gives some of his background, including the fact that he started his award-winning business during the Great Depression.

In 1936, when Bedell was 15, still in high school and three years away from the end of the Depression, he started his fishing business, Berkley and Company, with $50 he had saved from a paper route. He spent roughly half on supplies to make fishing flies and fishing leaders and the other half on an advertisement. By the time he graduated high school in 1939, he had three women working for him for 15 cents an hour each. He promoted his business by traveling the Midwest taking orders. As he recounts in Revenue Matters, “I traveled over 3,000 miles and spent less than $50 for the entire trip—for 20-cents-per-gallon gasoline, 5-cent milk, and 5-cent bread.” The same business that Bedell started with $50 during the Depression would go on to win him the first ever National Small Businessman of the Year award from President Lyndon Johnson in 1964, and it is today a prominent fishing supply company.

I asked him whether he thought, in hindsight, that the Depression affected his business, and he told me that because he had such a small part of the total industry at the time, he was lucky to be unaffected. Instead, those that had to pay employee salaries and pay for their storefronts were more severely impacted. At the time, he didn’t realize what a tremendous opportunity he had. While his competitors struggled in tough economic times, Bedell had no overhead costs—he operated out of his parents’ house and the 15 cents per hour he paid his employees was not regulated by a minimum wage. The women working for him were just glad to have the money.

Bedell grew up in a rural community 500 miles away from Chicago (where my grandma’s family was struggling to survive) and 1,300 miles away from Wall Street where the stock market crash spelled nationwide economic decline. “In rural communities, people did not go hungry, did not lack shelter,” he said. He knows that times were hard, that people were poor, but he told me how much less people needed at the time. In Revenue Matters he says, “Most everyone was relatively poor by today’s standards, but we worked together with what we had and life was good.”

Bedell explained how, without television, kids made their own fun and played outside. People lived a more active lifestyle. “Humanity has made great advances in science, technology. Life is much easier, but I’m not sure it’s better.” He noted that his experience was atypical in many ways. He started what would become a very successful business. His father was an attorney and made more money than most. Given Bedell’s relative wealth during the Depression, it would be tempting to think that he was an outlier in his belief that life was better in the early 20th century, but responses from the Ohio Department of Aging’s survey show that many who lived during the Great Depression agree with his assessment. In the same paragraph that respondents detailed their hardships, they lamented that modernity—internet, TV, exorbitant wealth—has come at the cost of self-sufficiency, generosity, and simplicity.

Bedell acknowledges the possibility that he’s being nostalgic, but he’s quick to point out the problems we face today that weren’t a concern during his childhood: climate change, the threat of nuclear war, the breakdown of political parties. When I asked how the economy eventually turned around, he told me that when the government intervened to create jobs, the economy started to recover. He credited the programs Franklin D. Roosevelt created to provide jobs (collectively what would become The New Deal), but said that the economy did not fully recover until after World War II, when the war effort stimulated the economy. He believes that government intervention is again key to our economic future. He believes in redistributing wealth and power by taxing the wealthy and eliminating corporate America’s political sway—lessons he’s learned since he was 15, starting his own business and watching as the country emerged from the Great Depression.

When I initially told Bedell that I wanted to share a firsthand account of what it was like to live through the Great Depression, he asked if he could give me some advice, as a writer and as someone “who’s lived in the world longer than most.” In so many words, he suggested that I not rely on a narrative I was expecting to hear. “From what I’ve seen,” he told me, “it’s worse today.”

In the current political climate, it’s easy to be nostalgic for a simpler time—I wish that the election of a new candidate did not bring up worries for the planet’s safety, for people of color’s safety, for the safety of programs and organizations that so many rely on.

That said, at the start of the Great Depression, women had only earned the right to vote nine years earlier; schools wouldn’t be legally desegregated for another 25 years; and the polio vaccine was still 26 years from approved use. It was a time when you could start a business with $50 in your pocket, before getting your college degree, but also an era fraught with financial hardship that left many Americans starving and without work. There are lessons to be learned from the Great Depression—nearly 80 years later, Bedell still believes strongly in equal distribution of wealth. And given the events of the last few weeks, I am hopeful that we can learn lessons from the past without forfeiting the progress we’ve made, without forgetting that we still have so much work left to do.

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Olly

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Olly Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay Representative Image Source: Pexels | Cottonbro

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Cottonbro Representative Image Source: Pexels | Cottonbro

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Cottonbro Representative Image Source: Pexels | Karolina Grabowska

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Karolina Grabowska Representative Image Source: Pexels | Jonathan Borba

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Jonathan Borba Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |  Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |  Image Source: Reddit |

Image Source: Reddit |

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Pixabay Representative Image Source: Pexels | markus winkler

Representative Image Source: Pexels | markus winkler

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Shvets Production

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Shvets Production Representative Image Source: Pexels | Oleksandr P

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Oleksandr P Representative Image Source: Pexels | Photo by Spencer Selover

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Photo by Spencer Selover Representative Image Source: Pexels | JSME Mila

Representative Image Source: Pexels | JSME Mila

Representative Image Source: Wellington boots in a row in hallway (Getty Images)

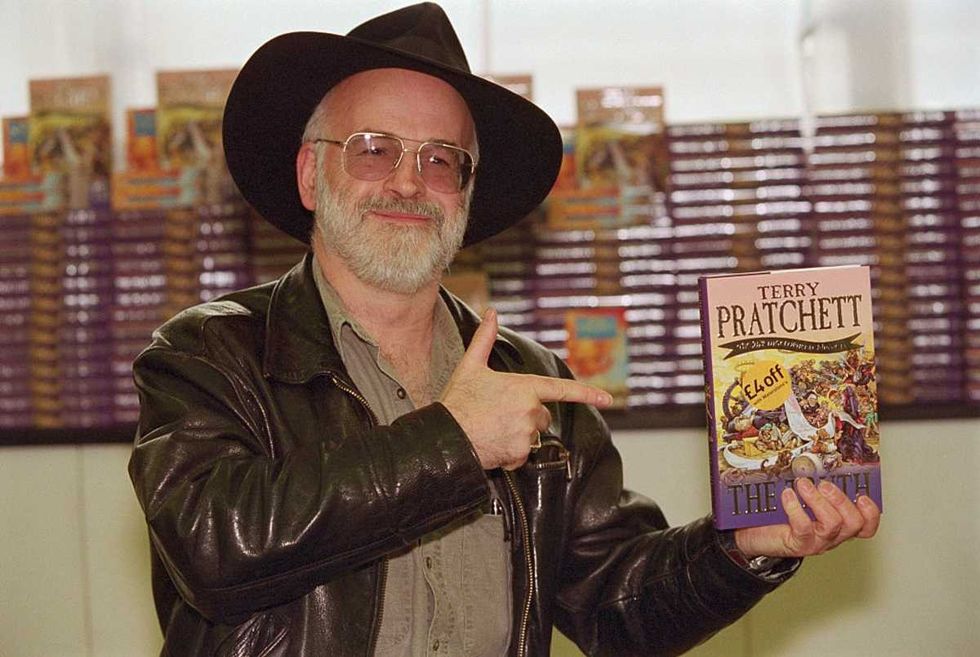

Representative Image Source: Wellington boots in a row in hallway (Getty Images) Image Source: Writer Terry Pratchett Pointing to His Book (Photo by Rune Hellestad/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Image Source: Writer Terry Pratchett Pointing to His Book (Photo by Rune Hellestad/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Pexels| RDNE Stock Project

Representative Image Source: Pexels| RDNE Stock Project Representative Image Source: Pexels| Satoshi Hirayama

Representative Image Source: Pexels| Satoshi Hirayama Image Source: TikTok|

Image Source: TikTok| Image Source: TikTok|

Image Source: TikTok|

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Max Fischer

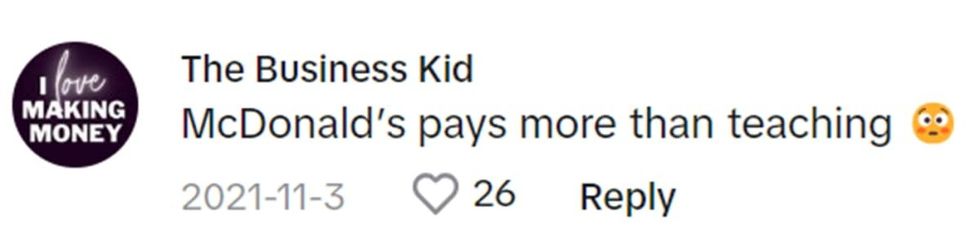

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Max Fischer Image Source: TikTok |

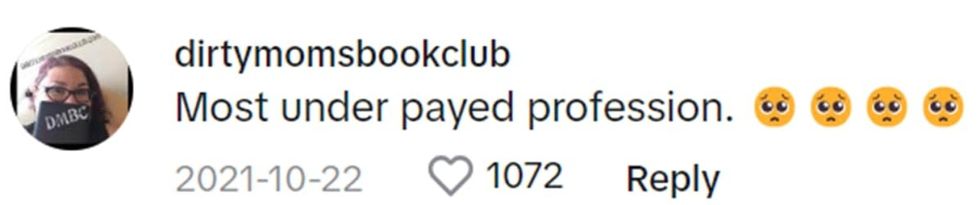

Image Source: TikTok |  Image Source: TikTok |

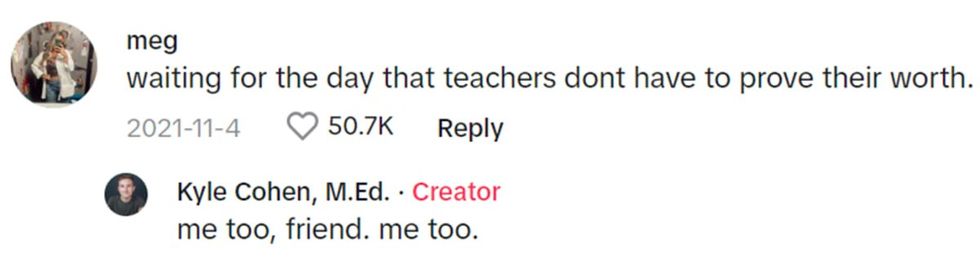

Image Source: TikTok |  Image Source: TikTok |

Image Source: TikTok |