Adorable photos and videos of pets are just a scroll away on social media nowadays. But ever wondered what the earliest pet portraits must have looked like? The National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, U.K., has unveiled what are believed to be the earliest pictures of pets captured on camera. This collection dates back to the 1830s and includes the prints of a picture of a cat, captured by photography legend William Henry Fox Talbot, as well as an 1847 photo of author Mary Mitford’s dog.

The pets had to lay still for about 3-4 minutes for the picture to be captured by antique cameras from that time. Talbot used negatives to create images known as "calotypes." This process was introduced by the photographer himself and involved using silver iodide on paper to create pictures.

Author Mary Milford was one of the earliest people to adopt this method and the photo of her dog is one such example. Talbot's cat image was created by using the calotype method and was a recreation of the picture, “A Favourite Cat,” by artist J.M. Burbank, who was popular for his animal pictures in Britain during the 1830s.

Curator Ruth Quinn pointed out that various photographic procedures were used to capture the images of beloved pets, ranging from calotypes to daguerreotypes. As per the Library of Congress, "The daguerreotype is a direct-positive process, creating a highly detailed image on a sheet of copper plated with a thin coat of silver without the use of a negative." One of the images released by the museum is a daguerreotype of a dog who must have moved during the process, resulting in a blurry picture. The method was developed by Louis Daguerre.

The "cabinet card" trend also emerged during this time which had small images on cards to share with family and friends. These were a popular way of sharing images of pets back in the day. This just goes to show that people have adored their pets just the same across centuries and have had a deep desire to make and share pictures of their furbabies, much like today. The key difference was that these processes took much more time and effort back then and much more patience on the pet subject's part as staying still for 4 minutes is no joke, neither is having wasted film and bad pictures when the procedures of producing one were so complicated.

Now, how the photographers managed to keep the pets so still is a mystery to this day. But because of their efforts, we're able to witness the evolution of pet pictures over time. "These days, we’re more likely to snap our favorite pets using our phone cameras than time-consuming film processes—but the impulse to capture photos of our furry friends remains the same," Quinn echoed the sentiment.

A symbol for organ donation.Image via

A symbol for organ donation.Image via  A line of people.Image via

A line of people.Image via  "You get a second chance."

"You get a second chance."

36 is the magic number.

36 is the magic number. According to one respondendant things "feel more in place".

According to one respondendant things "feel more in place".

Some plastic containers.Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich

Some plastic containers.Representational Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Nataliya Vaitkevich Man with a plastic container.Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Man with a plastic container.Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kampus Production

Canva

Canva It's easy to let little things go undone. Canva

It's easy to let little things go undone. Canva

Photo by

Photo by

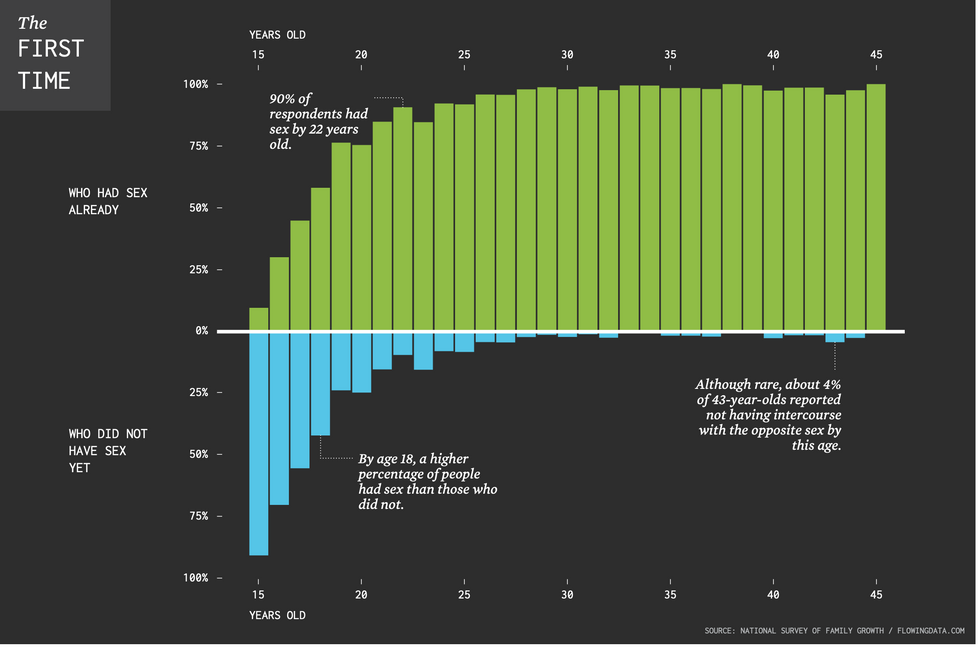

Teens are waiting longer than at any point in the survey’s history. Canva

Teens are waiting longer than at any point in the survey’s history. Canva Chart on the age of a person’s first time having sex.National Survey of Family Growth/flowing data.com | Chart on the age of a person’s first time having sex.

Chart on the age of a person’s first time having sex.National Survey of Family Growth/flowing data.com | Chart on the age of a person’s first time having sex.