Humans experience vivid sensations through millions of touch receptors in the skin. When touched, these receptors send signals to the brain, triggering various reactions—one of which is tickling. It often causes people to squirm or laugh uncontrollably. However, a 2022 study in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B reveals why people can’t tickle themselves, and the explanation is fascinating.

Typically, human bodies have a “comparator mechanism,” with which their brains can differentiate between self-touch and the touch of others. Just imagine how differently someone’s body reacts when a masseur rubs, and massage their skin as compared to when they try to massage their body by themselves. When it comes to tickling, science has proven that people react with much more intensity to others tickling them. This is how babies first learn to distinguish between their bodies and their parents’ bodies. But when one tickles oneself, the body suppresses the sensations that would otherwise be triggered if another person tickled them.

Neuroscientist Michael Brecht from Humboldt University, who led the research, told WIRED that tickling “is a very strange kind of touch and reaction to touch.” And even though the playfulness humans feel through tickling can fade with age, it doesn’t lose its mysterious nature. During the study, his team involved a group of twelve participants who were grouped further in pairs. In each pair, one person took the role of tickler and the other became the ticklee.

While the ticklees were seated comfortably, ticklers were stationed at the required positions. Meanwhile, using GoPro cameras, the researchers meticulously recorded the participants’ responses and reactions after getting tickled. The sounds they made while getting tickled were recorded in microphones, while a respiratory belt transducer measured their chest diameters as they were being tickled. Each body part was to be tickled five times. “Ticklers were instructed to keep the tickling short, using their thumb, index and middle finger, and to limit tickling to one tickle event per trial. Ticklees were told to act as naturally as possible, that is not to force but also not to withhold laughter,” the researchers described in the paper.

After the initial experiment, participants were asked to tickle themselves while researchers tracked their reactions. After the experiments were over, the researchers examined the videos recorded in their cameras to investigate the reactionary phenomenon of tickling more deeply. Their first observation was that a person’s facial expressions and breathing changed about 300 milliseconds into a tickle. The ticklee’s cheeks were raised and the corner of their lips were pulled outward, combining together to form a smile. Then, at about 500 milliseconds, came the vocalization response. On the other hand, the self-tickling was uneventful and less intense. The occurrence of the ticklee giggling dropped by 25 percent and was delayed to almost 700 milliseconds when self-tickling. “It was a surprise to us,” Brecht told WIRED. “But it’s very clear in the data.”

The team explained in the paper that ticklishness is usually of two different kinds. One called “knismesis” is “a touch that is light and feathery, like a spider crawling upon one's skin,” whereas, the other called “gargalesis” is “heavy and rhythmic, and commonly associated with playful and interactive behavior.” They add that while knismesis may be self-evoked, gargalesis occurs only in response to touching certain parts of the body. “It is the only form of touch that provokes laughter, placing it in a unique position of the behavioral repertoire.”

But why does self-tickling feel less joyful than when others tickle? Brecht told WIRED that one reason could be the “prediction” ability of the brain. Self-touch is always predictable and hence, it arouses no reaction from the body, while the touch from the other is an intricately unpredictable sensation for the body. Adding to this, Brecht said that when one touches oneself, there is a suppression or inhibition of the sensations that would otherwise arise if someone else touched it.

Explaining this inhibition process, Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore at University College London told BBC, “Whenever we move our limbs, the brain’s cerebellum produces precise predictions of the body’s movements, and then sends a second shadow signal that damps down activity in the somatosensory cortex – where tactile feelings are processed. The result is that when we tickle ourselves, we don’t feel the sensations with the same intensity as if they had come from someone else, and so we remain calm rather than writhing with that familiar mix of discomfort and pleasure that comes when someone else tickles us.” After this study, Brecht’s team plans to continue unraveling the neuroscience of touch, ticklishness, and playfulness.

A pair of scissors.

A pair of scissors. A can opener opening a tin can.

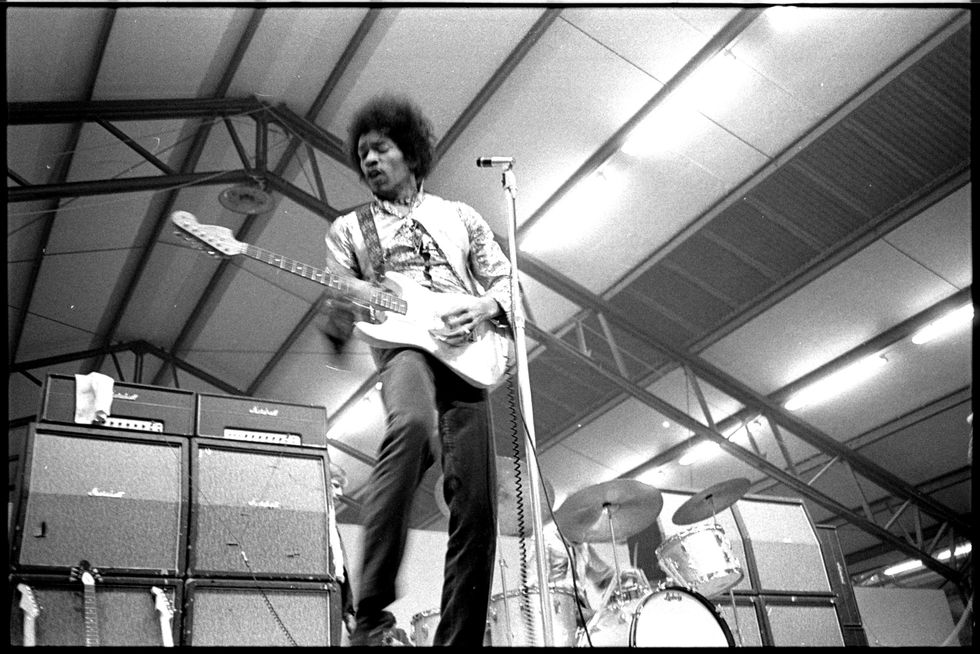

A can opener opening a tin can. Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain

Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain A man handing over $20 in cash.

A man handing over $20 in cash. A person using a power saw.

A person using a power saw.

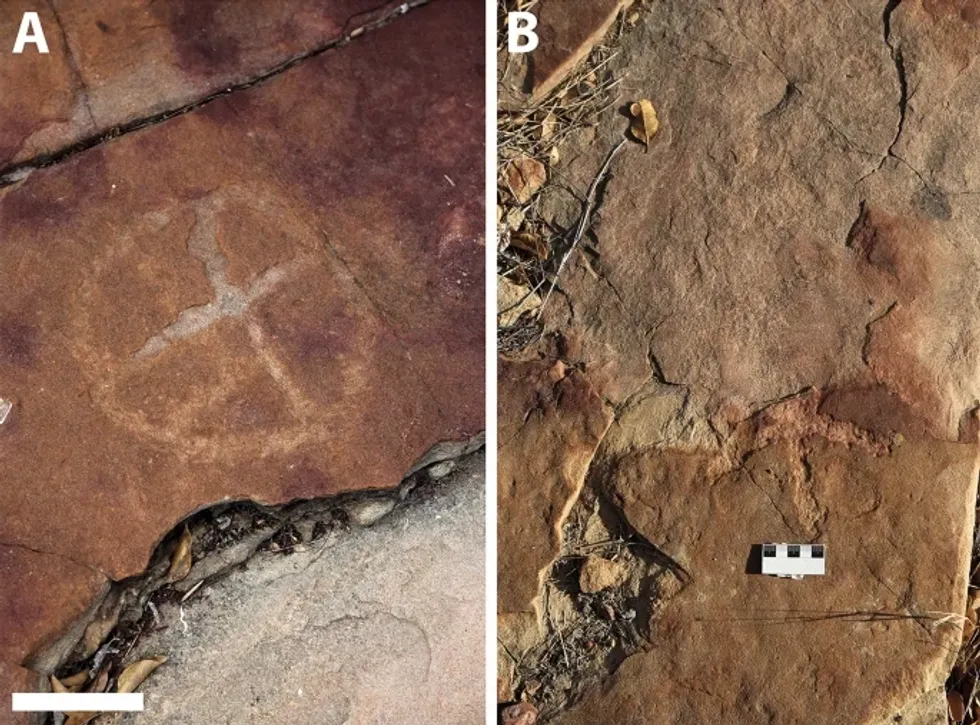

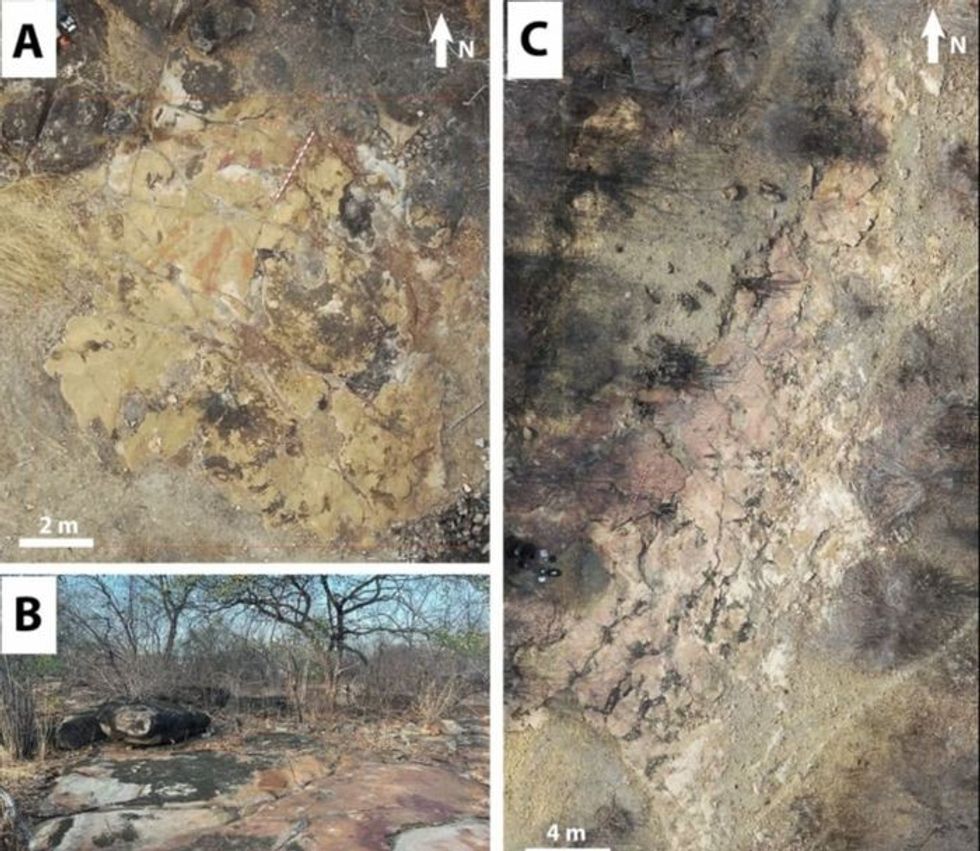

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva

Music isn't just good for social bonding.Photo credit: Canva Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva

Our genes may influence our love of music more than we realize.Photo credit: Canva