When Chefs Norma Listman and Saqib Keval opened their restaurant Masala y Maíz in Mexico City, the plan was not just to honor their cultural, culinary backgrounds but to create a new kind of hospitality. They’d have good food and a good restaurant, of course, but they also wanted to show having a life, valuing their staff, giving credit where it’s due, and creating community were not mutually exclusive. Listman and Keval have been able to realize their vision, creating dishes that draw from Mexico, East Africa, and South Asian cultural traditions. It’s a mestizaje, “an organic blending of cultures over generations often in response to colonization & displacement,” they write. Their restaurant has since become lauded the world over, named one of the world’s 100 greatest places, the subject of Netflix’s most recent Chef’s Table season, and so much more.

Listman and Keval always wanted to decolonize what a restaurant could be from traditional Eurocentric ideals. It also became clear they wanted Masala y Maíz to be a feminist restaurant. “Decolonization and feminism go hand-in-hand. I don't think you can have one without the other,” Listman says. “You cannot have a feminist fight without fighting racism and systemic oppression.” Listman, who was born in Mexico but moved to the U.S. to work for many years, returned home in 2016 and came face to face with Mexico’s powerful feminist movement partly in the form of their large-scale International Women’s Day march. Last year, for example, 180,000 women took part to stand up for their rights, protesting violence against women. Masala y Maíz had been open on March 8th, the day of the march, to celebrate the day with special meals, but Listman realized she wanted to be at the march herself. So instead, for the last three years, Masala y Maíz has shut down on March 8th to become a safe haven for protestors. This year, they will also be celebrating the day before by hosting a dinner run by lauded female chefs Isabel Coss, Ana Castro, and Catalina Londoño Ciro.

GOOD spoke to Chef Listman about the International Women’s Day march, running a feminist restaurant, decolonizing vanilla, and driving your own narrative.

What was your first exposure to the International Women's Day March and Un Dia Sin Nosotras in Mexico?

The march has been growing and growing. In the U.S., I didn't feel identified with the white feminism of the Global North. I came back home, and it hit me how big this was. The feminist movement had been happening for a long time here in the Global South, especially in Latin America. There are 10 women that are killed every day in Mexico that go unnoticed, where there are no consequences. The reality for us here is very different, and I feel a different sense of responsibility, also being a business owner and being in charge of a team that at one point was mostly women. Right now, it's half and half, but there were moments, especially at the beginning, where it was 90% women and women who live different realities to mine at home in some cases, who were going through really bad cases of domestic violence and whose lives were at risk. It was then that Saqib and I decided that the restaurant was going to be a feminist restaurant, and that we were going to focus on the well-being of the women in our team, specifically.

How do you use your work at Masala y Maíz to support the International Women’s Day March in Mexico City?

I want to name two groups I work with directly. The younger generations of women in Mexico are teaching me. There's one organization we work with for domestic violence education that is called Lentes Purpuras, and the other one is Restaurantera Feminista and they're really at the forefront of making change. They're creating a labor union. They're doing a lot of education for industry workers, and they are the ones who are kind of like telling me ‘No, Chef’ or ‘Yes, Chef, this is how we're doing things.’ We do the marches together. A few times, we've met at Masala y Maíz to draw the panels that we're gonna use at the march, and then all go together because it's also a big march, and it could be quite intimidating for some women. I go through like 80% of the march because it starts getting more crowded and I feel suffocated. But they go all the way in, and they're super organized. It is one of the largest Women's Marches in the world. It is incredible. Outside of the march, for three years the restaurant has become a safer haven because I can never guarantee safety 100%, especially because we're in Mexico. We try. So if you need water, if you need to use a bathroom, if you are an elder or a child, you can always knock on the door. That day we're closed. There's going to be people volunteering inside, and we'll be there in case somebody needs anything. I started with celebrations on the day of, and then I started wishing I was at the march. And I was like, if I wish I was there, I bet you my staff wishes they were, too. The pandemic made us more clear in our vision of how we support workers and the restaurant that we want to be. Coming back from that, we decided we were not going to open on the 8th.

The first time you go to the march, you are in shock and you will cry because you have never experienced anything like this. It's beautiful, it's powerful, it's gentle, and at the same time, it's strong. Through the years, I've brought different women, and we always have this moment of, you get chills, and you're walking through the main avenue in Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City, and the skies are full of purple dust, and women are chanting. It's electrifying, and it's like an awakening to be a part of it, even if you just decide to go three blocks. I didn't see the relevance until I lived it, and then I was like, wow, there's elders, there's kids, there's Indigenous women, there's the people who are fighting and are marching for all the women that are gone. It's really beautiful.

What did you decide a decolonized, feminist restaurant would look like in practice?

We're a labor rights restaurant, but one of the things that we do is we don't open at night. We have a lot of single mothers, and the reason is so families can be together, at least at night for a meal, to change the narrative that restaurant workers are martyrs, and that we work such long hours. We want to prove we can have a restaurant where people can have a life, where a woman can go home and be with her kids, or the younger women in my team who are single can go home safely. All of the leadership jobs are given to women and we give a lot of power to women in the restaurant. If we're doing an event that goes a little later at night, we hire private transportation to take them home. We have focused programs against domestic violence, and how to care for someone through a case of domestic violence, how to act, and give them tools and resources. Everybody has to take them. The industry has been run by men for the longest time, and there's a lot of oppression and silent oppression towards women. So we’ve fought it since the beginning. We do a lot of work with men too, in deconstructing patriarchy. And we do that actively–the way they communicate, the way they act, and it's not a restaurant for everyone. There are people who don't want to be a part of this program because they are not interested in deconstructing themselves. There is also a no-touch policy in the restaurant. In some countries, it might be obvious but you would be surprised when you're working in such close proximity. When we started Masala y Maíz, we had big hopes for a huge reach. We realized we would have a stronger reach by focusing on our immediate community, the restaurant, and how that would make an impact once they left.

If you look at the history of restaurants, most restaurateurs are always focused on the Eurocentric way of running a restaurant, also from the way tips are done. We always say customers are not always right. If you are not nice to our staff, you will have to leave the restaurant. We've kicked people out because they're inappropriate to women or men. Another thing we do is we use our physical paper menu to print slogans of different Global South fights and revolutionary movements aligned with our politics. We always credit everyone who has contributed to any of the recipes. This is something that doesn't happen usually in restaurants; even if a dish is created by a cook, it's the chef who takes the credit. We put the name of a person who created that dish on the menu–in a movie, you give credit. Or if you're writing an essay and you quote a book, you have to give credit. That's also very important in giving light to our team.

Given the violence against women we discussed, what is the relationship between hospitality and feminism in Mexico?

Most of my mentors in the U.S. were men. When I moved back to Mexico, I realized the ones who set the foundation for what the food industry is in Mexico City are women. There was a group of chefs in the ‘90s that cemented the big Mexican restaurants, that were giving light to our cuisine and doing this Mexican bistro-ish thing, but it was all always women. It was really incredible to come from a very male-dominated scene in the U.S. to a scene where I didn't feel like I needed to fight for my place as a chef. Once we were able to prove our concept, that we were a good restaurant, and that our food was delicious, there was no questioning of me being a woman or having authority in the kitchen. It was very beautiful and refreshing to see a lot of women chefs leading this industry.

To be honest, in Mexico everybody thinks there's machismo, and yes, there is. We have this reality also that we live as women with a lack of safety. I will never forget, I felt I was going to get kidnapped, and because of the privilege and resources I had, I was able to call an Uber and go into a store. Mexican Uber knows this reality, so I just made him drive around before he dropped me off at home, and then I called friends to follow me. There's all of this reality that is very different from what I lived before in the U.S., that's on the one side. But on the other side, there’s this immediate recognition. The only places where I felt I really had to fight for my place as a woman, where it's more of a systemic oppression, was in the U.S.

What is it like having to make that choice?

It doesn't feel great to have to fight for your place regardless. Here, it's crazy to feel unsafe and to live with this constant fear of watching over your shoulder. You get some things for others. I always had to fight, and I keep having to fight, especially white men in power. I am a fighter. I was raised in a matriarchy by women that are fighters, so I have a very strong voice and I've developed a stronger voice through the years. But not all women have the same privilege. I want to be an example in my industry but also give the tools to women I work with so they can learn how to have this voice as well.

Then last year, we were on Chef's Table, I was completely erased from my episode. I had to fight for them to put something of me in it. The whole thing is narrated by Saqib. They took out all of the feminist work we do at the restaurant, and they made it into a love story where I happen to fall in love with this highly politicized chef. That's a little mind blowing. A lot of young Mexican chefs who have different realities than me are gonna see that episode and are gonna see that love story of the man and the woman that falls in love with this man. I feel like chefs will miss such a good opportunity, and it makes me really upset because I have a responsibility for these women. They're just gonna see the show, and it's like, 'Oh yeah, it's a love story,' instead of having an opportunity to see a politicized female chef fighting for the rights of women in the industry. I had to fight. There's like five minutes of a 45 minute episode where you just tell Saqib's childhood story, where is mine? You have to put it in. They're like, okay, okay, but you know, they did a poor job. They did what sells, and I get it, but it's infuriating.

I'm always curious about food as metaphor, and not just as it presents in mestizaje, with a feminist lens on a menu. Can you talk about that?

I'm always trying to be so literal with my food and not so metaphorical. I do believe my food is very feminine and very gentle, and it balances. We use very strong flavors at Masala y Maíz, but we find balance in herbs and acid. If I would have to describe my feminism in a more metaphorical way, it would be that beauty. I studied art history, so I'm always looking at composition in the plates. I'm trying to be very direct and obvious so there's not a gray area in the consumption of a dish. For example, right now the most iconic dish at the restaurant is my shrimp with vanilla ghee and chile morita. That is a way to deconstruct and decolonize your palette and your taste. I'm being very intentional in telling the story of an ingredient and a culture where the Totonecs and the Olmecs used this combination of seafood and vanilla before me.

To me being this obvious is a way of giving credit to all the cultures and not taking to take like so much of the Global North does from our cultures, like the example of vanilla. This is an example of an ingredient that in Mexico was used in a savory manner, and then colonizers took it. Actually, the first suppressors to this culture were the Aztecs, and they were the first ones who first mixed it with cacao. And then the Europeans took them and made vanilla into a completely sweet thing. We think about vanilla, we think about white. How did that come about? In the dish, I’m stating the opposite to create a contrast. So when you eat this dish, it's spicy, but it fucks with your mind, because you smell the vanilla and you think pastry or a sweet, but it's not, and it makes you question everything you've ever believed about an ingredient. Here's the metaphor, though: I hope that the metaphor of this goes into the rest of your life and in how you question a belief system that you might never have questioned before.

A couple sleeping in their tentCanva

A couple sleeping in their tentCanva

Clinic are factoring more and more into health planning in the US.

Clinic are factoring more and more into health planning in the US.

Representative Image: Making pizzas for hungry people. Pexels I Photo by Jvxhn Visuals

Representative Image: Making pizzas for hungry people. Pexels I Photo by Jvxhn Visuals Representative Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Polina Tankilevitch

Representative Image Source: Pexels I Photo by Polina Tankilevitch Representative Image: Is there anything better than pepperoni? Pexels I Photo by Pixabay

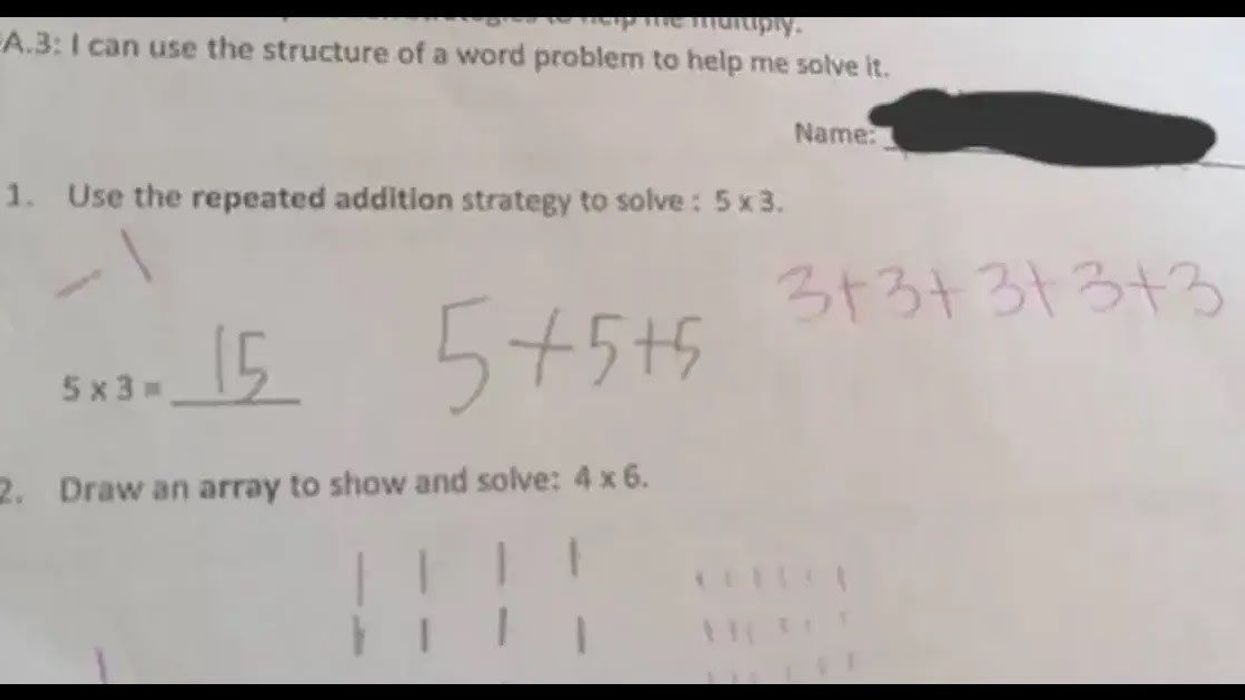

Representative Image: Is there anything better than pepperoni? Pexels I Photo by Pixabay "This story made my whole night better." Reddit I

"This story made my whole night better." Reddit I

Model Lauren Chan's 2025 Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue cover, photographed by Ben Watts. Ben Watts/Sports Illustrated,

Model Lauren Chan's 2025 Sports Illustrated Swimsuit issue cover, photographed by Ben Watts. Ben Watts/Sports Illustrated,

Fisherman at duskCanva

Fisherman at duskCanva Water rescue teamCanva

Water rescue teamCanva Pulling someone to safetyCanva

Pulling someone to safetyCanva You never know what you may catch in the waterCanva

You never know what you may catch in the waterCanva