Earth's abundance of water is what makes it a "blue planet." Scientists have long speculated about how all this water ended up here. Some studies suggested that water arrived on Earth through collisions with icy comets or asteroids. However, the question persisted: Did Earth's water come from outer space or from within? A 2014 study provided insight into this mystery when scientists discovered a massive reservoir of water trapped within hot mantle rocks. The findings were published in the journal Science.

The discovered reservoir contains three times the volume of all Earth's oceans combined. It was surprising, because usually, the Earth’s mantle, 254 to 410 miles deep, is an efflux of scorching hot rocks covered with magma. According to New Scientist, scientists have long believed that the mantle’s “transition zone,” the boundary between the upper and the lower mantle, could contain water trapped in rare minerals.

During this study, they finally discovered a colossal body of water trapped inside a blue rock called ringwoodite. Ringwoodite is a deep blue mineral, chemically similar to peridot, a green mineral often used in jewelry. “The ringwoodite is like a sponge, soaking up water,” Steven Jacobsen of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, said, per a university press release. “There is something very special about the crystal structure of ringwoodite that allows it to attract hydrogen and trap water. This mineral can contain a lot of water under conditions of the deep mantle.”

The team discovered this ringwoodite around 430 miles underground in the mantle. This gave a clue that the water on Earth could have simply seeped from within its core, rather than coming from a comet or asteroid collision. “It’s good evidence the Earth’s water came from within,” Jacobsen told New Scientist.

To conduct the research, scientists employed 2,000 seismometers that helped them study the seismic waves generated by more than 500 earthquakes. As these waves quiver through the Earth’s core, scientists can examine them from the surface. “They make the Earth ring like a bell for days afterward,” said Jacobsen. Since the waves take longer to travel through wet rocks than dry rocks, the speed of the waves told scientists which rocks could contain water. 434 miles deep, the temperatures and other conditions were just perfect to squeeze the water out of the ringwoodite. “It’s a rock with water along the boundaries between the grains, almost as if they’re sweating,” explained Jacobsen.

The discovery of this huge ocean could provide some fascinating insights about Earth’s water cycle, and how seas and oceans were initially formed on the planet. “We should be grateful for this deep reservoir,” said Jacobsen. “If it wasn’t there, it would be on the surface of the Earth, and mountaintops would be the only land poking out.”

“Geological processes on the Earth’s surface, such as earthquakes or erupting volcanoes, are an expression of what is going on inside the Earth, out of our sight,” added Jacobsen. “I think we are finally seeing evidence for a whole-Earth water cycle, which may help explain the vast amount of liquid water on the surface of our habitable planet. Scientists have been looking for this missing deep water for decades.”

This article originally appeared 4 months ago.

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes

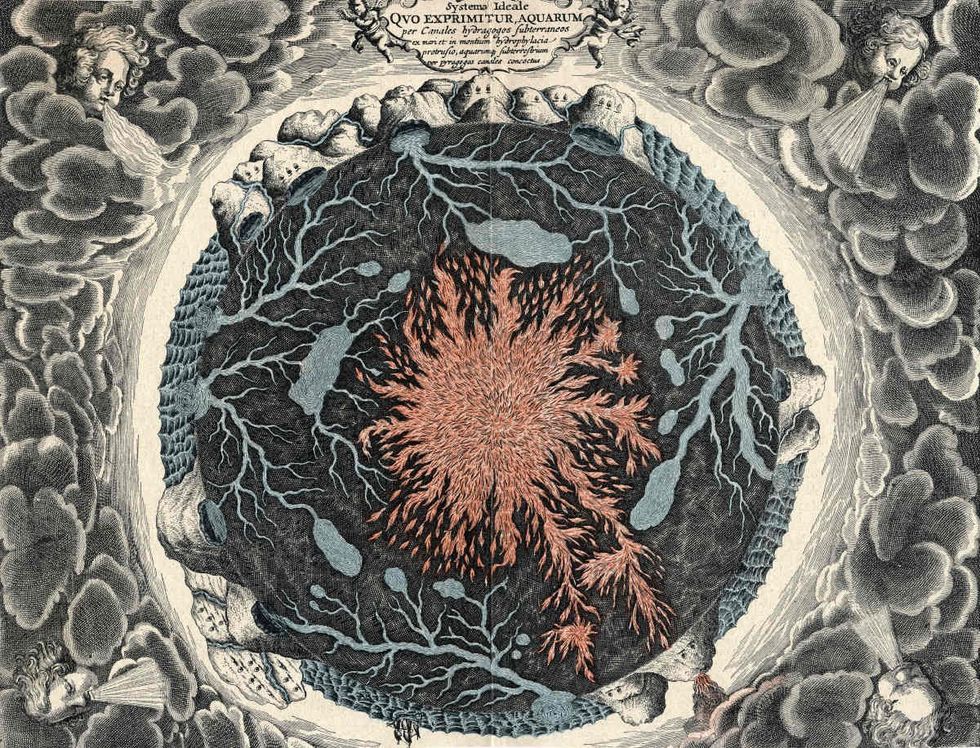

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images)

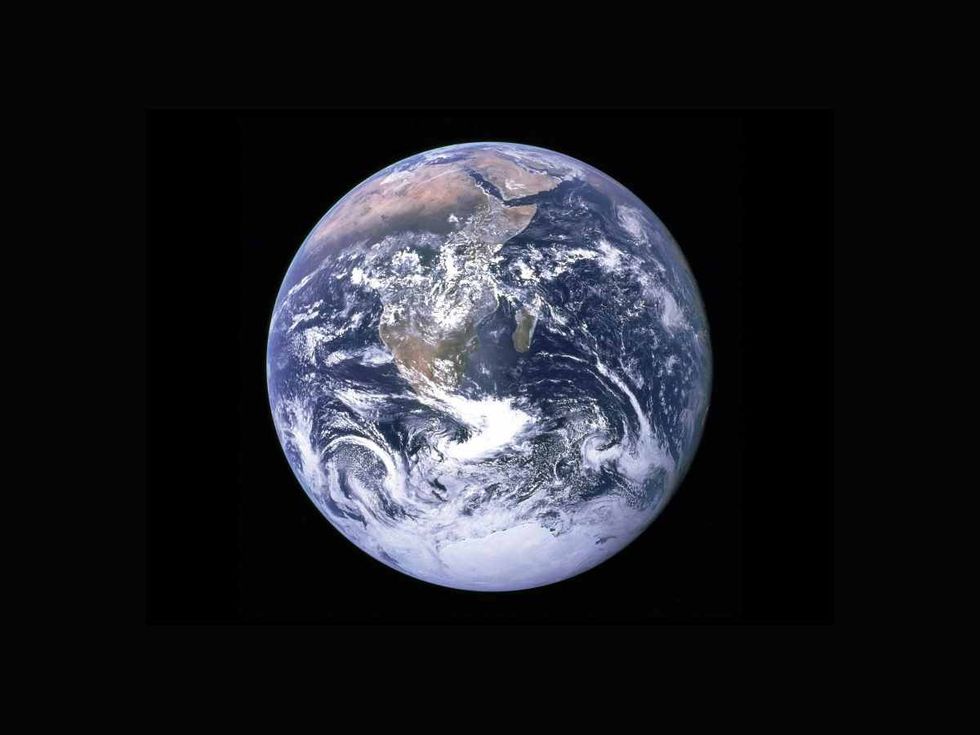

Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project

Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kellie Churchman

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Kellie Churchman Representative Image Source: Footprints of a long-neck dinosaur (Diplodocus), found in a quarry in Germany. (Photo by Alexander Koerner/Getty Images)

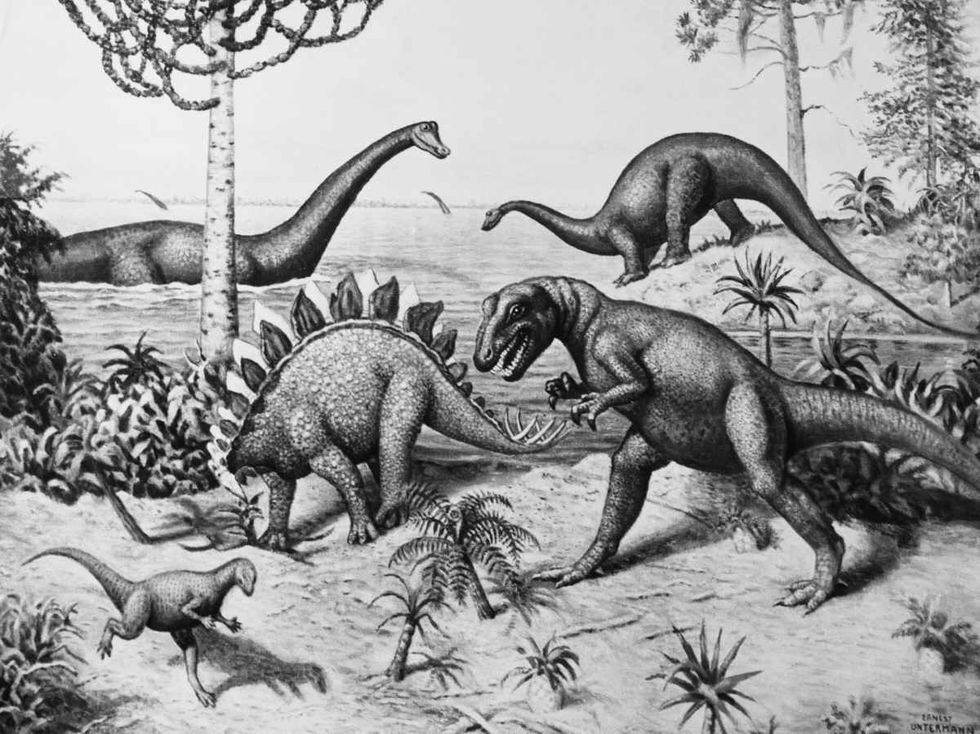

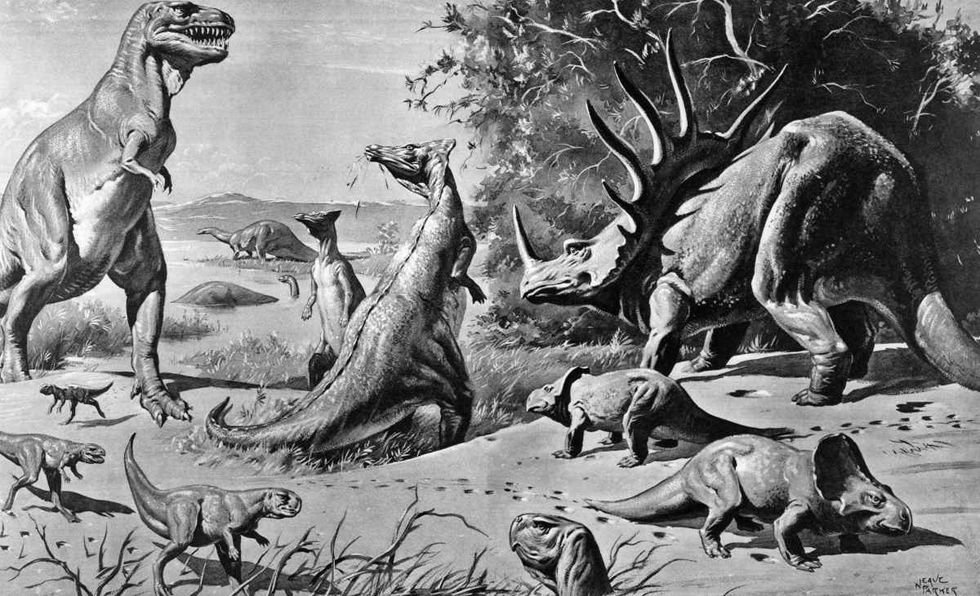

Representative Image Source: Footprints of a long-neck dinosaur (Diplodocus), found in a quarry in Germany. (Photo by Alexander Koerner/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Painting from a series by Ernest Untermann in the museum at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah.

Representative Image Source: Painting from a series by Ernest Untermann in the museum at Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. Representative Image Source: VARIOUS DINOSAURS IN GOBI DESERT. (Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: VARIOUS DINOSAURS IN GOBI DESERT. (Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images)

Large fire burning in the forest at night (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bianca Gruensberg)

Large fire burning in the forest at night (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | Bianca Gruensberg) Eternal Flame Falls in Shale Creek Preserve (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | WireStock)

Eternal Flame Falls in Shale Creek Preserve (Representative Image Source: Getty Images | WireStock) Comment by

Comment by

Representative Image Source: Aerial view of North Avenue Beach and Lake Michigan at Sunset, Chicago, Illinois, USA (Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Aerial view of North Avenue Beach and Lake Michigan at Sunset, Chicago, Illinois, USA (Getty Images) Representative Image Source: A scuba diver explores an old, wooden shipwreck in Lake Michigan. The waters of the Great Lakes are so cold that they preserve the many wrecks on bottom. (Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: A scuba diver explores an old, wooden shipwreck in Lake Michigan. The waters of the Great Lakes are so cold that they preserve the many wrecks on bottom. (Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Blue sand mountens (Getty Images)

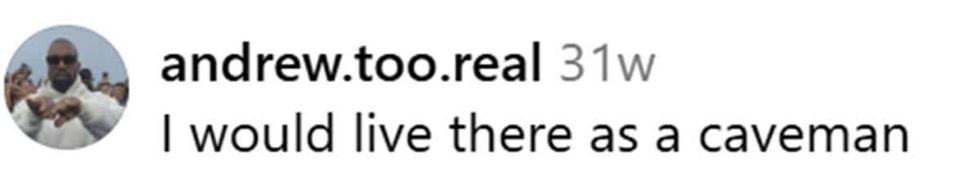

Representative Image Source: Blue sand mountens (Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Under water Ocean - Seabed With Sunbeam (Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Under water Ocean - Seabed With Sunbeam (Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Kokod Point, Ringgold Atolls, Pacific Ocean, Fiji Islands. (Getty Images)

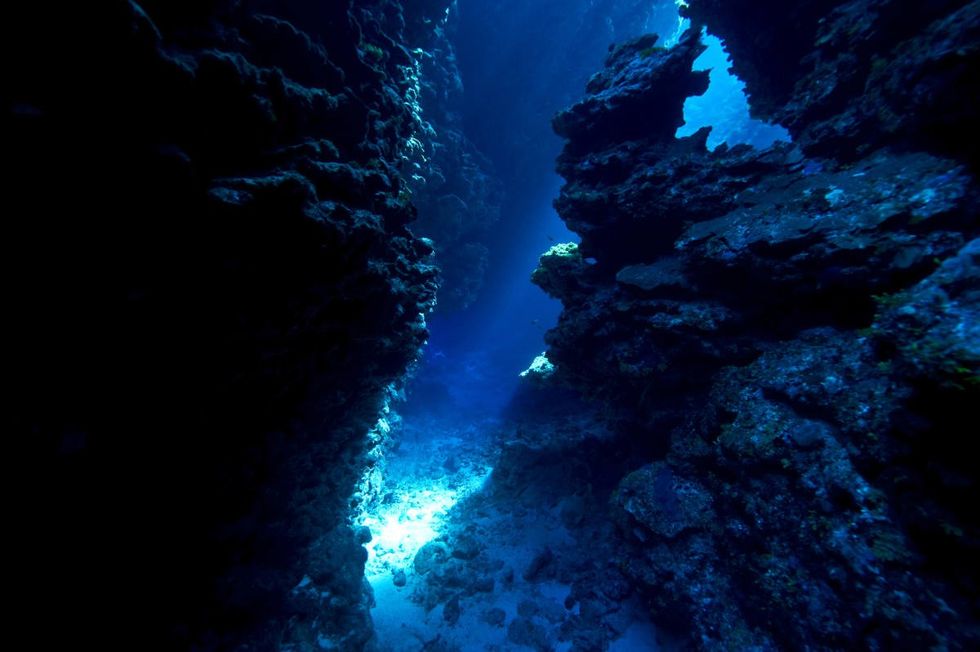

Representative Image Source: Kokod Point, Ringgold Atolls, Pacific Ocean, Fiji Islands. (Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Drone image looking down on a vortex of water in the Southern Ocean, Esperance, Western Australia, Australia (Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Drone image looking down on a vortex of water in the Southern Ocean, Esperance, Western Australia, Australia (Getty Images)

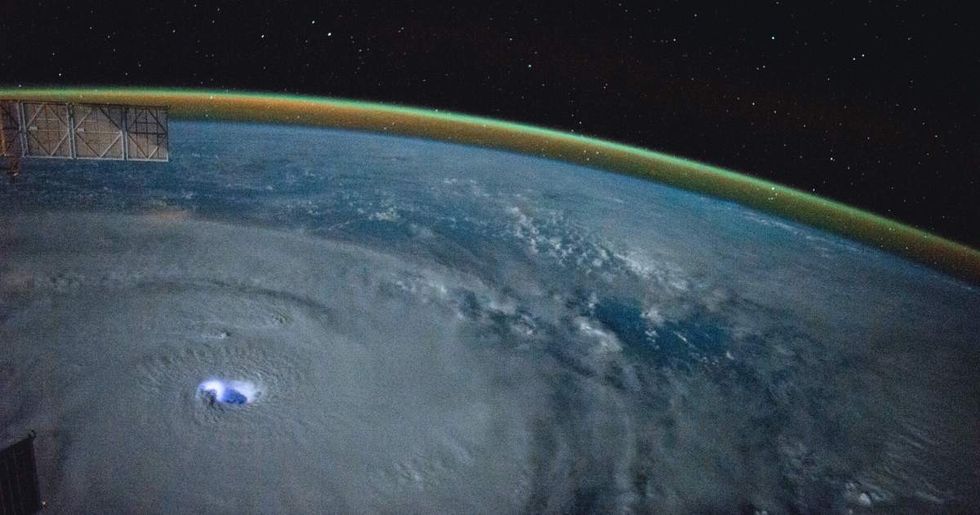

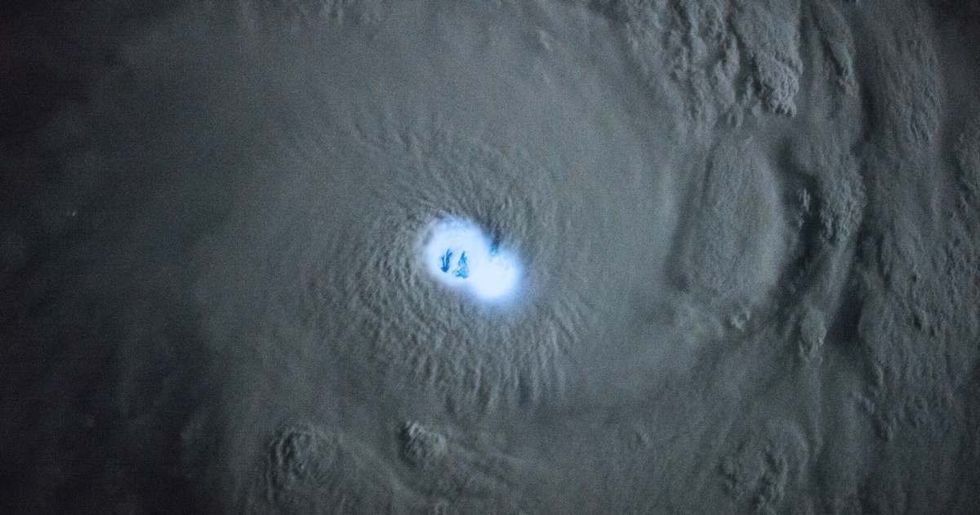

Representative Image Source: Super Typhoon, tropical storm, cyclone, hurricane, tornado, over ocean. Weather background. Elements of this image furnished by NASA. (Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Super Typhoon, tropical storm, cyclone, hurricane, tornado, over ocean. Weather background. Elements of this image furnished by NASA. (Getty Images) Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: