The Himalayas, one of the most majestic mountain ranges on Earth, rise so high that they make humans feel like mere dots. Beyond their breathtaking beauty, the Himalayas are crucial for geological studies. Recent research in 2023 suggests that the Indian tectonic plate, which forms the base of the Himalayas, may be splitting in two due to an unusual process.

The Great Himalayas Range, with its steep, jagged peaks, includes hundreds of mountains, the tallest being Mount Everest at 29,035 feet. About 40-50 million years ago, the Indian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate, causing the Earth's surface to buckle and form these towering structures. Because both plates had similar thickness, they clumped together instead of crashing, creating the colossal rocky formations we see today.

Stanford University geologist Simon L. Klemperer, along with his team of geodynamicists, traveled to Bhutan's Himalayan region to study helium levels in Tibetan springs. While the Himalayas are rich in elements like gold and silver, unusual helium levels suggested a potential dormant volcano beneath the surface.

The study considered two existing theories: the Indian Plate colliding horizontally with the Eurasian Plate, and the Indian Plate dipping beneath it, melting into magma and releasing helium. Klemperer's team found higher helium levels in southern Tibet compared to northern Tibet. This led to the conclusion that the Indian tectonic plate is splitting into two fragments beneath the Tibetan plateau, a process called "delamination."

Klemperer considered both theories and proposed a third theory, where he said that the processes mentioned in the first two were occurring simultaneously. While the top part of the Indian Plate was rubbing with the Eurasian Plate, the bottom part of the Indian Plate was diverging (subducting) into the mantle. The researchers originally presented their findings in December 2023 at the American Geophysical Union conference. “We didn’t know continents could behave this way and that is, for solid earth science, pretty fundamental,” Douwe van Hinsbergen, a geodynamicist from Utrecht University, told Science.

At #AGU2023 I showed results from Mediterranean orogens: @LamontsterTN1 and I identified a novel process of lithosphere unzipping: the crust split at the Moho from the subducting mantle lithosphere. And now @SimonKlemperer found exactly that in the Indian continent below Tibet!👇🏽 https://t.co/ZC5IEbwuWG

— Douwe van Hinsbergen (@vanHinsbergen) January 11, 2024

To carry out the study, Klemperer used a series of isotope instruments to measure helium bubbling in the mountain springs. They collected samples from about 200 springs across 621 miles and found the stark line where mantle rocks linked with the crust rocks. They discovered a group of three springs where the Indian Plate appeared to be peeling like the two yellow peels of a banana.

The layers of a tectonic plate are designed like a layered cake. The bottom-most layer is dense and thicker than the upper layers. But when two plates crash into each other, there is a possibility that the weaker layers may surrender and start to become fractured. So, before this research, scientists were aware that tectonic plates could peel away like this. But this process was mostly observed in the thick continental plates and simulated in computer models, “This is the first time that … it’s been caught in the act in a downgoing plate,” van Hinsbergen said.

This wobbling configuration of the tectonic plates pose a threat to the great mountain range, while also suggesting the danger of unexpected earthquakes and tremors. Though the study revealed precious data, the results depicted the contradictory forces of nature in dance with each other.

This article originally appeared 5 months ago.

A pair of scissors.

A pair of scissors. A can opener opening a tin can.

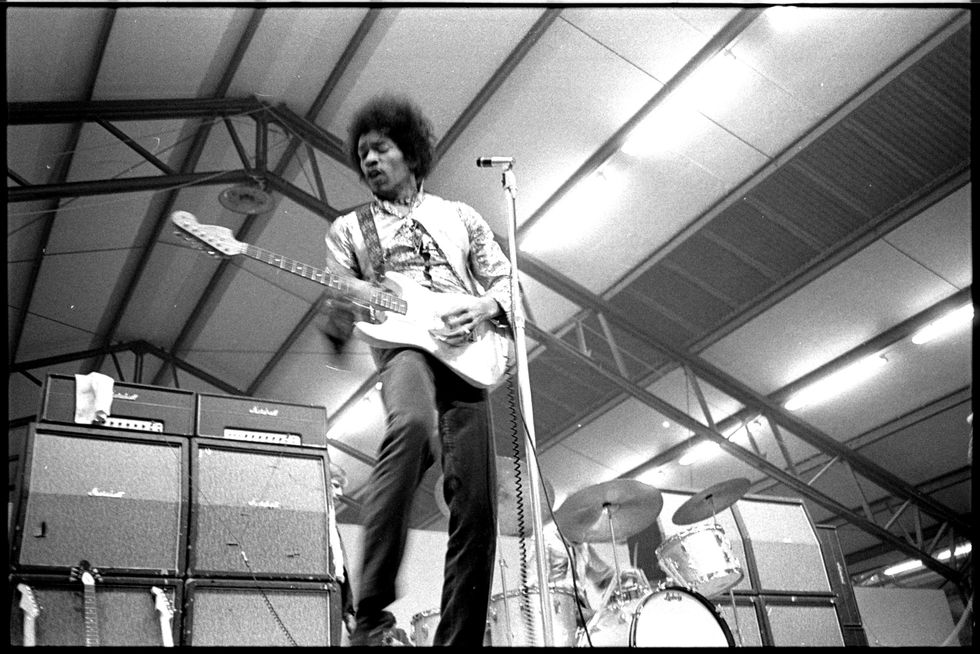

A can opener opening a tin can. Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain

Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain A man handing over $20 in cash.

A man handing over $20 in cash. A person using a power saw.

A person using a power saw.

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.