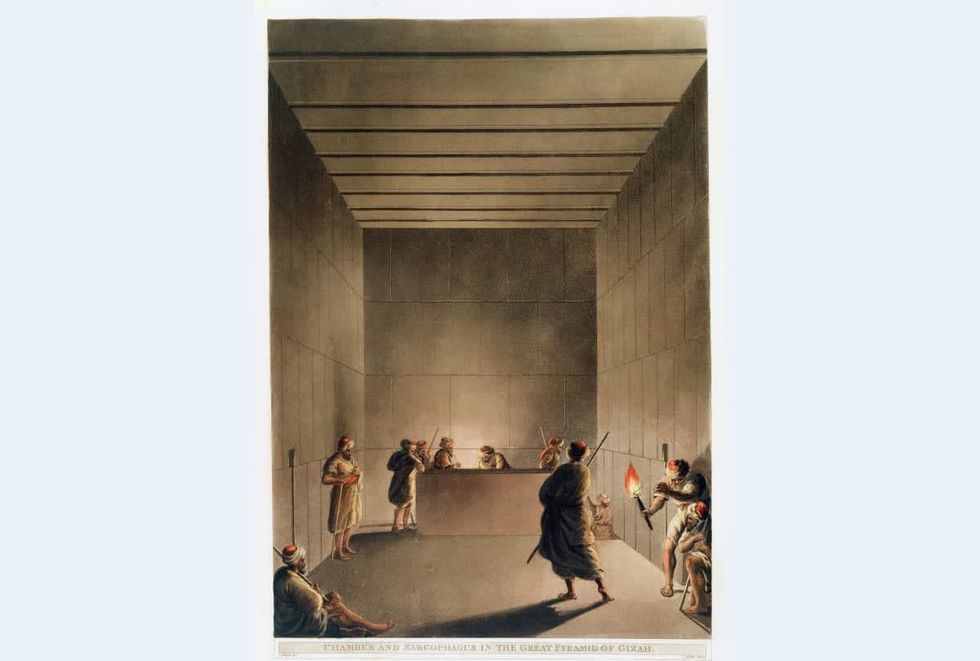

In 1872, explorer Waynman Dixon was surveying the Great Pyramids of Giza with permission from the Egyptian Antiquities Service. In the Queen’s Chamber, he found air shafts and, after drilling into them, discovered three Egyptian artifacts. These artifacts are the only objects ever found inside one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Located on the west bank of the Nile River, the 4500-year-old Giza Pyramid is the largest Egyptian pyramid and the tomb of Khufu, the second Pharaoh of the fourth Dynasty. However, it holds a mystery that has baffled archaeologists for decades. In 2017, scientists using muon tomography discovered a “big void” inside the pyramid, as reported by IFL Science.

Inside the pyramid, they found a massive void with empty chambers and halls, devoid of any precious artifacts or historical clues. Only the three artifacts have been discovered.

The three artifacts were a hook, a granite ball, and a short rod, which Dixon believed was made of cedar. Given the unusual nature of finding only these three objects, archaeologists proposed several theories about their origins.

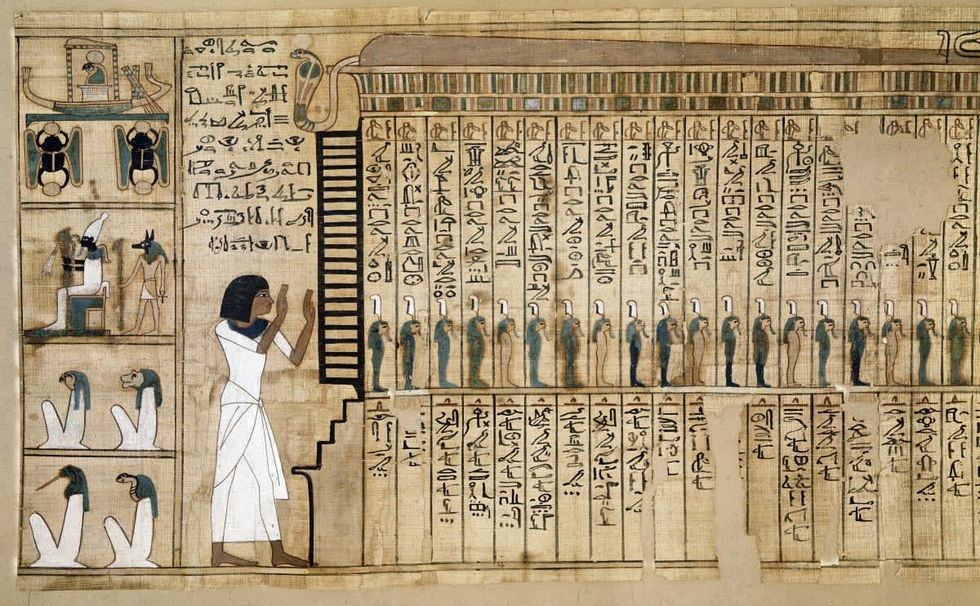

Dixon thought the artifacts were parts of a tool dropped by a worker. Some archaeologists believed they were part of a ritual by priests or architects. Others suggested the hook was used to open the deceased’s jaw so they could eat or drink in the afterlife, a concept central to Egyptian beliefs where pharaohs were expected to become gods.

Dixon kept the ball and hook while his friend James Grant took the piece of cedar wood. After Grant's death in 1895, his daughter donated the cedar to the University of Aberdeen in 1946, per CNN. The artifacts were almost lost for over a century until they were received by the British Museum in 1972. However, the wooden rod remained missing until a curatorial assistant at the University of Aberdeen made a "chance discovery" in 2019.

Abeer Eladany, originally from Egypt, was sorting through the university’s Asia archives when she came across a cigar box marked with her country’s former flag. Inside the tiny tin box, she found a set of semi-thick wooden splinters. Eladany had worked at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo for over a decade. She instantly started flipping through the museum’s records and learned that she had chanced upon the lost artifact from the Pyramid of Giza.

“Once I looked into the numbers in our Egypt records, I instantly knew what it was, and that it had effectively been hidden in plain sight in the wrong collection,” she said. “I’m an archaeologist and have worked on digs in Egypt but I never imagined it would be here in north-east Scotland that I’d find something so important to the heritage of my own country.”

“It may be just a small fragment of wood, which is now in several pieces, but it is hugely significant given that it is one of only three items ever to be recovered from inside the Great Pyramid,” Eladany added. “The University’s collections are vast – running to hundreds of thousands of items – so looking for it has been like finding a needle in a haystack. I couldn’t believe it when I realized what was inside this innocuous-looking cigar tin.”

The wood was processed through radioactive carbon dating, which dates it between 3341 and 3094 B.C., nearly 500 years before Pharaoh Khufu’s reign. Scientists believe these cedarwood fragments may have come from a larger wooden block.

“It is even older than we had imagined. This may be because the date relates to the age of the wood, maybe from the center of a long-lived tree. Alternatively, it could be because of the rarity of trees in ancient Egypt, which meant that wood was scarce, treasured, and recycled or cared for over many years,” explained Neil Curtis, head of museums and special collections at the university.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on May 24, 2024. It has since been updated.

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia

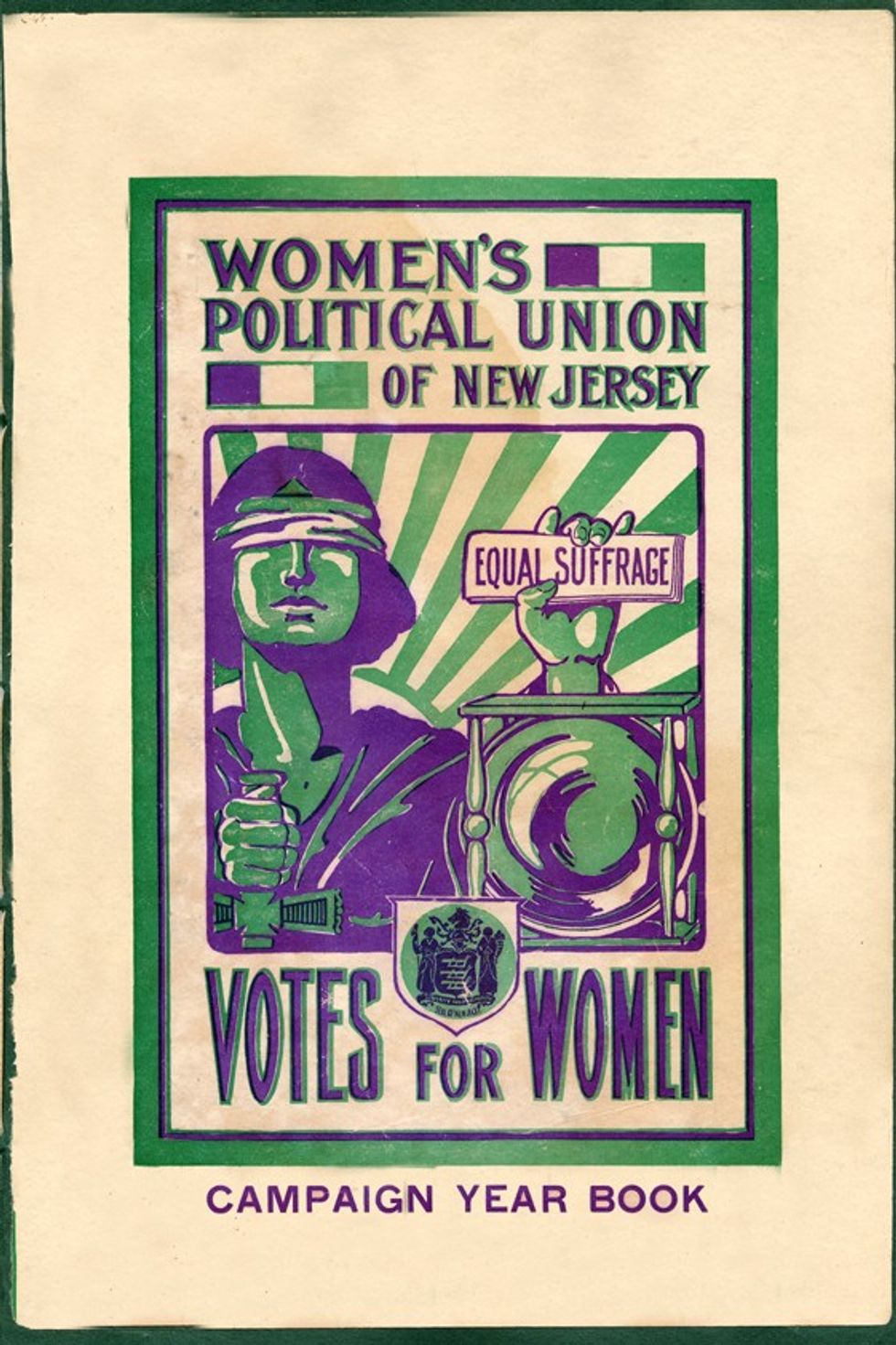

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: