On the western edge of the Monte Albo mountains in Sardinia, Italy stands the comune, the municipality, of Lula. Twice a year, on May 1 and October 4, groups of people make the pilgrimage to Lula on foot from Nuoro, some 40 miles away for the Feast of San Francesco. Upon their arrival, they’re rewarded with a recipe some 300 years old: Su filindeu, or tears of god, a pasta so difficult to make there are now only a handful of people in the world who can do it.

The pasta is served in a lamb broth made with generous portions of pecorino primo sale, a cheese made of sheep’s milk. While the recipe has traditionally been passed down matrilineally, masters of the delicacy like Paola Abraini--who lives in Nuoro, where the sacred recipe is also from--have started to instruct others. According to Atlas Obscura, “Abraini, who is currently in her mid-sixties, made a conscious decision to teach people outside of her family to make it, in large part because not everyone had a daughter to inherit the knowledge.”

One of those people, the site shares, is the chef Rob Gentile, who went to Sardinia to learn from Paola herself: “There are a number of people in Italy saying, ‘You know what? Anyone can learn how to make it. Why would we let this go extinct?’,” Gentile told them. Su filindeu now appears on the menu at Gentile’s Los Angeles restaurant Stella and on the menu of chef Lee Yum Hwa’s Singapore restaurant Ben Fatto 45. Another restaurant in Nuoro, Il Rifugio, also serves the pasta.

What makes su filindeu so difficult is partly the process of making the pasta itself–one thick rope of semolina pasta dough is turned and pulled eight times to produce 256 thin, almost fringe-like strands. The strands are then placed on a large disc in three layers–but the pasta can never get too dry or the layers won’t stick to each other. This large disc of pasta is then dried in the sun–in the fall, it can take up to three days. The disc is then broken into delicate shards and added to the homemade lamb broth with cheese. The other difficulty is in making the dough. Semolina can both absorb and release a lot of water, so the amounts have to be just right and account for local heat and humidity. The dough has to be extremely soft and elastic, and the only way to tell if it’s ready is really with enough experience of making it. Many have tried and failed–famously among them is lauded British chef Jaime Oliver. Similarly, Barilla pasta hoped to make a machine that could handle the process, and they too could not succeed.

Because masters like Abraini continue to pass on the recipe to others, there becomes a hope that su filindeu as a recipe will survive. While some have come through and found it too difficult, others carry on. Food archive The Ark of Taste, created by the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, currently lists su filindeu as an endangered recipe. Recipes like su filindeu are important because they teach us about a location’s heritage and history. As Saveur wrote when covering the dish, “What we don't eat vanishes.”So many recipes like this have been lost already, but if there’s the opportunity to preserve it–again, why not? Not everything should be fast food, especially when slow food carries so much culture and history withit. Paola and people like her end up preserving not just a dish, but a legacy.

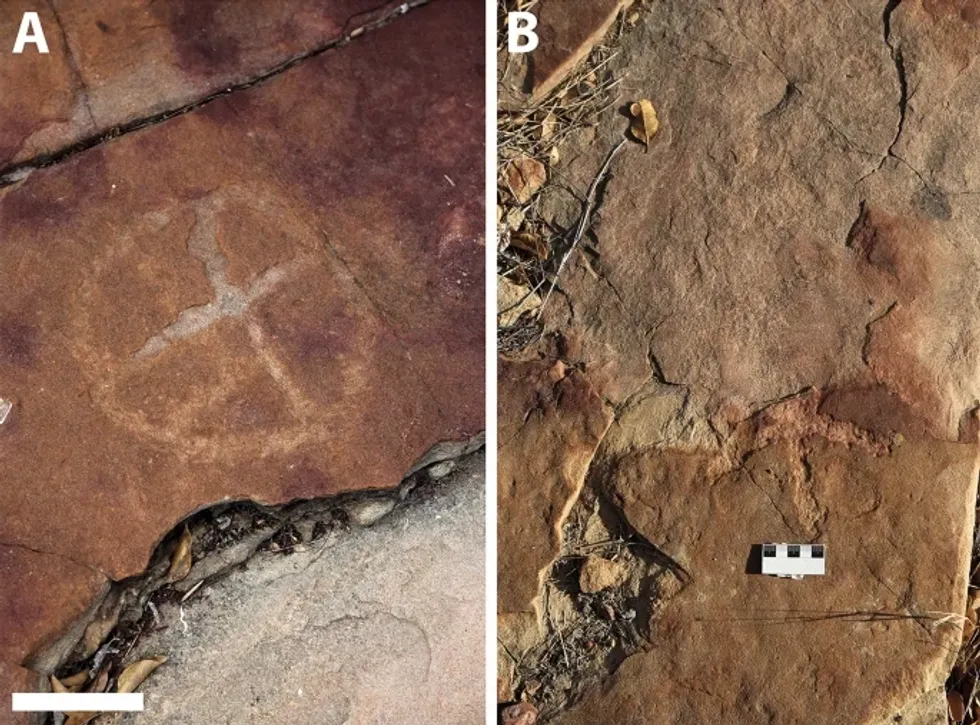

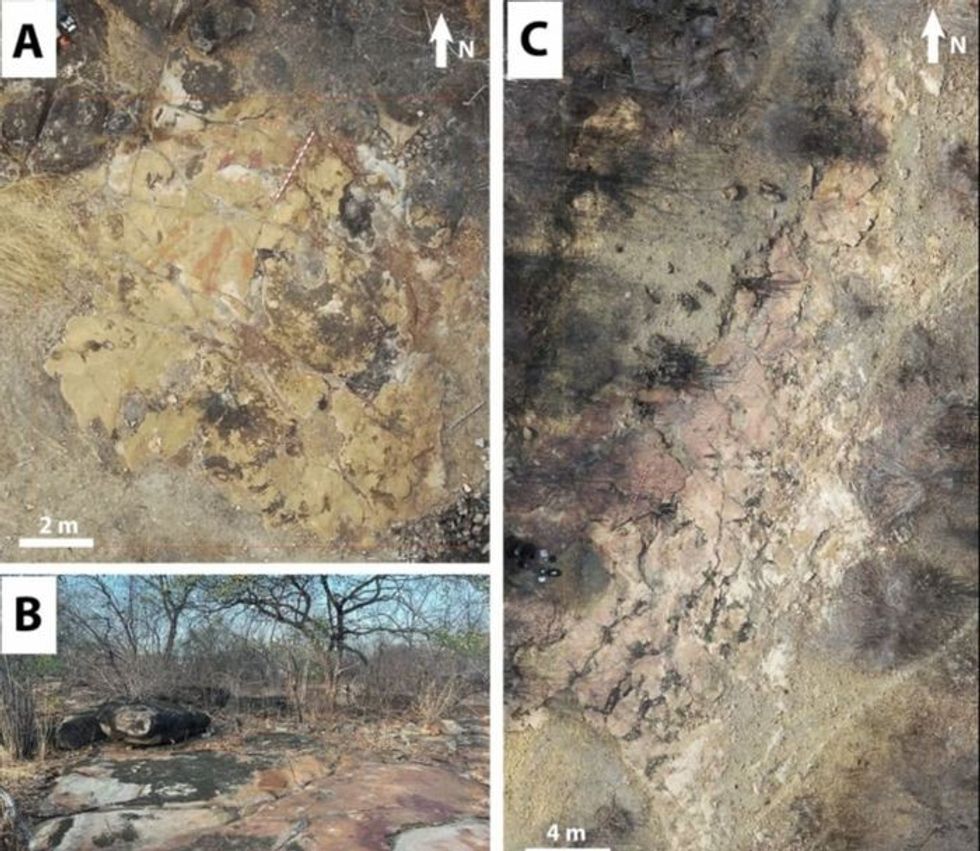

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper

Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

It's a beautiful day outside Wrigley Field. | It's a beautif… | Flickr

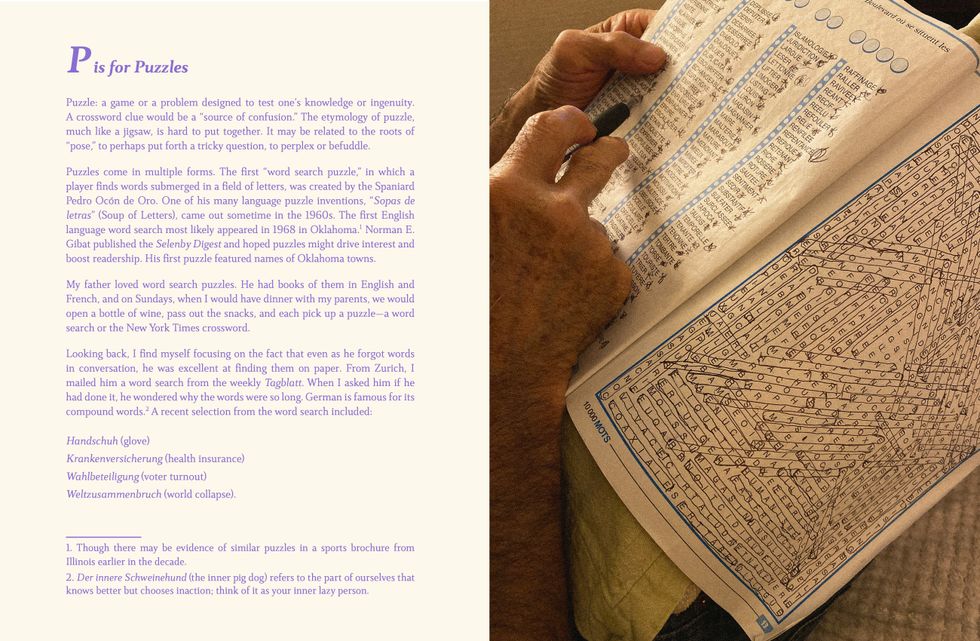

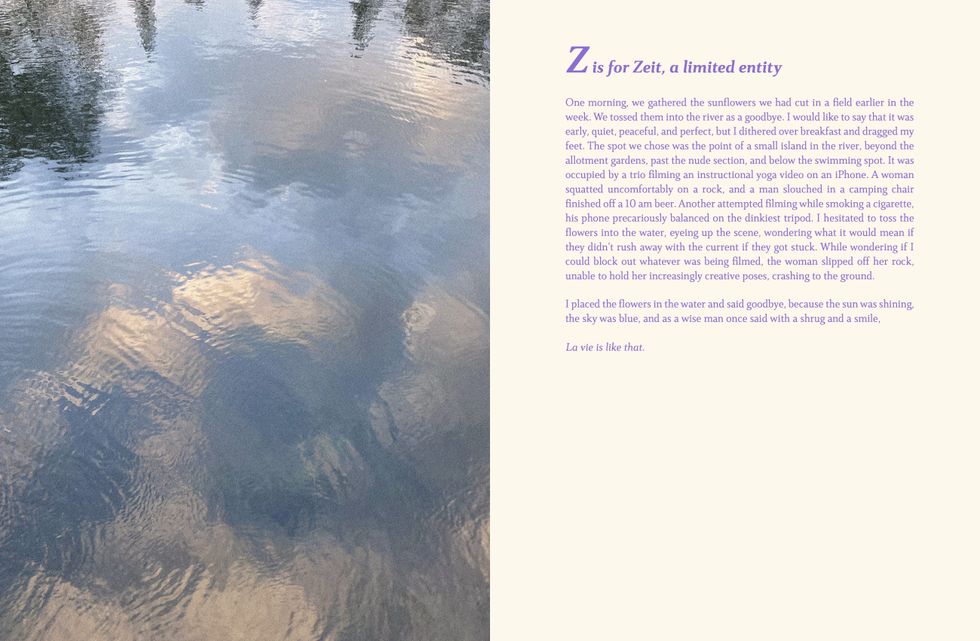

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant

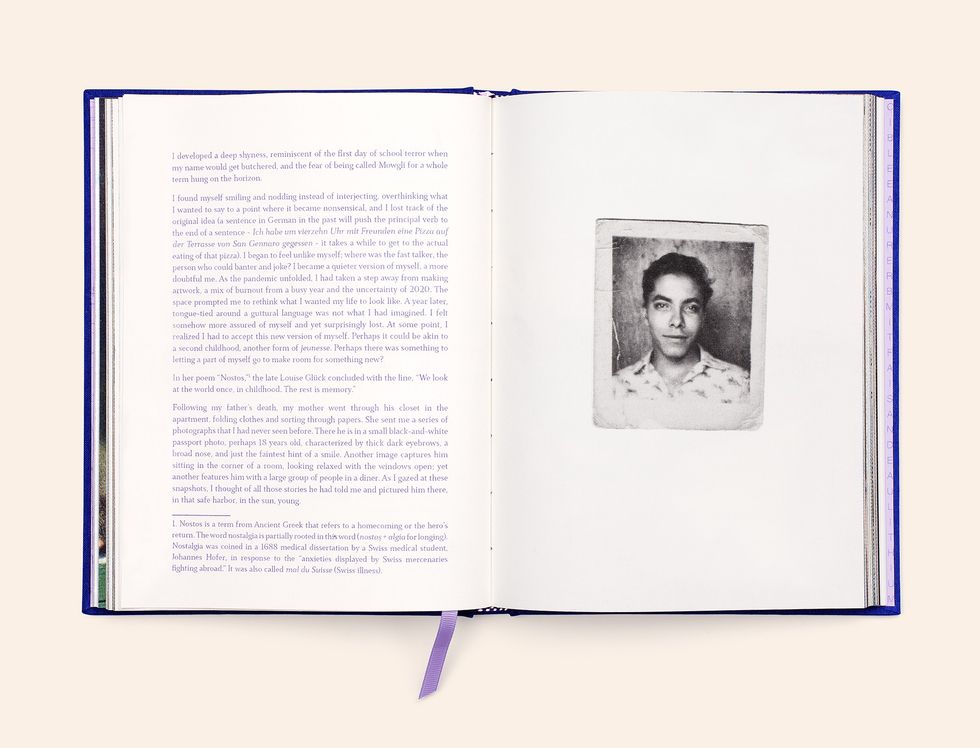

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like thatMagali Duzant Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

Selection from Magali Duzant's La vie is like that featuring her father, Jean Gérard Benoît Duzant, as a young man.Magali Duzant

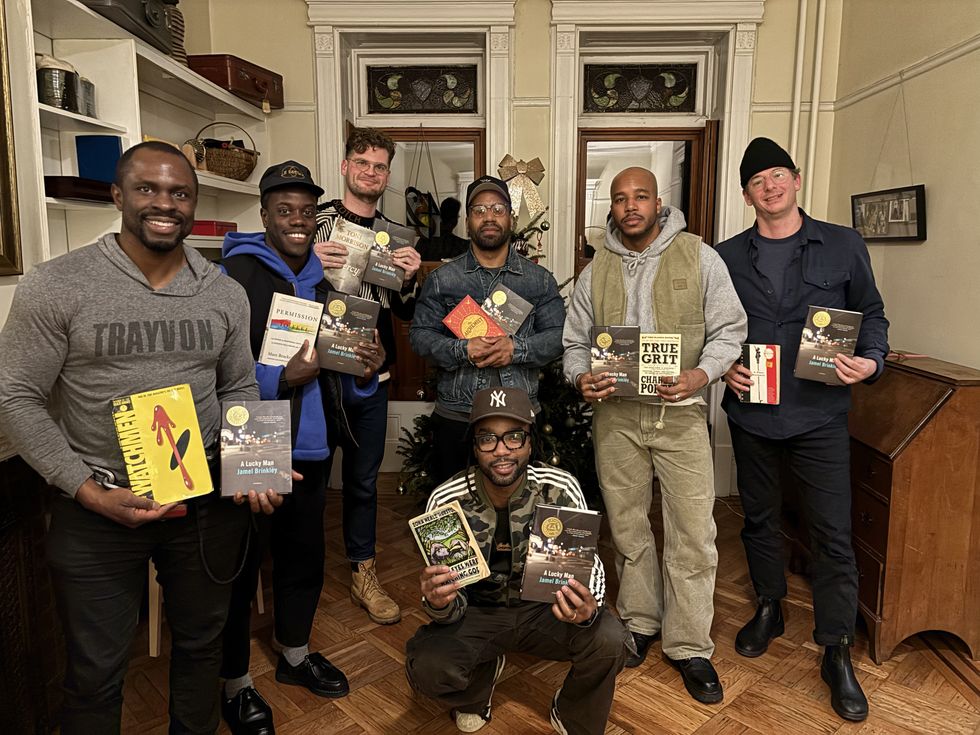

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel

Books at the first meeting of the Fiction Revival book clubYahdon Israel Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the first Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel

Attendees at the second Fiction Revival meeting.Yahdon Israel