“We would work for months at a time, and we would just sit on the floor of the storage room opening up bags and boxes,” said Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez, co-curator of the new exhibition “dearly Loved friends:” Photographs by Sheyla Baykal, 1965-1990 featuring the work of photographer Sheyla Baykal.

Baykal passed away in 1997 from cervical cancer, but had been photographing the downtown avant-garde performance art scenes in New York City for over 30 years. When she learned she had terminal cancer, she willed her archive to her friend, the performance artist Penny Arcade. For decades, Arcade had been trying to get people to consider Baykal’s work, which documented with love one of the last great bohemian eras in New York. There were fits and starts. A review of a 2000 group show featuring Baykal’s work in The New York Times shared that “her work deserves to be better known,” but until now it mostly hasn’t been.

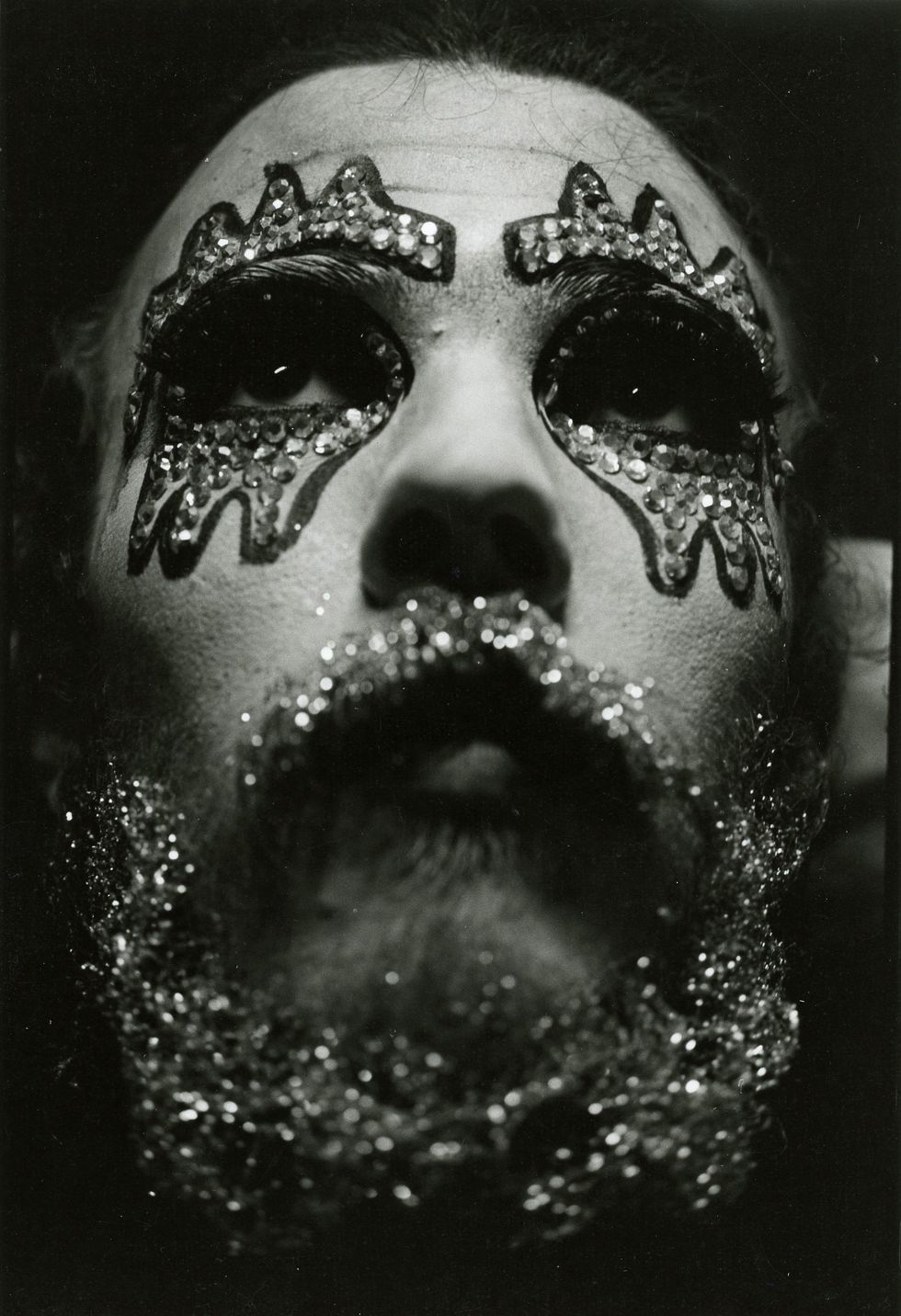

“dearly Loved friends,” curated by Yáñez with Penny Arcade, features Baykal’s photographs of New York artistic and literary stars like Frank O’Hara, Willem de Kooning, Candy Darling, and countless others. It is the first solo exhibition of Baykal’s work since 1993 and her fourth solo show ever, despite a lifetime dedicated to the people in its images. “Sheyla should have always [been] among the most famous because she had such an incredible background,” Arcade said.

Indeed, Baykal did lead a fascinating life, having run away from her native Canada at 18 only to immediately join the New York art world of 1962. A family friend was in the same circles as the artists, playwrights, and poets that comprised the city’s downtown scene at the time, and Baykal soon entered the fray. In fact, she even appears in two Alex Katz paintings from the time. To make extra money, lauded photographer and friend Peter Hujar suggested she become a model, and in 1964 she joined the famed Ford Modeling Agency, now Ford Models. While at Ford, she posed for outstanding photographers like Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, and Hiro. Shots from her modeling portfolio even appear in the exhibition. Baykal’s personal relationship to a life behind the lens, however, began in 1965 when she purchased her own camera, a Nikon F. “She's that real model who went behind the camera, you know,” Arcade says. “So there's a real human interest story there, besides the fact that she was outrageously beautiful and the fact that she was part of a coterie of artists…she was really in the center of hugely creative circles that were culture-defining.”

Baykal continued to expand her practice for the next several years, whether she was documenting drag balls or protests or photographing on the Hippie Trail between Europe and Asia or producing emotional portraits. Her images were published in the influential Newspaper, “a wordless, picture-only periodical thatran for fourteen issues and featured the disparate practices of over forty artists,” which was co-edited by Hujar and later hung in the Museum of Modern Art.

Baykal also performed with the legendary performance art troupe The Angels of Light, known for their commitments to gender-and-genre-bending, glittery revelry on stage. This became another of the worlds Baykal inhabited downtown, and beginning in 1974 she produced and directed the now-historic Palm Casino Revue shows, which brought together performers and nightlife denizens of all stripes. As its former lighting designer Steve Turtell described it, “Take a big slice of vaudeville, top with a hefty dollop of musical comedy, add in some thrift-shop, nineteen-thirties Hollywood glamour, season it with early punk rock and the nascent, Lower-East-Side art scene…and you’ll get some idea of the wild ride that the Palm Casino Revue gave to its lucky audiences.” The show ended, however, when Baykal faced non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and lived quietly for two years in Oakleyville on Fire Island with the artists Paul Thek, Robert Wilson, and Peter Hujar.

Yáñez learned about Baykal briefly in 2015, but it was with Newspaper, on which Yáñez wrote his 2018 undergraduate thesis that he then adapted into a 2023 book, that he met Arcade, licensing Baykal’s work for publication. Later, Yáñez had been researching Paul Thek, and hoped to find more information about work the artist made on Fire Island. Yáñez contacted Arcade to see if there might be anything amongst Sheyla’s belongings in storage.

Arcade’s storage room had moved a number of times and all the boxes had shifted. “I had the patience and the interest to sit down with Penny and go through everything and start to categorize and separate,” Yáñez said. “I just was in awe at the sheer amount of work, and I have never seen any of it outside of what was published in Newspaper,” Yáñez continued. “I think that's also why the exhibition is such a big deal. Nobody has seen this work and it's really good, and there's so much of it.” The process took about two years, and he connected Arcade to the organization Soft Network, where the exhibition takes place, to move forward.

Soft Network “preserves and provides access to the work of vital yet often vulnerable experimental artists and those who care for them.” When an artist passes away, they leave behind work like canvases or photographs or sculptures, and that work needs to find a home lest it be abandoned, stuck in storage, or worse. Soft Network helps artists and people who’ve been left artist estates to catalog and care for the work that remains, creating potential for its life moving forward, be it in a museum, a gallery, or another archive. One of the ways they do this is through their Archive-in-Residence program, which lasts for two years. Baykal is the current Archive-in-Residence and her work arrived at Soft Network six months ago; there were about 25-30 Bankers Boxes of material. During the residence, her work will be “accessible through cataloging, digitization, research, programs, and exhibitions,” and Marina Ruiz-Molina, a conservator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will counsel on steps for preservation, the organization shares.

Soft Network Executive Director Chelsea Spengemann says the goals for Baykal’s archive include constructing a timeline of her life, introducing her work to people, organizing contact sheets and negatives, digitizing slides, developing a database of her work, and developing a best-practice system to print the works as Baykal wished. There will be another show next year as all of these processes continue.

Yet the question of why Baykal’s work stood unrecognized for so long still stands. “It's connected to the lack of a market, mostly, but she just wasn't operating in that system,” Spengemann says. “Sheyla and her community, and what's so appealing about them, is that they were surviving and thriving outside of any art market or commercial market.” The appetite for photography like Baykal’s in the 80s and 90s was also not what it is now, Spengemann says, plus Baykal said she did not have money to make prints for an artist portfolio and bring it to galleries. After her passing, Baykal’s archive also didn’t have a foundation or structure behind it previously besides Arcade, the way some artists do; a huge reason an organization like Soft Network exists is because managing and maintaining an artist’s archive is a tremendous undertaking for anyone.

Baykal made prints for some time, but as she ran out of money, she stopped printing formal photographs and instead began using “laminated color Xerox and laser prints as well as slide shows as a means of exhibition,” Soft Network writes. The work she ended up making through the 1980s became a testament to the friends she made in the downtown scene, many of whom lost their lives to AIDS. Her work became as much a love letter as a document. “She documented a group of people who are no longer here, who died largely because of government neglect and during the AIDS crisis, and it was a huge loss of life, and it's a lot of people whose stories have not been told,” Yáñez says, adding that one of the goals of Baykal’s Archive-in-Residence is to identify artists in the images and prepare biographies of them. “[Baykal] was at her core a portraitist, and so the stories of the people in the photographs do matter. And I think that was very important to her.”

“dearly Loved friends” consists of portraits and documentary images, slideshows and ephemera; the latter includes an installation Yáñez made of funeral programs and obituaries Baykal kept as her friends passed on. In this way, the show chronicles Baykal’s life as well as those of her friends, who wind through her images. These were people who lived vibrantly and creatively in a New York where they could do that; they knew what it meant to have an artistic, alternative life in another time. “We live in a culture where more and more the existence of the alternative is erased…I think when people see Sheyla's work, see Sheyla, they'll be inspired into their own individuality and authenticity, because she was this hugely authentic, creative being who was completely committed to her community,” Arcade says. “If you want a quick route into Bohemia 101, Sheyla is one portal.”

Visualization of a black holeImage via Canva

Visualization of a black holeImage via Canva

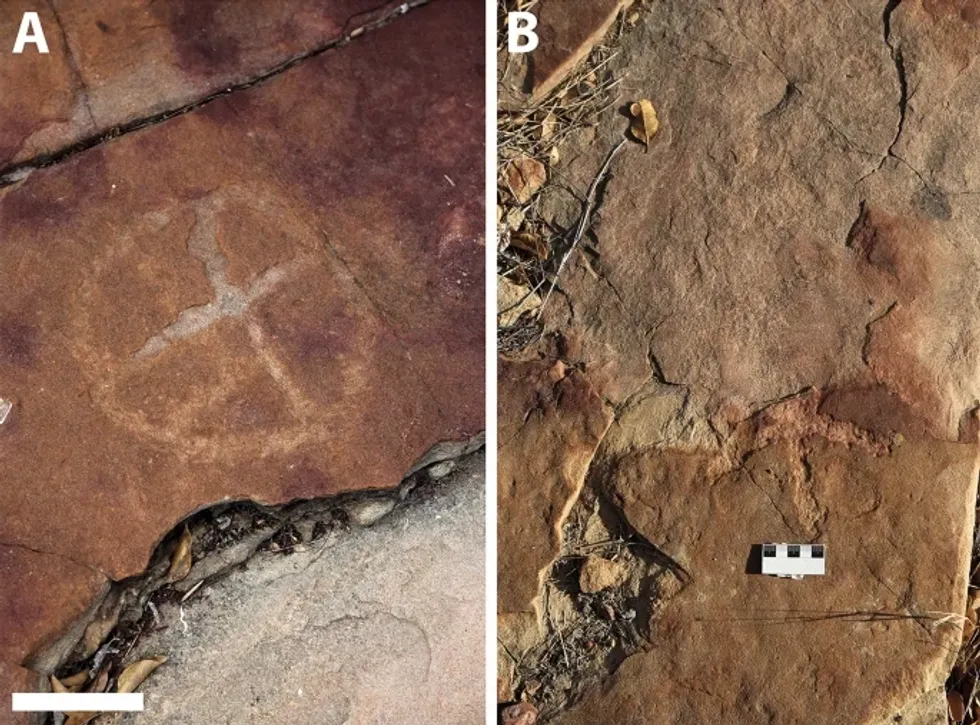

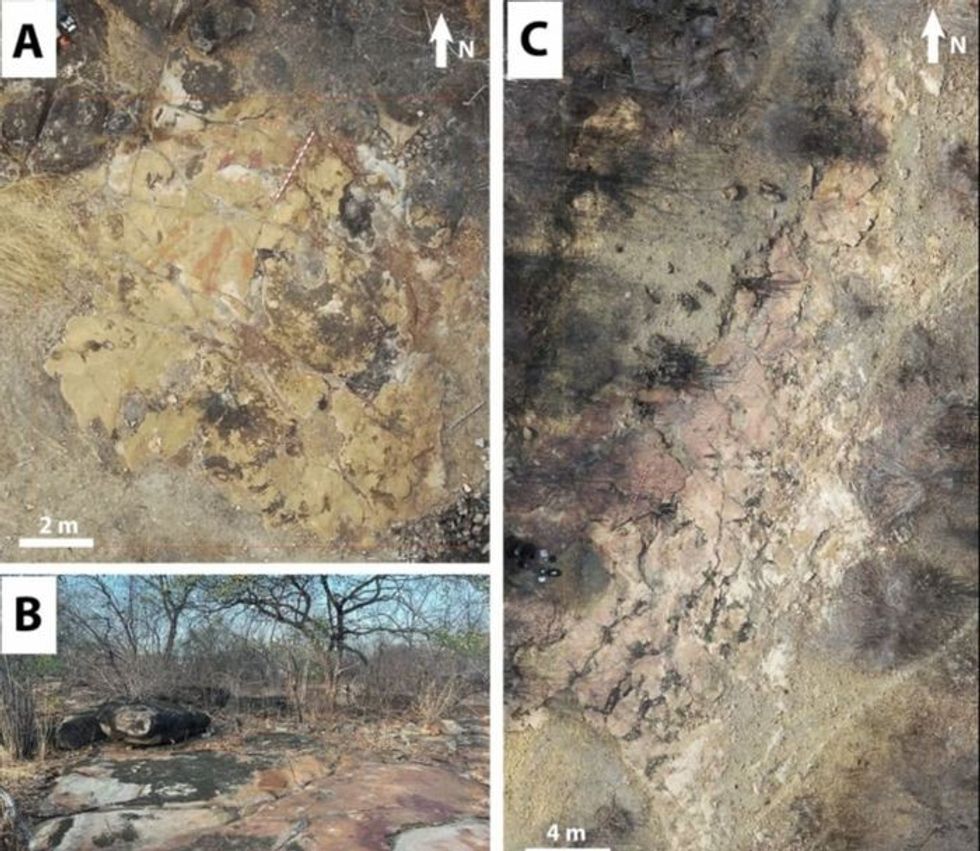

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper

The contestants and hosts of Draggieland 2025Faith Cooper Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper

Dulce Gabbana performs at Draggieland 2025.Faith Cooper Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper

Melaka Mystika, guest host of Texas A&M's Draggieland, entertains the crowd

Faith Cooper