Around 200 million years back, a supercontinent called Pangaea that accounted of the entire landmass on Earth, split into different continents that drifted apart with time. The movement of tectonic plates often results in cracks on Earth's landmass and is now threatening to split the second-largest contient Africa into two parts. The crack was observed in the East African Rift System (EARS), according to Live Science.

According to BBC Science Focus, the crack was first noticed in March 2018, when the ground tore itself apart in southwestern Kenya. Filled with volcanic ash, the tear remained undetected for several years until the region experienced heavy rainfall and water gushing through it squeezed out the layer of ash. Following this the massive crack swallowed up a portion of the Nairobi highway.

Currently, the colossal crack appears in the EARS, a network of valleys that's about 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) long, from the Red Sea to Mozambique. Geologists believe that this crack is rupturing the African plate into two separate parts, the larger Nubian plate and the smaller Somali plate. Live Science explains that the Somali plate is pulling eastward from the Nubian plate. Additionally, both of these plates are also breaking apart from the Arabian plate in the north, creating a V-shaped rift system in the Afar region of Ethiopia.

“The East African Rift started forming about 35 million years ago between Arabia and the Horn of Africa in the eastern part of the continent,” Cynthia Ebinger, chair of geology at Tulane University in New Orleans, told Live Science. About 25 million years ago, this rift started stretching southward and pulling apart northern Kenya.

The cause behind the crack, according to BBC, was “huge volcanic eruptions called flood basalts – which send lava gushing from emerging fissures like flood waters – and fractured the brittle continental crust into a series of faults.” Another reason could be soil erosion, as Lucía Pérez Díaz from the Royal Holloway University of London wrote in The Conversation. She explained that geologists think that this crack is an erosional gully, although questions remain about its formation in the specific location. They are trying to find out of its appearance has anything to do with the East African Rift. The crack could be the result of the erosion of soft soils into gap caused by the rift.

But is it alarming that Africa, the second-largest continent, may split apart? If Africa is ripped apart, there are different ways in which that might happen. One scenario has most of the Somalian plate separating from the rest of the African continent, with a sea forming between them. This new landmass would include Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and the eastern parts of Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique, Ebinger said. So, Africa is indeed splitting into two continents, but, as Ebinger noted, the process may take another million to 5 million years. "The rifting right now is very slow, about the rate that one's toenails grow," Ken Macdonald, a distinguished professor emeritus of Earth science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, told Live Science.

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anni Roenkae

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Anni Roenkae Representative Image Source: Pexels | Its MSVR

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Its MSVR Representative Image Source: Pexels | Lucian Photography

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Lucian Photography

Representative Image Source: Pexels | francesco ungaro

Representative Image Source: Pexels | francesco ungaro Representative Image Source: Pexels | parfait fongang

Representative Image Source: Pexels | parfait fongang Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |  Image Source: YouTube |

Image Source: YouTube |

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes

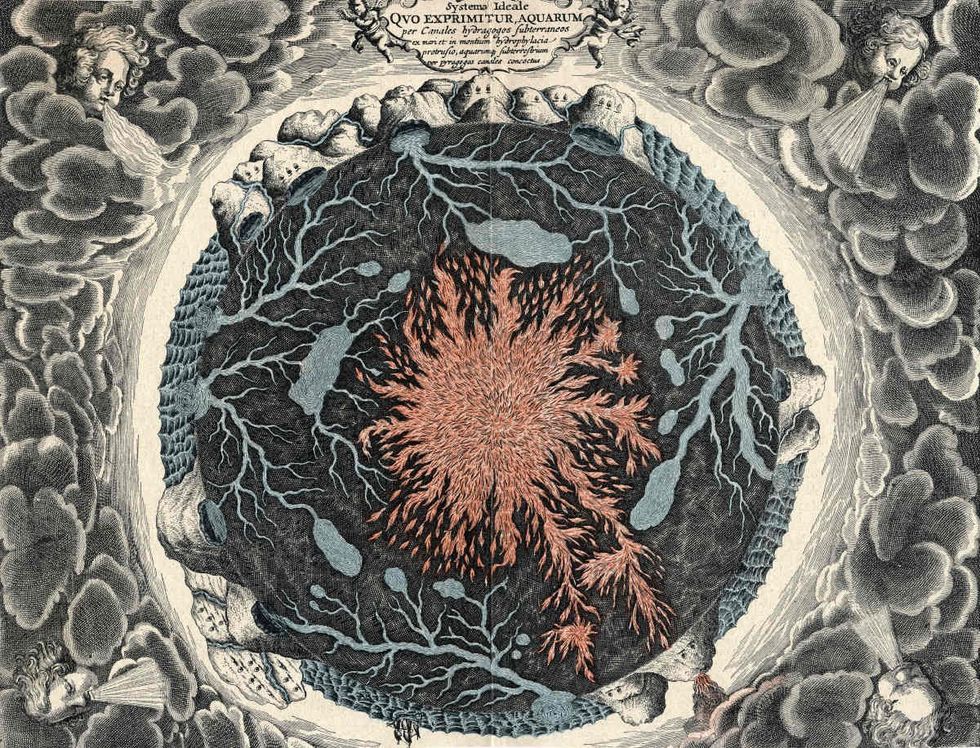

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Hugo Sykes Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Representative Image Source: Sectional view of the Earth, showing central fire and underground canals linked to oceans, 1665. From Mundus Subterraneous by Athanasius Kircher. (Photo by Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images) Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | NASA

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Steve Johnson Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project

Representative Image Source: Pexels | RDNE Stock Project Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Representative Image Source: Pexels | Mali Maeder

Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack Photo: Craig Mack

Photo: Craig Mack