From chimpanzees showing an ability to use words to elephants naming each other, the animal kingdom never ceases to surprise us. In 2010, researchers in Greenland’s Qeqertarsuaq Tunua Bay made an equally fascinating discovery: two Arctic whales engaging in a long-distance interaction. The whales had traveled to feast on the plankton that blooms between January and May, but even when they were far apart, their diving remained in perfect sync, as if they were communicating across the water.

Although scientists couldn’t decipher what the whales were saying, their synchronized behavior led researchers to revisit the "acoustic herd theory," a 53-year-old concept explored in a study set to appear in Physical Review Research.

“At first blush, bowhead whale diving behavior looks pretty chaotic and unpredictable,” explained Evgeny Podolskiy, an environmental scientist at Hokkaido University in Japan, according toHakai Magazine.

However, he and his colleagues noticed that the whales coordinated their diving for hours, only to fall silent without warning, sparking even more questions for researchers from Japan, Greenland, and Denmark.They extracted 144 days of information about diving depth and location from 12 bowhead whales, who were tracked through a satellite. Then they merged the animal behavior data with some complex mathematics to uncover patterns hidden in this data. Using algorithms based on “chaos theory,” they found that the whales depicted certain patterns in communication, diving, and social behavior.

The first behavior they noticed in most whales was a 24-hour diving cycle, in which the whales glided from shallow waters to deeper parts until their appetite for plankton was satisfied. While the team was analyzing more patterns, Podolskiy noticed two whales diving synchronously over a considerably long distance. That’s when he felt perplexed. “This is very, very peculiar underwater behavior,” Podolskiy told Hakai Magazine. “It was very exciting.”

“Without direct observations, such as recordings of the two whales, it isn’t possible to determine that the individuals were exchanging calls,” said researcher Teilmann, in a Hokkaido University press release, “The observed subsurface behavior might be the first evidence supporting the acoustic herd theory of long-range signaling in baleen whales proposed by Payne and Webb back in 1971.” The possibility that two whales can remain acoustically connected even when they are miles apart, is mind-bending.

However, Christopher Clark, a bioacoustics researcher at Cornell University in New York, wasn’t yet sure that this synchronization observed between the two whales was solid proof that could explain the acoustic-connection theory. “It’s operating over a scale that is unobservable to humans,” he said. Hence the synchronization of whales remains a mystery for now. Perhaps the two whales were communicating with each other about plankton or maybe warning each other about human activity. In any case, the fascinating discovery shows that there's still a lot that human beings can learn from nature and other species.

A pair of scissors.

A pair of scissors. A can opener opening a tin can.

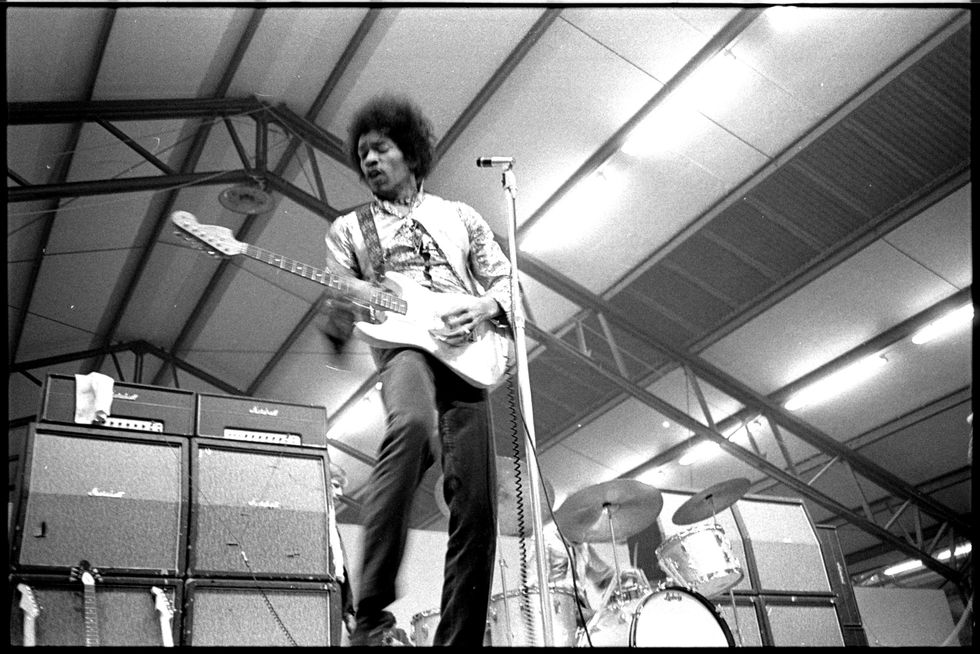

A can opener opening a tin can. Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain

Jimi Hendrix playing on stage.Public Domain A man handing over $20 in cash.

A man handing over $20 in cash. A person using a power saw.

A person using a power saw.

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys

Rock deterioration has damaged some of the inscriptions, but they remain visible. Renan Rodrigues Chandu and Pedro Arcanjo José Feitosa, and the Casa Grande boys The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.

The Serrote do Letreiro site continues to provide rich insights into ancient life.