Egypt's iconic pyramids rise from a rocky plateau in the Sahara Desert, far from any modern water sources—a mystery that has stumped archaeologists for decades. But a new study has uncovered that a long-extinct branch of the Nile once flowed next to these pyramids, offering the answer to how the ancient Egyptians transported the enormous stone blocks needed to build them nearly 4,700 years ago. The study was published in Communications Earth & Environment.

The study was led by Eman Ghoneim, a professor and director of the Space and Drone Remote Sensing Lab at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Born and raised in Egypt, Ghoneim’s curiosity about why the pyramids were built in this remote location led her to apply for National Science Foundation funding to investigate further.

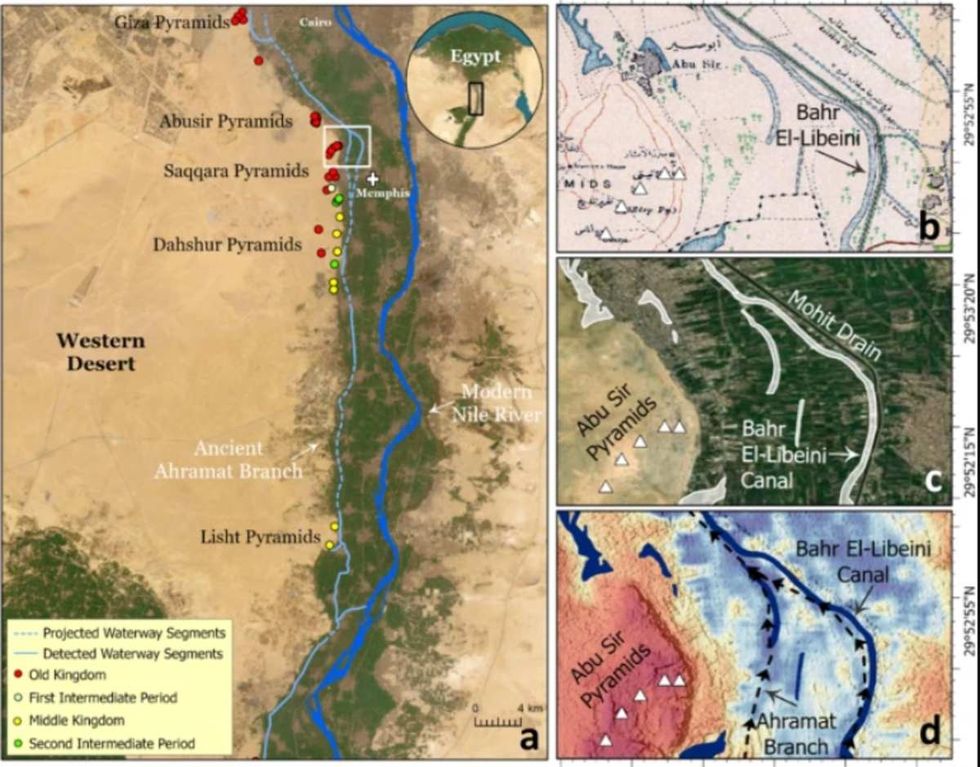

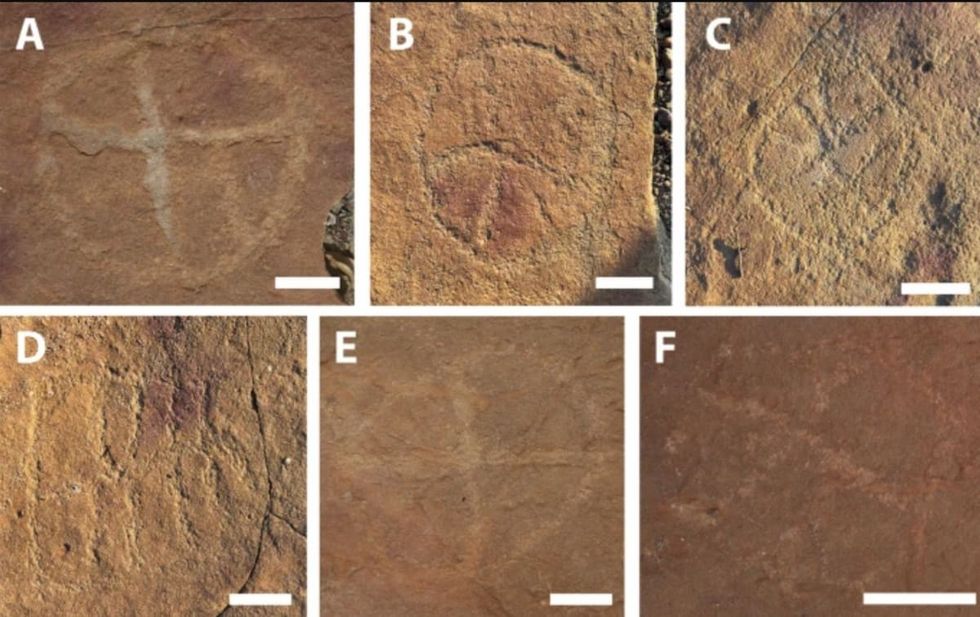

The ground-penetrating radar and electromagnetic tomography of the locale confirmed that it was an ancient branch of the Nile. The team of researchers, led by Ghoneim, mapped a 64-kilometer (40-mile) long, dried-up, branch of the Nile, long buried beneath farmland and desert. They used radar satellite imagery, historical maps, geophysical surveys, and sediment coring for mapping. They extracted two long cores of earth using drilling equipment. The cores revealed sandy sediment consistent with a waterway at a depth of about 25 meters and about 0.5 kilometers wide (one-third of a mile).

“Even though many efforts to reconstruct the early Nile waterways have been conducted, they have largely been confined to soil sample collections from small sites, which has led to the mapping of only fragmented sections of the ancient Nile channel systems,” Ghoneim told CNN. “This is the first study to provide the first map of the long-lost ancient branch of the Nile River.”

The team named this extinct branch of Nile as “Ahramat,” an Arabic word, which means “pyramids” in English. “The large size and extended length of the Ahramat Branch and its proximity to the 31 pyramids in the study area strongly suggests a functional waterway of great importance,” said Ghoneim. She added the possibility that Egyptians would have carried the enormous amounts of construction materials through this channel.

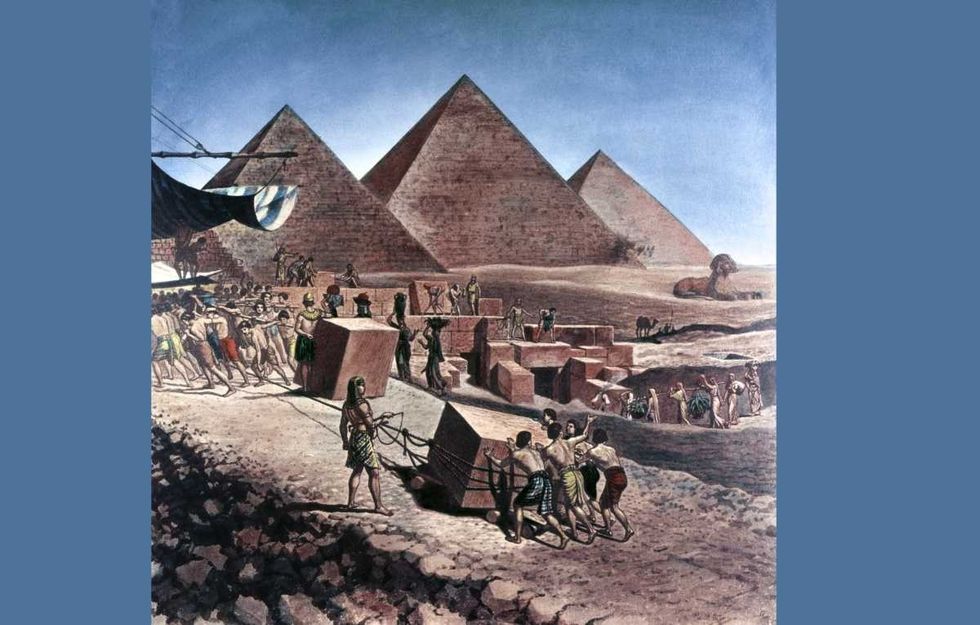

"Locating the actual river branch and having the data that shows there was a waterway that could be used for the transportation of heavier blocks, equipment, people, everything, really helps us explain pyramid construction," Suzanne Onstine, study co-author, told BBC.

The study also related the probability that “countless” temples might still be buried beneath the agricultural fields and desert sands along the riverbank of the Ahramat Branch. This branch could have dried up or vanished most likely due to drought, sandstorm, or desertification, said Ghoneim.

The Nile River has played a key role in the development and expansion of Egyptian civilization. Given the arid landscape, the area depended heavily on the river as a means of sustenance. It would also serve as a key form of transportation. This included the movement of goods and building materials. This was why a majority of the monuments and important buildings were located close to the Nile river and its peripheral branches.

Also speaking to CNN, Nick Marriner, a geographer at the French National Centre for Scientific Research in Paris, said, “The study completes an important part of the past landscape puzzle. By putting together these pieces we can gain a clearer picture of what the Nile floodplain looked like at the time of the pyramid builders and how the ancient Egyptians harnessed their environments to transport building materials for their monumental construction endeavors.” The team believes that deeper research would facilitate archaeological excavations along the Nile's banks and reveal insights into Egyptian cultural heritage.

Editor's note: This article was originally published on July 5, 2024. It has since been updated.

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665

Pictured: The newspaper ad announcing Taco Bell's purchase of the Liberty Bell.Photo credit: @lateralus1665 One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of the later announcements of the fake "Washing of the Lions" events.Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva

This prank went a little too far...Photo credit: Canva The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

The smoky prank that was confused for an actual volcanic eruption.Photo credit: Harold Wahlman

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books.

Packhorse librarians ready to start delivering books. Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia

Pack Horse Library Project - Wikipedia Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Packhorse librarian reading to a man.

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia

Fichier:Uxbridge Center, 1839.png — Wikipédia File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons

File:Women's Political Union of New Jersey.jpg - Wikimedia Commons File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

File:Liliuokalani, photograph by Prince, of Washington (cropped ...

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Theresa Malkiel

commons.wikimedia.org

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

Six Shirtwaist Strike women in 1909

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

U.S. First Lady Jackie Kennedy arriving in Palm Beach | Flickr

Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source:  Image Source:

Image Source: